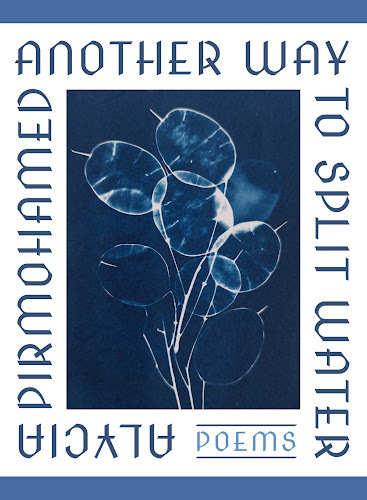

Alycia Pirmohamed, Another Way to Split Water

ORIGIN OF WATER II

as a child she wore a skirt of seagulls

and was afraid of thedark called her mother god

because what else

could mother an ocean butgod? she ate nankhatai

and plaited her hair she smelled of cardamom

newly crushed andboiled she split into spring’s tulips

carried a jar ofcondolences just in case.

she was a daughter caughtpraying in the mountains.

she was stone through stone melodic a vase of trees

rattled by her name:water like the roots that hold

the earth together.

ginan and its wovenstanzas she is the sound of a

messenger calling foranother bird another

metaphor for god as a child how was she to know

what to call beloved?

I’mboth struck and charmed by the slow progressions of lyric observation and philosophicalinquiry throughout “Canadian-born poet based in Scotland” Alycia Pirmohamed’sfull-length poetry debut,

Another Way to Split Water

(Portland OR: YesYesBooks/Edinburgh: Polygon Books, 2022). “I see the wind pull down the tautness /of trees and the swans at the lagoon part / through the wreckage.” she writes,as part of the poem “MEDITATION WHILE PLAITING MY HAIR,” “Each one is anothertranslation for love / if love was more vessel than loose thread.” There issuch a tone and tenor to each word; her craft is obvious, but managed in a waythat simultaneously suggest an ease, even as the poems themselves areconstantly seeking answers, seeking ground, across great distances of uncertaintyand difficulty. “Yes, I desire knowledge,” she writes, as part of “AFTER THEHOUSE OF WISDOM,” “whether physical or moral or spiritual. / This kind oflonging is a pattern embossed / on my skin.” It is these same patterns,perhaps, that stretch out across the page into her lyric, attempting toarticulate what is otherwise unspoken.

I’mboth struck and charmed by the slow progressions of lyric observation and philosophicalinquiry throughout “Canadian-born poet based in Scotland” Alycia Pirmohamed’sfull-length poetry debut,

Another Way to Split Water

(Portland OR: YesYesBooks/Edinburgh: Polygon Books, 2022). “I see the wind pull down the tautness /of trees and the swans at the lagoon part / through the wreckage.” she writes,as part of the poem “MEDITATION WHILE PLAITING MY HAIR,” “Each one is anothertranslation for love / if love was more vessel than loose thread.” There issuch a tone and tenor to each word; her craft is obvious, but managed in a waythat simultaneously suggest an ease, even as the poems themselves areconstantly seeking answers, seeking ground, across great distances of uncertaintyand difficulty. “Yes, I desire knowledge,” she writes, as part of “AFTER THEHOUSE OF WISDOM,” “whether physical or moral or spiritual. / This kind oflonging is a pattern embossed / on my skin.” It is these same patterns,perhaps, that stretch out across the page into her lyric, attempting toarticulate what is otherwise unspoken.Thereis such a strange and haunting beauty to her descriptions, whether through howshe describes “each stammer of lightning” as part of the poem “NIGHTS /FLATLINE,” or, as part of the poem “I WANT THE KIND OF PERMANENCE IN / ABIRDWATCHER’S CATALOGUE,” as she offers: “Any birdwatcher will tell you / that wingedboats // do not howl through their sharp, pyramid beaks. // That sound clickingthrough / waterlogged bodies // must be the prosody of my own desires.” The languageof the poems across Another Way to Split Water delight in sparks andelectrical patterns, providing far more lines and phrases that leap out thanone can keep track of, beyond simply wishing to reproduce the book entirely. “Originsare also small memories,” she writes, as part of the poem “AFTER THE HOUSE OFWISDOM,” “and there is an ethics to remembering— / I hear lilting from belowthe evening green / that houses our episodic ghosts.” Two pages further, thepoem “NERIUM OLEANDER” offers: “How much of her skin / is a body of water? // Nerium/ because she is a flood // of rain as it falls / into a river, // because shesprouts / in rich alluvials.”