Insights into China (Part 1/3): A walk down the street

Whoever gets there first

It’s your first day in a Chinese city. After checking into your hotel you decide to scope out the territory on foot. Disoriented from lack of sleep on the long flight, you smack right into a woman walking ahead of you who inexplicably stops in her tracks while looking at her cellphone. You apologize and she ignores you. You proceed but you can’t walk around her because the couple walking toward you don’t give way. You can’t walk around her other side because there’s a slow walker rearing up and not enough space to squeeze around him either. Momentarily trapped, you manage to wiggle your way past these obstacles and are home-free. But only for a moment, as you close in on a solitary pedestrian walking ahead who manages to take up the entire sidewalk — not because he’s large but because he has eyes in the back of his head. He prevents you from overtaking him by veering in front of you as you try to slip by him on the right and then again when you try to slip by him on the left. Now barreling toward both of you is an electric cyclist. You are forced off the pavement. As you jump onto the street, a car pulls up, forcing you back onto the pavement. The driver doesn’t even slow down! Now three people approach who are about to collide with you and the two pedestrians walking next to you. You get out of the way and place yourself flush against the wall along the other side of the pavement. They flow right through each other like ghosts.

How do they do it? And why doesn’t anyone get upset at this brazen buffeting from all sides? Everyone seems to be walking slowly, dreamlike, ambling at a leisurely pace as if not going anywhere in particular. Yet they are all getting on splendidly. The man with the rear-facing antennae, the woman with the cellphone are long gone. If you suspect the Chinese have a different conception of personal space, you are correct.

A Beijing street

A Beijing streetYou try to understand it from a North American perspective, where people keep a certain distance from each other in public. It’s as if we are all wearing invisible 19th-century hoop skirts that keep people from trespassing on one another’s personal borders. After years of living in China, I once returned to the US and had forgotten about these niceties. I was standing at a street corner waiting for a right-turning car to pass so I could cross the street. My posture that signaled I was about to cross when the driver stopped and started yelling at me. I wasn’t even close to making physical contact with her vehicle but was leaning forward a bit too much for her liking. Although a mere pedestrian, I had violated her territory.

In China, this would not be a problem. You could lean into a car as it slides past, or better yet weasel your way in front of it and make it yield to you. The driver might be mildly annoyed as he’s forced to wait for you and a whole string of pedestrians — now that you’ve opened up a path — to cross the street. It’s often the only way pedestrians can ever get across the street. But he would hardly be ruffled (accidents are a different matter, as we’ll see below). Similarly, as a pedestrian you could walk down the street more insistently, pushing past and squeezing through people as needed, precisely as they do to you (within limits of course: it’s not football or rugby). And despite all this seeming rudeness, nobody gets angry. It’s just the way it’s done, and they all do it that way.

For the freedom to jostle one another, the Chinese agree not to get upset (though “agree” isn’t the right word; it’s cultural and thus unconscious). This is different from say, Japan, where people also get very close to each other but gracefully manage this without physical contact. The Japanese are acutely aware of each other’s presence, and this extends 360 degrees. They also have antennae in the back of their head, with the difference that they are hyper-considerate and step out of the way to let you overtake them, whereas the Chinese intentionally seem to throw obstacles in your path, as if you are in some kind of a race they can’t afford to lose.

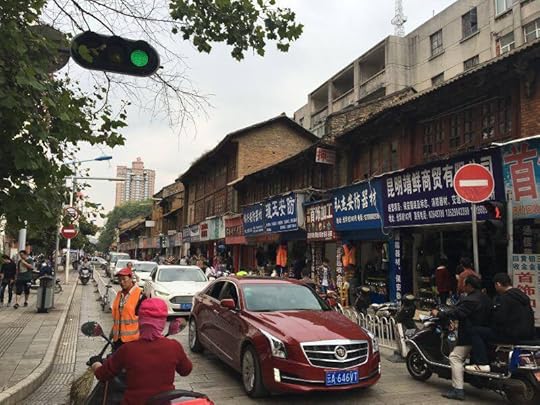

A Kunming street

A Kunming streetIt took a few years of living in the country to understand that the Chinese are not out to stymie you. They don’t in fact have antennae in the back of their head because the truth is, they aren’t even aware of you. That applies to foreigners as much as to themselves. Now, this was not always the case. Back in the 1980s, so much as step out onto the street and a crowd would immediately form around you like a magnet and follow you everywhere, stunned expressions on their faces. In the ’90s, foreigners were becoming boring; you were still stared at but from a distance. Today, in cities with at least a handful of foreign residents or tourists, you are no longer stared at. It’s a great feeling finally to be able to blend in with the locals. But you are now treated like a local.

