Our Story-Telling Minds (with Mini Grey)

(…and how theyget us into trouble…)

Books. They are abrilliant technology. Simple, portable, easy to mend. And they give us humans atotal superpower compared to all the other animals: a superpower of collected minds, empathy and time-travel.

(Books arealso dangerous and powerful: all tyrannical despots know this and set fire tothem, as do angry mobs.)

Angry mob

Angry mobThe power thatbooks give us is of building on everyone’s ideas that have ever been writtendown, and being able to grow our culture, knowledge and science. Before thebooks, there were the stories, and to remember stuff, we remembered throughstory.

By Jan Pienkowski

By Jan PienkowskiThe MemoryPalace is an example of using story for remembering. You imagine a journeyaround a location you know well – maybe your own house. Then to memorise a list,eg of shopping, – you imagine each item in a location along your journey, butmake the image memorable. (There’s a guide here )

By Tom Gauld, from You're All Jealous of My Jetpack

By Tom Gauld, from You're All Jealous of My JetpackOur minds are wiredfor story-telling. The brain is a story-addict. And why? Our instinct for storyis a survival skill. In a prehistoric world full of fangs and tusks and claws,narrative kept us soft-skinned small-toothed weak-bodied humans alive. We mighthave been soft and feeble-bodied (compared to a sabre-toothed Smilodon) but us humans hadimagination and co-operation, and this is where story comes in. To get youridea to persist and endure from person to person it needs to grip theimagination and stick in the mind and that’s what stories do – maybe throughthe empathy that binds us up with the central character and invests us in how thestory unfolds..

Painting from the Cueva de las Manos

Painting from the Cueva de las ManosYou can watch yourstorytelling mind in action using words and pictures.

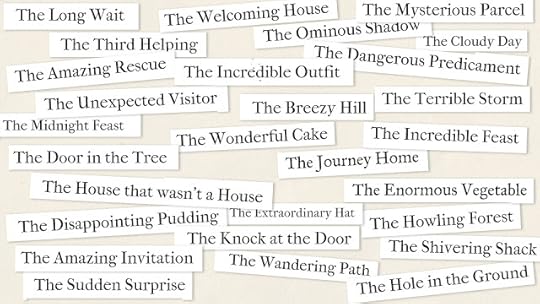

Here are some objects.

And here are somecaptions.

Put a caption witha word, and see what your story-telling mind produces:

Now we do this and change the picture:

What did your mind make? Try again with new words and pictures:

..and then swap the picture...

..and then swap the picture...

What did your mind make this time?

If we put pictures in asequence – a story happens. We can't help linking those pictures together.

Picture sequence by Blexbolex from Romance/Ballad. You can see more here.

Picture sequence by Blexbolex from Romance/Ballad. You can see more here. Our minds areconstantly trying to build the story, to make the meaning, to understand what’shappening.

But that means weinvest agency where often there isn’t. We constantly attribute meaning and purposewhere maybe there isn’t. That rustle in the grass could be a tiger…butit could just be the wind. Evolutionarily, the safer strategy is to be overfearful and suspect it's the tiger - because in the unlikely event it IS the tiger, the penalty is death; whereas being overly fearful of wind doesn't have a huge penalty. But from there comesfear and superstition. I can’t help attributing luckiness to some of my socks,and I’ve heard of footballers who’ve had to have their lucky pants flown out tothem when they’ve been forgotten. The supernatural and the uncanny are neverfar away...

From There's a Ghost in This House by Oliver Jeffers

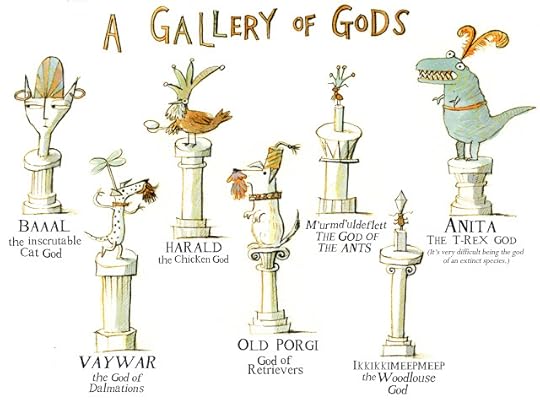

From There's a Ghost in This House by Oliver JeffersBut then also withthe narrative comes the Happy Ending, which is the only satisfactory way to end your own story. Eternal life in another world seems to be amuch more reasonable ending to life on Earth than non-existence. So Gods become anessential invention.

A compelling story will transport you - deliciously - into a story world. It uses our empathy to produce an emotional response - strong feelings - plus it makes things memorable.

These things thatmake story-telling so powerful: transportation, emotional response, improvedrecall – can be misused. Stories can be used to really effectively spreadmisinformation – and so we get to conspiracy theories and propaganda that haveall the trademark story ‘stickiness’ in the human brain.

