Little Mr. Prose Poem: Selected Poems of Russell Edson, ed. Craig Morgan Teicher

Edson was one of thedefinitive practitioners of the contemporary American prose poem. Charles Simic,in his beautiful Foreword, says that no one has yet offered a convincingdefinition of prose poetry. Nonetheless, permit me to make an attempt. Is aprose poem just a poem with no line breaks? If so, what can prose sentences andparagraphs do for a poem that lines can’t? What is prose and what is poetry,and what are the supposed differences between them? The poet, critic, andtranslator Richard Howard, who was my graduate school mentor and friend, has awonderfully useful and precise maxim for describing the difference between poetryand prose: “verse reverses, prose proceeds.”

This concise and musicalphrase summarizes what I believe to be one of the central truths about thenature of these two forms of writing: though made of the same basic stuff—letters,words, punctuation—once they take their shapes, they are actually differentsubstances, like water and oil (though they do mix), or, perhaps, more likewater and wood. They are composed of the same elements, but those elements aredeployed so differently that the results can seem like distant cousins at best.

But what are they? First,we need a definition of “prose”: it’s the word on the street; the writingpeople talk in; the words on signs; and the stuff, beside images, that the Internetis made of. In itself, it’s not scary (though lots of it piled up, say, in abig, fat book, might be). Reading prose, you might not even realize you’rereading it. (“‘No, And’: Russell Edson’s Poetry of Contradiction,” Craig MorganTeicher)

Yearsago I read an essay by American poet Sarah Manguso on the prose poems of Connecticut poet Russell Edson (1935-2014); despite usually believing and following whateverManguso might say about anything, I was never convinced by the work of Russell Edson, said to be the father of the American prose poem. I even picked up acopy of his prior selected a few years back, The Tunnel: Selected Poems of Russell Edson (Oberlin College Press, 1994), but couldn’t figure my way. I couldn’thear music in his poems, feeling them closer to incomplete short stories thanto the electric possibilities of the prose poem, especially against poets suchas Rosmarie Waldrop, Lisa Jarnot, Lisa Robertson, Robert Kroetsch, Anne Carsonand others. How was Edson’s work so praised?

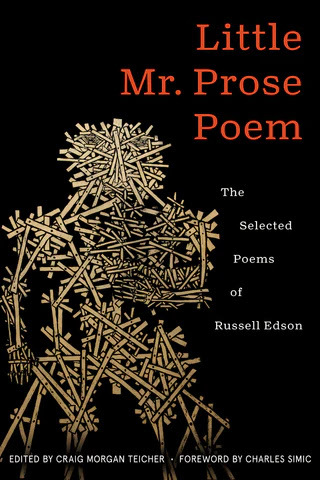

Yearsago I read an essay by American poet Sarah Manguso on the prose poems of Connecticut poet Russell Edson (1935-2014); despite usually believing and following whateverManguso might say about anything, I was never convinced by the work of Russell Edson, said to be the father of the American prose poem. I even picked up acopy of his prior selected a few years back, The Tunnel: Selected Poems of Russell Edson (Oberlin College Press, 1994), but couldn’t figure my way. I couldn’thear music in his poems, feeling them closer to incomplete short stories thanto the electric possibilities of the prose poem, especially against poets suchas Rosmarie Waldrop, Lisa Jarnot, Lisa Robertson, Robert Kroetsch, Anne Carsonand others. How was Edson’s work so praised? Soof course, I was curious to see a copy of Little Mr. Prose Poem: Selected Poemsof Russell Edson, ed. Craig Morgan Teicher, with a Foreword by Charles Simic (Rochester NY: BOA Editions, 2023) land in my mailbox recently; perhapsthis collection might provide some sense of what it is I’d been missing, or atleast, not getting? Perhaps it is as simple as requiring the correct entrypoint in my reading. In my late twenties, after hearing from a variety of writersaround me on the brilliance of the work of Toronto poet David McFadden, thehalf-dozen titles I encountered weren’t providing me with any answers as to why,until I picked up a copy of his Governor General’s Award-shortlisted The Artof Darkness (McClelland and Stewart, 1984), a book that became my personalRosetta Stone for the since-late McFadden’s fifty years of publishing. With thatone title, all, including his brilliance, became abundantly and absolutely clear.