To have a conception of personal space, you also need a conception of “public space”: how to defer to others occupying the same space, as is everyone’s right. I may be putting it starkly, but the Chinese have no concept of public space. It’s just space, and it’s automatically one’s personal space. Public space is a vacuum that one occupies until forced off it. It’s why people will step right in front of you, blocking your way even when they can clearly see you coming. And they then have the nerve to avoid eye contact and pretend they didn’t see you! But again, that’s not what’s happening. No thought processes are involved. If they do make eye contact, they’ll be perplexed as to why you’re glaring at them. They are not trying to confound you; your feelings couldn’t be farther from their thoughts. Rather, they got there first. The obverse of this is that people don’t mind terribly being forced off their space; they simply occupy the next available space. No one is laying down boundary markers with chalk to claim their private territory wherever they like. They are just getting on without thinking much about it, like water finding the easiest path. This may involve a certain amount of gentle prodding and pushing. When this happens to you, don’t get upset but just move around them.

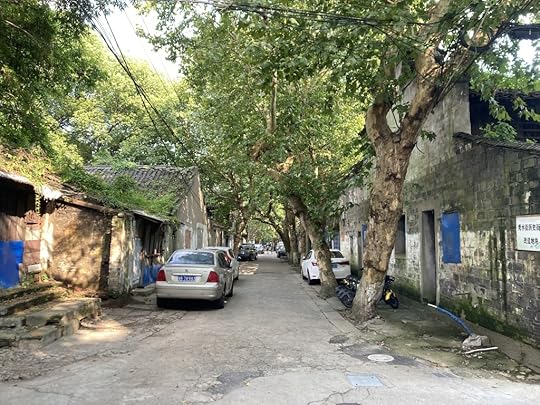

Old neighborhood in Ningbo (soon to be razed)

Old neighborhood in Ningbo (soon to be razed)A very different conception of public space than the rest of us are accustomed to, to be sure, but the system works perfectly well on its own terms. A warning, however. While standing in line somewhere, you may find yourself being jabbed from behind by an old lady’s cane or forearm when failing to keep pace with those in front of you. She may keep nudging you in any case, as if it would get the whole line to move faster. But do not do this with a female if you are a male, especially if her boyfriend or husband is with her. As with anywhere, there are limits it’s good to know about.

Cars on the sidewalk

The Chinese ride bicycles pretty much the same way they walk. Which is to say the only rule of the road is: whoever gets there first. As bicycles can be hazardous to pedestrians and there used to be millions of them, dedicated bike lanes were in general use right up until the turn of the century, when private car ownership took off. As expected, people drove cars the way they rode bicycles. Problems started occurring, compounded by 1) the ease with which one could obtain a driver’s license without having to undergo driver training (you simply paid someone off), and 2) the tendency to ignore traffic lights and the pell-mell that resulted. Regretfully, we didn’t have cellphones back then with cameras, and I lost the opportunity on numerous occasions to document the hilarious spectacle of the Chinese traffic jam of the early 2000s.

Street in Shanghai’s former walled city

Street in Shanghai’s former walled cityYou might expect that if drivers disobeyed the rules of the road, they would be flying into each other left and right. Accidents in those years were indeed frequent, but people did make efforts not to total several years’ worth of their salary. What actually happened was everything ground to a halt. Never did I feel more empowered as a cyclist, zipping past all those blaring horns unable to extricate themselves from the massive logjam. It took some years for the majority to have their collective eureka moment, namely that obeying traffic signals would enable them to get to their destination faster. Reluctantly, drivers started stopping at red lights. Holdouts who couldn’t bring themselves to cooperate resorted to escape routes, driving into oncoming lanes, driving down bike lanes and even on sidewalks, honking cyclists and pedestrians out of the way when they weren’t running the red, which even today is often treated the way we treat the yellow (look both ways when crossing streets in China!). Businessmen chauffered in their Benzs and Bentleys and government officials in their black Audis were particularly fond of scattering the hoi polloi. These class distinctions were blatant and shameless: the more luxurious your car, the greater your right to occupy asphalt and everyone else be damned.

