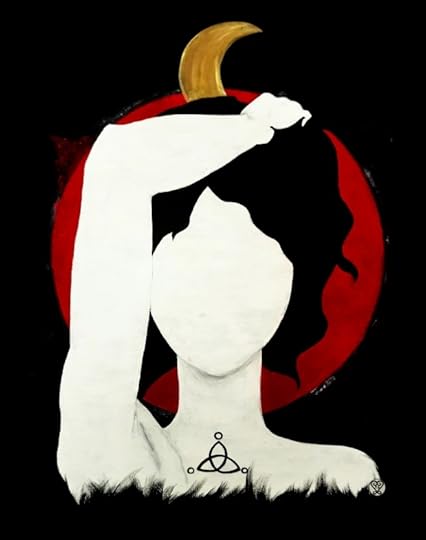

Goddess: Part One – Lilith.

[It’s the end of an era and the start of something new. I’ve been primarily working with goddess archetypes as part of my practice since I was fourteen. Now it seems its time for me to move on. But, in honour of the feminine archetypes that have guided me thus far, this is the goddess series.]

The room is dark, empty, just you, a walnut coffee table and two grey armchairs. There are eight candles on the table, three black, three red, two white, they are the only source of light. They’re placed on the table around a small silver disk, on which there is a small lump of smouldering charcoal. In your hand is a large piece of resin, you place it on the charcoal and take a seat. You begin to see something, something you can’t explain, a small tear in the fabric of reality perhaps. Something begins to break through, a crack of light in the dark, the soft smell of the resin burns and dissolves filling the room. You close your eyes, almost involuntary. They flutter shut like the closing of a Venus flytrap, holding something precious within them, you begin to drift…

I’m seven years old and I’m staying with my grandparents for the second time in my life. By this point I’d already learned to be quiet, to only speak when spoken to, to not ask questions, to do as I’m told. This lesson was instilled in me the first time I stayed with them.

I was five or six, it’s difficult to know exactly, remembering such things has never been of any real importance. Events matter. Events change you. Age? Well, what’s the point of it really? It counts you, that’s it. It was a difficult adjustment to make, this learnt silence, and it’s one I’ve unsuccessfully tried to unlearn since. You see, in my house, so long as I didn’t interrupt the adults, use bad language, or insult someone with no reason, (you had to have a reason) I could say what I wanted and ask anything. My favourite question was “why?”, it still is.

I learned the hard way that my grandfather was very different. There was no such thing as curiosity, if I said something, it had a consequence. If I asked a question he didn’t like, I would be berated, then he would turn on my mother for raising such a terrible child. This was just how things went. She’d accept whatever criticism he gave her, be humbled by it, she’d say she’d do better. She’d take me aside, quietly, and explain to me that I shouldn’t really speak unless spoken to, there are certain freedoms he has that I don’t. I’d be sent to my room, the one that used to be my auntie’s, and I’d hear him, screaming about me. I’d hear my mother apologising for me, my grandmother agreeing with everything he says. I’d fall asleep to it, promising to hold my tongue from that moment on. I’d fail at this several times in my life, but on those nights, I’d mean it. I wondered then, like I do now, if what I had asked was so bad:

“Grandad, why are you always shouting?”

That however, was then, this is now, now, I’m seven, and my mother’s in hospital. My grandparents haven’t spoken to my mother in almost a year. She got back together with my father, and apparently that was something she shouldn’t have done. I have a vague memory of being told we weren’t welcome in their home anymore and my mother, crying by the fridge, whilst I held onto her skirt. But, my mother’s in hospital and this changes things, not the speaking to her part, they’re still not doing that, but my father has disappeared again, and I have nowhere else to go.

At first, I’m sent to stay one street over at my mother’s friend’s house. I’m there two days. Night one was spent with her son in his bed, he’s a month younger than me and he’s sometime-ish with his friendship, he prefers boys. The second night they put me on the sofa in the living room. The third day I’m taken to my grandparent’s house, I assume I did something wrong and they didn’t want me there anymore.

