Nansen Passports

Passports, visas, residence and work permits, and journalists’ overseas accreditations have been a recurring thread in my work for the last few years*—the inevitable result of writing about an American journalist who spent much of her life in Europe. Working her way through bureaucratic red tape to be sure she had the correct permissions to go where she she needed to be was a fact of life for Sigrid Schultz. She took it seriously, even when the home office back in Chicago thought she was being fussy, because she knew border officials in Europe took proper documentation seriously.

In the years between the two world war, when Schultz was active, official identity documents were important. Millions of people were left stateless by a combination of the changes that reshaped the map of Europe, the revolutions and subsequent civil war in Russia, the Armenian genocide in the former Ottoman Empire and the constant small-scale wars between the new states created by the peacemakers in Versailles. Without valid passports, homeless refugees found it almost impossible to find asylum in countries that were already in economic distress due first to the ravages of war and later to the great depression.

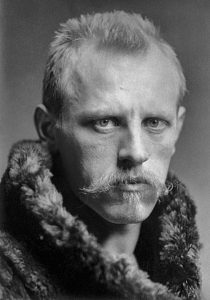

A Norwegian polar explorer turned diplomat named Fridtjof Nansen had successfully organized the repatriation of prisoners of war after World War I. In 1921, the League of Nations named him head of the Office of the High commissioner for Refugees, with a mandate to repatriate the refugees or arrange for them to be distributed between other countries. It soon became clear the many of the refugees couldn’t or wouldn’t return to the countries they had left.

His budget did not allow him to give direct aid to refugees. Instead he proposed a solution that became known as the Nansen passport—a certificate issued by the country in which the homeless had taken refugee that served as both a valid form of identification and a travel permit. The passport did not grant its holders citizenship, but it allowed them them to cross borders in search of work and family members and protected them from deportation.* It was ultimately recognized by 52 countries.

Roughly 450,000 refugees, most of them Russian and Armenian, carried Nansen passports between between 1922 and 1942.

*It also provided governments with a tool for tracking refugees. Identity documents always have a dark side.