Up until about a decade ago you could still witness another fascinating phenomenon, a form of street theater known as the traffic altercation. The parties involved could not just accept what happened and work out legal matters. They had to come out on top, with all manner of posturing, pointing, and yelling, and they made damn sure everyone witnessed the performance. Once the police arrived, they would negotiate, bargain, even argue with the cops — all without fear of getting shot. Once I was riding my bike to work when I was halted at a busy Beijing intersection by one such scene. Two waidiren (migrant-laborer) couples on mopeds had collided and were blaming each other. The two men were flailing at each other and the two women were trying to tear each other’s shirts off. The big crowd of onlookers surrounding them occupied the entirety of the street and the traffic was frozen. I noticed that one of the immobilized vehicles was a bus full of dumbfounded elderly Caucasian tourists — probably the most interesting sight on their trip!

A Shanghai street

A Shanghai streetIn the years since, drivers have become more civilized and cooperative. But we still see class distinctions operating in the way main roads and thoroughfares are built, privileging the tier of the population that can afford a car. To accommodate car owners, streets are growing in width. They are sometimes so wide that not just the elderly but anyone walking at a normal pace can’t get all the way across before the light turns red. Some boulevards accordingly build a pedestrian island with a second light timed to turn green after the first. Other cities outlaw bicycles on many roads, where widening the road is impractical, freeing up lanes for cars (as in Shanghai with its large burden of historic property). Whereas many cities around the world are turning more bike and pedestrian-friendly, the opposite trend holds sway in China.

China also lags behind when it comes to car accidents. I don’t mean the incidence of accidents, which is comparable to the rest of the world, but people’s behavior. As in fleeing the scene of an accident. It used to be quite common — or worse: intentionally killing a pedestrian who’s been struck by a car. Why in the world would anyone do that? Because the punitive legal and financial costs might be greater than if one had simply backed up several times over the injured victim to make sure they’re no longer moving and then reported the homicide as an accident. If they’re dead, they can’t sue you. To be fair, most drivers wouldn’t have had the guts to go that extreme. But it happened enough over the years to generate unwelcome rumors about the practice, only to be confirmed when surveillance camera evidence began appearing on the Internet. Today, unless you’re on some backwater rural road and have a very bad stroke of luck, it’s unlikely to happen.

Wide boulevard in Ningbo, with two sets of pedestrian lights

Wide boulevard in Ningbo, with two sets of pedestrian lightsWhat might still happen, however, is that no one comes to your rescue if you’re struck. In decades past, you’d be surrounded by gaping onlookers while prone or supine on the street and nobody would call an ambulance or do anything to help, least of all the vehicle that hit you, now long gone. If anyone was stupid enough to take the initiative, they would be the only person you could latch onto and blame for the accident in order to extort thousands of Yuan out of them. After all the fact they’re coming to your aid only implicates them in their guilt, as you explain to the police when they finally arrive. Fortunately, nowadays street cameras are turning this notorious scenario into a thing of the past, and leaving the scene of an accident is less common. China has also amended its Good Samaritan laws to guarantee some degree of legal protection for people who come to the aid of traffic victims.

Shanghai deliverymen on e-mopeds

Shanghai deliverymen on e-mopedsVehicular dangers remain, though, in the form of that wild animal known as the electric moped. These beasts fly at you silently from every direction. The frantic deliverymen riding them have a delicate balancing act: getting their goods to you in record time so you won’t complain and cause their commissions to be docked, and not getting in an accident. But accidents do happen, prodding the authorities to bring back bike lines, some with guard rails rather than just a dividing line painted on the street surface. But on really busy thoroughfares like the East 3rd Ring Road in Beijing, bus lanes are prioritized, which e-bikes and regular cyclists must contend with. They are thus drawn to sidewalks and pavements, again because water finds the easiest path, not to mention that a collision with a pedestrian is preferable to that of a car. Still, the last thing deliverymen want is an accident. Their company will take the flak and possibly pay your medical bills, but the poor country boy will likely be out of a job, financially devastated in a lawsuit, or seriously injured. So they navigate among pedestrians very carefully — at speeds that nonetheless match that of traffic on the street.