When I get to my grandparents’ house, they argue about who’s going to take me to school the next day. I lie to make things easier for them. I tell them the summer holidays have started, it’s not a big lie, it was only a few days away.

For the rest of my time there I keep my mouth shut and my head down. I write, I draw, I dig holes in the garden pretending I’m an archaeologist. I do as I’m told, I eat strawberries and peas fresh from the garden.

When it gets dark I’m told to “have a wash and get ready for bed”, and to make sure I wear socks. After a week I’m told to “sort myself out, and get ready for bed”, grandad says “have a wash” makes it sound like I’m a farm animal. Grandma agrees and stops using this term. To me, “sort yourself out” sounds strange, but it isn’t my place to say anything, I keep my head down, I do as I’m told… within reason. You see, the very idea of wearing socks to bed is so ridiculous, that if only I was allowed to speak and explain this, they soon would have understood. My argument would have been so convincing, they would’ve had to tell their friends, who would tell their friends, until the whole world understood the elegance of my wisdom: Socks are for outside, when it’s cold. That’s it!

Unfortunately, lacking the ability to speak other than to say: “yes, no, thank you, goodnight.” I had to learn a new talent, being sneaky. It was an ingenious plan; Steven Hawking would have been proud. I’d wear the socks to bed, then wriggle them off once I was tucked in, and just say they came off when I was sleeping. Alternatively, if I woke up a little earlier then them, I’d put the socks back on and pretend they were on the whole time. Nobel Prize winning genius. This plan worked wonders, until one morning I woke up and couldn’t find the socks. I searched that bed inside and out, I searched under the bed, I still have no idea what happened to those socks. The only plausible explanation is that I was abducted by aliens in the middle of the night, the socks got beamed up with me and got stuck in their beaming pipe thing… I don’t know how aliens work.

Morning: after ‘sorting myself out’ and getting dressed, I’d go downstairs and sit on the floor in front of my grandma, so she could comb and plait my hair. This was always an intense experience, grandmothers are vicious creatures by nature, if you didn’t already know. They’re like nuns, it’s as though they’re punishing you for something, but they won’t ever tell you what. The slightest whimper as hair catches in the comb, a whispered “ouch” when my hair is pulled too tight will be met with the sentence: “You have to suffer for your beauty.” Fair enough, okay, makes sense, to a certain degree. Even at seven I overheard enough conversations about cosmetic surgeries, tragic hair bleaching, perm burns, extensions, hot comb panic attacks and breast implants, to get a good enough sense of what it all meant. You have to suffer to be beautiful, women must be beautiful, women have to suffer. Of course, I didn’t think of this then, back then all I had was a vague idea. Women had plastic surgery to look nicer, other women hated that. Plastic surgery looked painful, the ‘other women’ seemed to find that comforting.

So, by the time I was a teenager, and passing out once a month from excruciating period pains, I finally, fully understood the lesson one woman was imparting to another. Your life is going to be one of quiet suffering, because you, young lady, were born wrong. If you wanted to be something, if you wanted to matter, if you wanted to be heard, you should have been born male. Think of all the freedom you could have had if you were a boy, think of all the friends, everyone would want to know you, you would even be allowed to speak.

Lilith: That got kind of deep and personal, I’m not sure what the point was to any of it, could you explain? (She licks her lips and sits down in the chair opposite me. Her red dress matches her pout and hitches up around her thighs as she crosses her legs.)

Me: Umm, I guess I’ll try. Umm… well, maybe I brought this up because I feel stuck most of the time. I’m stuck in my body and the limitations that come with it. Even this is a limitation, speaking to you and not to someone solid and real. Being female is a limitation for me, beauty is a limitation and I’ve grown up in a society where females should be beautiful.

In university I wrote my dissertation on beauty and why women must suffer for it, and because of it. I was reading Seven Days in the Art World (2008) by Sarah Thornton at the time, don’t know why that’s relevant, but it’s something I remember, and my favourite question kept circling around the inside of my head, WHY? Maybe it was because I was supposed to be ‘beautiful’, I’m female and that’s the most endearing quality you can have if you’re female, but I had never felt ‘beautiful’. My skin was the wrong colour, I was too short and awkward, and my hair didn’t look like the black women I saw on TV.

