“X” isn’t a game!

I called this out as one of the trends I saw at GDC. Last year, people were saying that Farmville was not a game, and I argued that it was. This year, I wrote about narrative not being a mechanic and had to extend my comments on it because of the controversy, and Tadhg Kelly bluntly said “Dear Esther is not a game.” At GDC, the rant session featured Manveer Heir saying that it was arrogant and exclusionary not to consider it a game, and arguing that the boundaries of “game” needed to be large and porous. Immediately after, Frank Lantz gave his own rant, which used sports extensively as examples of games.

The definition of game that most people — and I am particularly thinking here of the layman’s use of the term — is basically something like “a form of play which has rules and a goal.” Lots of practitioners and academics have tried pinning it down further. I’ve offered up my own in the past:

Playing a game is the act of solving statistically varied challenge situations presented by an opponent who may or may not be algorithmic within a framework that is a defined systemic model.

Some see this as a “fundamentalist” approach to the definition. But I use it precisely because it is inclusive. It admits of me turning a toy into a game by imposing my own challenge on it (such as a ball being a toy, but trying to catch it after bouncing it against the wall becoming a game with simple rules that I myself define). It admits of sports. It admits of those who turn interpersonal relationships, or the stock market, or anything else, into “a game.”

Some see this as a “fundamentalist” approach to the definition. But I use it precisely because it is inclusive. It admits of me turning a toy into a game by imposing my own challenge on it (such as a ball being a toy, but trying to catch it after bouncing it against the wall becoming a game with simple rules that I myself define). It admits of sports. It admits of those who turn interpersonal relationships, or the stock market, or anything else, into “a game.”

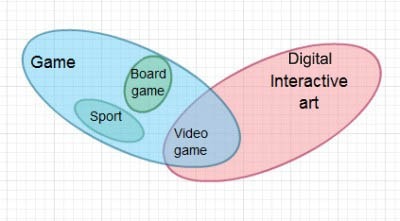

Basically, I see this whole issue as this Venn diagram. I group sports, boardgames, and yes, videogames under “game” because all of them are susceptible to being broken down and analyzed with game grammar. They all have rules. They all have an “opponent” that presents varied challenges to the player. They all have a feedback loop. They all present verbs to the player. They all present goals. The fact that some use real-world physics as the opponent, some use the human body, some use dice or boards, and some use a computer is not even relevant when you break down the game atoms. I can group these easily because I’ve dug into them so much that I know there is something there in common.

That isn’t to say it isn’t a very wide net — I wrote about games that fall on the boundary and seem lacking in goals altogether years ago, and still lumped them under game.

This doesn’t mean I dislike all the huge potential that is in the other side of the diagram. On the contrary — Andean Bird began over on that side, and arguably was more successful there than as a game. And anyone who has followed what I’ve written over the last fifteen years knows that I believe that games can be art.

The question is whether that entire red area should have the name “videogame,” which is what some are advocating. And I am resistant to that, in part because I suspect a Powerpoint slide deck could live over there. The unifying factor seems to simply be “displayed on a computer” to me. Mind you, I have great sympathy for the notion that a digital platform enables great new things for art! On the other hand, I also know that computers are not solely electronic, so even that boundary line feels a bit awkward.

So we could call all that stuff “game.” Or alternatively, we need a name for what Dear Esther is, and that seems to me a simpler problem than renaming the category that encompasses baseball and tiddlywinks, which have both been called games for a very long time.

That said, I don’t see any reason why that should be regarded as dismissive, exclusionary, or derogatory. Videogame designers have been crosspollinating with digital artists for a loooong time now — I think for example of Zach Simpson’s work — and I think that the game developer community is certainly welcoming enough to things that live at the boundaries of either game or interactive art.

In short – there’s no reason to call each other names. But naming things is still a valuable exercise, and I’d hate to lose precision on something that we are finally able to pin down.