Don’t make any unpredictable movements and you should be okay. Conscious of their presence especially when out walking at night, when I’m less visible, I frequently look over my shoulder for any e-bikes bearing down upon me, just as I used to look over my shoulder at suspicious footsteps when out walking in my hometown of Chicago. I’d wager your chances of being mauled in an e-bike attack in a Chinese city are statistically greater than being shot in a U.S. city. This brings me to my next series of observations.

Unusual police stations

Walking down the street in China, you may notice how little eye contact there is from passersby. It’s not that they’re afraid of you. Once again, the answer is quite simple. Just as there is no role for public space in China, so there is no role for public eye contact. Yet it’s not entirely a matter of indifference; by tradition, strangers are regarded suspiciously. On the other hand, crime is quite rare, and has gotten rarer over time. Back in the ’80s, it was prevalent enough that females were wary of being alone on certain city streets at night. But even then the incidence of street crime was probably less than it’s ever been in many countries, including the U.S.

Migrant laborer community on the outskirts of Beijing

Migrant laborer community on the outskirts of BeijingAfter almost three decades of living in China, I have yet to be a crime victim. I think back trying to recall incidents reported to me by others. Around two decades ago a friend’s apartment was broken into at night through their window and a few items stolen while they were sleeping. Also around that time, a construction worker at a university in Beijing where I was teaching raped a female student in a bush. In the ’90s it was not uncommon for women on crowded buses to have their purses sliced open from underneath and their cash plucked out. A few female acquaintances recounted how they had been flashed as children by adult male perverts, often a neighbor. A male coworker of mine around a decade back had a penchant for getting mugged as he staggered piss drunk out of a bar popular with foreigners on Beijing’s Sanlitun bar street. And there were rumors of a rather nasty crime on sleeper trains years ago: thugs going down the aisle knocking people on the head with hammers and robbing them, something that would be more or less impossible today on China’s high-speed trains with their advanced security systems (I have ridden sleeper trains many times and never had a problem).

Government billboard in a Ningbo park

Government billboard in a Ningbo parkNow that surveillance cameras have proliferated, violent crime is being threatened with extinction. Even before Big Brother’s increasingly voracious facial recognition capabilities, on whatever street at whatever hour of the night in whatever Chinese city, I can’t recall ever being remotely worried about being mugged. Things are becoming boring. There are fewer and fewer reports of crime in the news, only the occasional horrific event, such as the string of deranged men, out to get revenge on society, who went on stabbing sprees in primary schools some years back. Now schools typically have elaborate gates and armed guards. Another reason there’s not much crime in the news anymore is that the media are no longer allowed to report much crime. Cynics and Sinophobes might therefore assume the public is being kept in the dark and schoolchildren are continuing to be slaughtered. I don’t believe this is the case, as rumors would get around if it were. Whatever your position on censorship, one wonders whether the incidence of mass murders in the U.S. might decrease if the American media stopped reporting them.

Safe streets make for relaxed walking, even when the scenery isn’t very exciting. The long-reigning aesthetic was a top-down contempt for aesthetics. Chinese cities looked like industrial wastelands; many still do. You could walk for miles and not encounter a park. It was not until a decade or two ago that the concept of urban beautification took hold. Coastal cities built from scratch, such as Zhuhai and Shenzhen, and coastal cities razed and then rebuilt, such as Ningbo, Dalian, and Tianjin (with a memory of international influences and styles in their DNA) generally did a better job. Urban planning was now evident and generous parks sprung up.