Lilith: The black women on TV all had weaves.

Me: A fact I know now but didn’t at the time. I just thought they all had nice hair and I didn’t, and there was no one on TV that I could identify with, except Lisa Bonnet. I’m still a little annoyed that Jason Momoa married her, cool should not marry cool, it’s not fair on the universe. But still, I was nothing like Lisa Bonnet either, I was still too short, and my hair was still nothing like hers. I still hate my hair by the way, I just hate it. The only times I’ve been truly comfortable with my hair is when I was a teenager and had extensions and a few years back when I shaved my head.

Lilith: Why don’t you shave your head again? Simple.

Me: The obvious reason. Maintenance, I’m lazy.

So, to be beautiful, to be like Lisa Bonnet, I would have to suffer for it, and my question was: WHY? Was there some cultural reason, historical, religious or just a fact of the universe? My question led to my dissertation question: ‘Have concepts of beauty led to the demonization and punishment of women?” I spent the next year fascinated by the idea of beauty. I wanted to know if there was room for perfection in beauty? Or if the body had to be imperfect to be beautiful? If so what did that say about the modern standards of beauty? I learned that beauty was a dirty word because it’s subjective, its fluid, it’s too open to interpretation from too many angles. I learned that beauty is like art, entirely selfish. But I’m skipping ahead.

During my research I came across Connie Imboden, whose photographs of the human form reminded me of these mini sculptures I was making at the time called ‘See Me, Feel Me’. Her work led, in a roundabout way to Marc Quinn, or a return to Marc Quinn would be more accurate.

The first time I came across Marc Quinn was such a long time ago I can’t even remember the date. It was when ‘Self’ was being exhibited in the Saatchi Gallery, so, that long ago. I remember it reminding me of the statues of ancient Greek gods and goddesses, sort of solid and permanent but then saying that, also highly dependent on its refrigeration equipment like a life support machine. I later saw his 2001 marble sculpture ‘Kiss’ at the Bristol Museum, and I’ve seen pictures of his others. The sculptures are made from Macedonian marble, this white soft stone which is said to provide a sense of perfection. The fact that he uses white marble for his sculptures also reminds me of this idea of the neutral body, that these sculptures can be anyone. It reminded me of the feminist writer D. Haraway who said: “The ‘neutral’ body was always unmarked, white and masculine.” I thought Quinn had taken the idea of the neutral body and bastardised it by making it female, or disabled or whatever else he felt like doing. He was questioning what made something beautiful, and he was right to do so, we needed it, I needed it.

I found the idea of the neutral body enticing. It’s designed to be anyone, but the beauty of the neutral body seems more alienating than classical, it feels more like a statement than something that has ‘neutral’ in its name. The neutral body has always felt more like an ideal, white and masculine, iconic and perfect.

Lilith: Do you think this means that to write something or even create something that would be considered ‘neutral’, beautiful and accessible to all, your characters should be white and male. To make this more accessible, for example, I should be white and male? (Her eyes tease me; her lips fall into a half smirk.)

Me: I know that these things depend on what audience you’re writing for, but yes. Though I’m getting off point again.

In the Waterstone’s in Bristol, there is a little section, consisting of two short stacks called ‘Black Writer’s’. I don’t want anything I write to ever be in that section, I don’t want my writing to be segregated, to be deemed as some great feat. It seems to me, that what is meant to be a celebration of black writers can also be a limitation for us. If black writers were truly equal, they wouldn’t be celebrated. It’s like ‘Look at them, they’ve overcome their blackness and strung intelligible sentences together.’

Chick-lit as well, that’s an offensive term. I don’t want anything I write to be labelled chick-lit. ‘Look, women can write, but only for other women.’

So, my point, cultural, historical, religious? I wanted to know why I’d been taught to hate myself. Why had I watched women teach their daughters to hate themselves? And why am I still watching new mums teach their daughters to hate themselves? Why?

Lilith: I’m curious myself. (Is that anger I see, a flurry of fury raging behind those deep chocolate eyes?)