AsCharles Simic offers in his introduction: “Edson said that he wanted to write withoutdebt or obligation to any literary form or idea. What made him fond of prosepoetry, he claimed, is its awkwardness and its seeming lack of ambition. Themonster children of two incompatible strategies, the lyric and the narrative,they are playful and irreverent.” Little Mr. Prose Poem selects piecesfrom ten different collections produced during Edson’s life: The Very Thing ThatHappens (New Directions, 1964), What A Man Can See (The Jargon Society,1969), The Childhood of an Equestrian (Harper and Row, 1973), The ClamTheater (Wesleyan University Press, 1973), The Intuitive Journey (Harperand Row, 1976), The Reason Why the Closet Man Is Never Sad (WesleyanUniversity Press, 1977), The Wounded Breakfast (Wesleyan UniversityPress, 1985), The Tormented Mirror (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2001),The Rooster’s Wife (BOA Editions, 2005) and See Jack (Universityof Pittsburgh Press, 2009). Given the final collection on this particular listemerged five years prior to the author’s death, one is left to wonder if therewere uncollected pieces or even an unfinished manuscript left behind after hedied? Did all of his pieces fall within the boundaries of his published books?

Thereare ways that Edson’s odd narratives, populated with fragments and layerings ofscenes and characters, feel akin to musings, constructed as narrativeaccumulations across the structure of the prose poem. And yet, there are times Iwonder how these are “prose poems” instead of being called, perhaps, “postcardfictions” or “flash fictions.” It would appear that an important element of Edson’sform is the way the narrratives turn between sentences: his sentencesaccumulate, but don’t necessarily form a straight line. There are elements ofthe surreal, but Edson is no surrealist; instead, he seems a realist who blurs andlayers his statements up against the impossible. I might not be able to hear aparticular music through Edson’s lines, but there certainly is a patterning; alayering, of image and idea, of narrative overlay, offering moments of introspectionas the poems throughout the collection become larger, more complex. As well,Edson’s poems seem to favour the ellipses, offering multiple openings butoffering no straightforward conclusions, easy or otherwise. Not a surrealist,but a poet who offers occasional deflections of narrative. Even a deflection isan acknowledgment of the real, as a shape drawn around an absence. A deflection,or an array of characters who might not necessarily be properly payingattention, or speaking the truth of the story, as the poem “Baby Pianos,” from TheTormented Mirror, begins:

A piano had made a huge manure. Its handler hoped thelady of the house wouldn’t notice.

But the ladyof the house said, what is that huge darkness?

The piano justhad a baby, said the handler.

But I don’t seeany keys, said the lady of the house. They come later, like baby teeth, saidthe handler.

Meanwhile thepiano had dropped another huge manure.

AsCraig Morgan Teicher writes as part of his afterword that Edson is “obsessedwith miscommunication; it is his bedrock truth. People don’t listen to eachother, are generally intent on fulfilling their own needs, and willfullyignorant of the needs of those around them. His characters constantly argue andcontradict one another.” Moving through this collection, I can now see Edson’sinfluence in a variety of younger American poets, most overtly through Chicago poet Benjamin Niespodziany (who I do think is doing some great things), butalso through Evan Williams, Shane Kowalski, Zachary Schomburg, Leigh Chadwick and the late Noah Eli Gordon, as well asthrough Manguso herself, across those early poetry collections. In many ways,Niespodziany might even be the closest to an inheritor I’ve seen of Edson’swriting, although with the added element of a more overt surrealism viaCanadian poet Stuart Ross. And perhaps, through Little Mr. Prose Poem, Iam slowly beginning to understand what all the fuss has been about.