Police station in Academicians Park, Ningbo

Police station in Academicians Park, NingboI’m walking down one such park today in Ningbo, a large wealthy port city south of Shanghai, with an unfortunate history of being attacked — by the British in the First Opium War in 1841, then by the Taiping rebels in 1861, and again by the Japanese in 1940 (who dropped a bomb containing the bubonic plague on the city). Academicians Park is a bucolic two-kilometer stretch of winding canals, arched stone bridges, and jogging paths. As I cross over a bridge in the middle of the park, I see a tall post with something familiar at the top — a surveillance camera — and on the other side, a cop car. Is that what I think it is? It is indeed a police station. Quite a substantial one in fact. There’s food for thought: a police station in a park. I saunter past and suddenly rather eager to leave cut across to the nearest exit, which faces the main gate of Zhejiang Wanli University. Ah yes, now I understand. The police station is there to protect and reassure the campus’s twenty-thousand students that it has their safety in mind! Curiously, though, I don’t recall seeing any students in the park.

Library with police station in Ningbo

Library with police station in NingboI continue along Qianhu South Road. Although this section of the city was only recently developed from reclaimed farmland, the landscaping is thoughtful and the street generously lined with trees on both sides. I come upon a library, a mammoth futuristic structure designated (in Chinese and English), “Library and Information Center The University Zone of Ningbo.” Is that again what I think it is, peeking out over the broad steps to the main entrance? I mount the steps and yes, there it is, a police station, our safety once more being considered. Especially in a library. How thoughtful of them. I’m presuming the “library” and the “information center” functions are kept separate so that users don’t have to ask the police how to find a book. Come to think of it, there’s been news of late that this law-enforcement creativity is now a major export as Chinese police stations have been popping up in many countries. Yet before you marvel at this dystopian achievement and congratulate yourself on living in a free society, let’s restore some perspective. Our own police stations may be less conspicuous, but in no country have I seen as many police cars prowling the streets as in the United States.

Nested cities

Before the end of Imperial China in 1911, Beijing was a nested city. A wall surrounded the entire city and access into the “Outer” or “Chinese City” was controlled through a series of gates to keep out the peasants and vagrants. A second wall within the Chinese city surrounded the “Inner” or “Tartar City,” reserved for the Manchus, who ran the capital (funds fell short and the Outer City wall ended up surrounding only the southern half of Beijing). Access to the Inner City was again strictly controlled to keep the Chinese residents out. A third wall within the Inner City enclosed the Imperial City, for the Manchu elite. A fourth wall within the Imperial City enclosed the Forbidden City, which housed the royalty. Beijing’s walls were designed both to keep the different social strata in their proper place and make it difficult for anyone to penetrate or attack the interior.

Beijing’s East 3rd Ring Road during a Covid lockdown

Beijing’s East 3rd Ring Road during a Covid lockdownIn the latter half of 2022, those of us living through Covid in China were growing uneasy and alarmed at the country’s epidemic measures. It seemed that the authorities weren’t planning on ending the lockdowns anytime soon but, on the contrary, wanted to bring back the nested-city tradition once and for all. In other words, the pandemic was merely the occasion for an ulterior purpose: to keep the population compartmentalized in their neighborhoods and restrict people’s movements as much as possible. For the first time in history, a powerful means became available for achieving this dour vision: the electronic tracking technology embedded in every citizen’s cellphone.

We could see the technology evolving step-by-step in this direction. In 2020, the first year of the pandemic, the measures were comparatively crude. We were issued passes for coming and going from our residential communities (which in China are usually gated; new gates sprung up where they hadn’t been before). Stores and restaurants required patrons to write down their contact information and have their temperature read with a thermometer gun. By year two, we had installed a government-mandated health app on our cellphones and were scanning the app’s QR code at the entrance to every shopping mall and again at every shop and restaurant within the mall. There was a justifiable rationale for this. The app indicated whether we had traveled to a Covid hotspot within the past two weeks. Were we in fact infected, they’d be able to trace the chain of transmission more precisely. Another measure was to require anyone traveling to another city to get a NAAT test (throat swab) within 48 hours of boarding a flight or train.