Engraving by Gustave Dore

Engraving by Gustave DoreLately at ourhouse we’ve been trying out ChatGPT.

In its own description, ChatGPT is “an AI-poweredchatbot developed by OpenAI, based on the GPT (Generative PretrainedTransformer) language model. It uses deep learning techniques to generatehuman-like responses to text inputs in a conversational manner.”

Well, it turns out to be really rather goodat inventing stories. This is what happened when my partner Tony tried to get it to write a story about me:

Tony: Can you tell me a short story aboutMini Grey in the style of Jeeves and Wooster?

ChatGPT: I'm afraid I cannot provide a short storyabout Mini Grey in the style of Jeeves and Wooster, as they are characterscreated by P.G. Wodehouse, and Mini Grey is a real-life children's author andillustrator. However, I can provide a short story in the style of Jeeves andWooster if you would like.

Tony: Yes please!

ChatGPT: Certainly, sir/madam. Here is a short story inthe style of Jeeves and Wooster:

It was a fine morning at the Drones Club, and BertramWooster, that well-known man-about-town, was enjoying a spot of breakfast withhis good friend and fellow member, Bingo Little.

"Jeeves has been suggesting that I read morebooks, you know," remarked Bingo, buttering his toast with an air ofnonchalance.

"Books, eh? What sort of books, old man?"inquired Bertie.

"Oh, you know, the classics and suchlike. Hementioned one by a certain Mini Grey that he thought might be ofinterest."

"Mini Grey? Sounds like a chap you might bump intoat the club, what? But if Jeeves recommends it, I suppose it must be worth alook."

And so, Bertie procured a copy of Mini Grey's latesttome and settled down to read it in the comfort of his bachelor flat.

To his surprise, he found himself thoroughly engrossedin the tale of a plucky little girl named Traction Man, and his adventures withhis trusty sidekick, Scrubbing Brush.

"Why, this is jolly good stuff, Bingo!"exclaimed Bertie, upon their next meeting at the club. "I never thoughtI'd be one for children's books, but this Mini Grey is a real corker."

Bingo nodded sagely. "I say, Jeeves always knowsbest, doesn't he? Perhaps he ought to take up a spot of literary criticism inhis spare time."

"Quite so, old bean. One can never have too manybooks to peruse, what?" And with that, the two chums raised their glassesin a toast to the joys of reading and the impeccable taste of their personalgentleman's gentleman.

I was pretty impressed by ChatGPT's Wodehouse effort, on the whole. For a Bot that is basically predicting the next word, it's managing to create something convincingly storylike. In a content-hungry, story-hungry world it may find itself very busy.

So watch out for stories – they can lead us astray….tofear wolves, to equate the beautiful with the good, and the ugly with the evil,to expect a happy ending and to exist forever, to believe what we feel is right rather than question our assumptions.

(And don’t get me started about story-book farms….)

But there’s anotherpicture book illusion that happens because of the stories we tell ourselves, and it goes like this:

The icebergillusion

When you see a published picture book, you are lookingat an iceberg of Hard Work, and lots of it you cannot see. With the iceberg 80% is invisible and lurking below the water’ssurface. Hiding there are all the other things it has been and the work thatwas wrong, the many versions in drawers that didn’t work, the ideas that had tobe cut or abandoned, the rethinking and sweat and struggle. Just as in a magictrick, we don’t see all the practice that went into making it look effortless.So sometimes it seems obvious to assume it was easy andeffortless to make - which means that if you're struggling, that is unusual andit is because you are not somehow talented enough. But you are being sold anillusion.

Struggler, you are not alone.

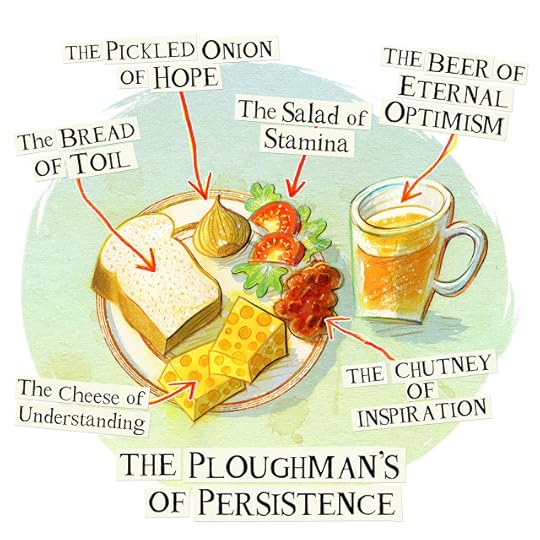

So, to finish, for strugglers everywhere,here is the Ploughman’s of Persistence.

You just have to put more work into making that thingthan you ever expected.

Mini’s latest book is The Greatest Show on Earth, published by Puffin.