In year three, around the time of the Great Shanghai Lockdown (April-May), cities around the country began requiring everyone, not just travelers, to submit to regular throat swabs every 48 or 72 hours (sometimes every 24 hours; it varied from week to week). Fortunately, these mandatory tests were free and often conveniently located in makeshift booths in every neighborhood, but it did create massive inconvenience in terms of planning around them, going out of our way, and standing in line. There were three codes: green, yellow (you were overdue or in a hotspot), and red (you were Covid-positive or a close contact). You wouldn’t be arrested if you were overdue for a test (though some were indeed arrested by police who overstepped their bounds), but if your code was yellow, you were barred from all shopping malls, supermarkets, restaurants, hospitals, schools, buses, taxis, the subway, and even parks. (Some cities had an intermediate gray code, less severe than yellow but barring you from many public spaces and shopping malls.) If your code was red, you were promptly shipped off to a quarantine center or hospital.

Blockaded Ningbo street during a Covid lockdown

Blockaded Ningbo street during a Covid lockdownIt got worse. If you happened to be in a neighborhood where someone turned up positive for Covid, the affected area, which could involve several square kilometers of adjacent apartment complexes, was immediately locked down without warning. Some people were sent to quarantine centers with only a yellow code; others were reportedly barred from their apartment complexes and thus their own homes. If you managed to make it home but had been physically present in the affected area for up to two weeks prior to the lockdown, you were contacted by officials and forced to quarantine at home for two weeks. Hotels in affected areas were likewise locked down and guests stuck in their rooms for the duration of the quarantine period (and required to pay the daily rate), which could last weeks and occasionally months. Cities forbade entry to visitors; existing visitors not allowed back home were stranded. Airline, train, and bus service was severely cut back or halted altogether in any case. In the chaotic final months of 2022, as the virus broke through and spread uncontrolled throughout China, whole cities underwent rolling lockdowns, with all businesses closing and people confined to their communities or complexes. Barricades started appearing everywhere, blocking streets and corralling people like animals into a dwindling number of narrow corridors.

Beijing’s East 3rd Ring Road

Beijing’s East 3rd Ring RoadWhile the government was trumpeting its success in keeping the virus out of the country, the depressing realization took hold that the lockdown measures had nothing to do with public health and everything to do with power for its own sake. The authorities had discovered how remarkably easy it was to control the entire population down to every citizen through the electronic leash known as the cellphone, and it was thoroughly intoxicated by this power. How could they ever give up the drunken magic of this newfound omnipotence? They didn’t have to do anything as long as the cellphone was people’s most prized possession. We began to envision a world — some were calling it the “North Koreanization” of China — in which the virus was long gone and the same “health” apps would remain in place to micromanage a population now rendered wholly powerless (allegedly, North Koreans are only permitted freedom of movement between their home and workplace). The Chinese would no longer be allowed out of the country to travel or emigrate, and international tourism to China would be dead in the water, as no foreigners would put up with installing Chinese surveillance apps on their phones. And all the billions lost from the tourism economy? The tradeoff would be well worth it from the government’s perspective, as they would have achieved what no other regime had ever managed: a perfectly stable, obedient, and orderly society, the dovetailing of Orwell’s 1984 with Huxley’s Brave New World.

One became conscious of freedom of movement as a right even more basic and important than freedom of speech. How dare they prevent people from getting on with their essential movements, their multiplicity of activities and places, their jobs, their lives? I think there was a critical mass of revulsion that finally brought the pragmatists in the government to their senses in January 2023 with its sudden about-face. Even they didn’t like what they saw when they looked in the mirror. Of course, they had already lost the battle with the virus, the economy was in freefall, and they really had no choice. The collective relief we all experienced was palpable and orgasmic, so much so that one suspected it was all part of the plan. Hatred had been building — and suddenly, happiness and joy as the government appeared to wash its hands of the whole pandemic nonsense faster than anyone could process.

A brigade of disinfectant sprayers on a Beijing street during the 2022 pandemic drive

A brigade of disinfectant sprayers on a Beijing street during the 2022 pandemic drive* * *

Forthcoming:

Insights into China (Part 2/3): A visit to a restaurant

Insights into China (Part 3/3): A stay in a hotel

Other posts of interest by Isham Cook:

Sexual Surveillance in the Covid-19 era

How to have fun in China’s disposable cities

The Chinese art of noise

The poverty of the institutional imagination: The case of Beijing’s moats and canals

The ventriloquist’s dilemma: Asexual Anglo travelogues of China