The Mysterious Mr. X

It seems like everybody knows someone who they believe was or is a spy.

Having been living for nearly twenty years within a hundred miles of the cloak and dagger hubs of the USA – Quantico (the FBI and U.S. Marine base) and Langley (CIA) – my husband and I have been privy to no shortage of tales about the sleepers among us. Like this one guy who retired and did a bit of carpentry work on the side. Our local girls’ tennis coach was sure he was definitely a spook. I mean, he’d worked at Langley as an accountant, or so he claimed. Then there was the foreign affairs professor who took a lot of sabbaticals and yet never seemed to write any books. And the new guy down the street who, when pressed about what he did for a living, mentioned that he had a few small business ventures going, but then quickly changed the subject.

Most of these are probably B.S.

The retired accountant turned carpenter-for-hire sure comes off like a bean counter to me and gives pretty good advice in that arena. The foreign affairs professor appears way too compliant to risk stealing sensitive information that could land him in prison, and too socially awkward to pull off cultivating the kinds of relationships that would even get him access to high-level intelligence. As for the small business guy – he might just be living off of a trust fund and didn’t want to admit it in front of a bunch of scrappy self-starters. Or genuinely hated talking shop at the neighborhood barbeque.

But there was one man I not only heard stories about but got to know a little bit, who truly may have been a spy. A man who for our purposes, I’ll call Mr. X.

“Do you remember {Mr. X}?” our family friend Albert asked me, when he came to town for his college reunion a couple of months ago. “He died last summer.”

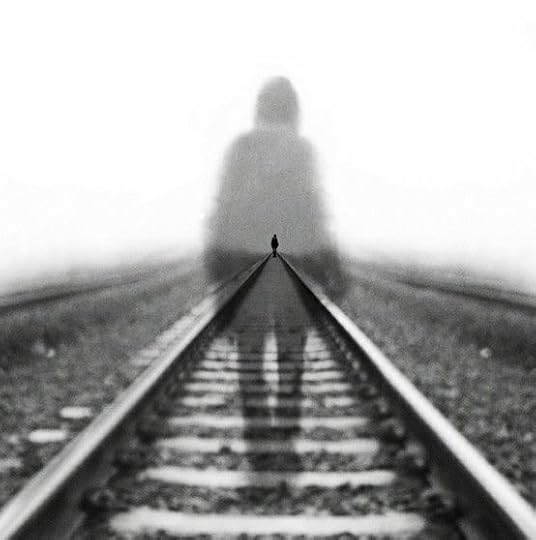

I told Albert that I did remember him, and very well, although I’d only met him once or twice. There was a weight to him, a soulfulness, loneliness. While my encounters with Mr. X had not been what I’d call dark and inscrutable, he was the quiet type, who didn’t give a whole lot away. To be honest, my impressions of our past interactions…were mostly sad. He was a man who knew regret and didn’t flinch about facing it, never rationalized it the way an unfaithful spouse might, saying something like, “I know it was hard, but in the end the divorce was actually good for the kids.”

Now Mr. X was no longer among us, and I felt a genuine sense of loss.

What lingered like a valley fog from the few times I’d found myself chatting with him was the way he’d talked about his personal life, or lack thereof. How he’d never thought he was ready for love and had watched good women come and go. How he’d tried to start over a couple of times, but realized it was too late. He’d made his bed. There wasn’t any self-pity in these revelations, nor any detail. Most of the time when I found myself in his company, he seemed content just to let other people talk. And to listen. I always got the feeling that he really listened.

“What bothers me is that he died alone,” Albert said.

Our friend disclosed that he’d been thinking about Mr. X a lot. About their history together. The two men had been very close once, having been in the same fraternity at University of Virginia. They’d both studied law and had stayed in touch over the years, even between college reunions. In fact, Albert had called Mr. X on the day his body had been discovered, wondering if he was planning to attend the most recent one. The moment his niece answered the phone, he knew, Albert told us. Nobody else ever answered Mr. X’s phone.

“He was a natural leader, you know,” Albert said. “He never used force to get his ideas across, although he was strong and athletic.”

Albert went on to describe Mr. X’s unwavering moral code and deep sense of honor. How much women liked him and professors held him in high esteem. He also described how Mr. X had fallen off the radar for a while after graduation, and resurfaced intermittently, in between to ambiguous consulting jobs or business opportunities in countries like Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Romania, Ukraine.

Then, there were the injuries, which had him coming back to the U.S. to recuperate at times for months on end, before he picked himself up and went abroad again.

“They weren’t the usual broken ankles from a ski trip,” Albert said. “They were strange, like he’d been beaten up. He’d say he fell or was in an accident, but it never seemed right. Like the battered wife who claims she tripped down the stairs one week, then walked into a door the next. There was always something.”

Albert was troubled that hardly anyone had shown up to Mr. X’s funeral, too. “Only six people came, and that included me and my wife and son. He was popular at school, always there to help when you needed him, and this was the turnout. Not even the rah-rah guys from our fraternity came to pay their respects.”

It didn’t surprise me, but then again, I hadn’t known Mr. X when he was a college student. The man I had known – however little and however briefly – had seemed an orphan in this world. I couldn’t imagine him with a mother and father or siblings and was even surprised to hear that he had a niece who was attuned enough to his comings and goings to discover his body.

“He should’ve married and had kids,” Albert said. “You need family in this world.”

Maybe Mr. X really was just an emotional ne’er-do-well, who’d taken on adventurous business consulting opportunities in favor of settling down, and eventually all of that had caught up with him. His curious injuries, I’m sure, could be explained away by a competent physician.

And people change, after all, sometimes becoming estranged from friends and family as they grow older. It’s not a trait that can only be attributed to those who enter the world of espionage. Even an affable frat guy like Mr. X could have had a stranger lurking within him all along. One who only needed permission to surface.

But none of this seemed to be enough to explain how a man who reeked of depth and dignity could have ended up so far from where he’d started – and without help from the usual accelerators of doom: sex, drink, and drugs.

In my estimation, the reason why Mr. X seemed like a plausible spy was more ambiguous than the way he’d lived his life – always on the move, reticent about revealing too much, unable or unwilling to make a commitment to anyone. What stuck in my craw, was that unlike the Langley accountant, Mr. X hadn’t retired and started making furniture. He hadn’t moved on to something else or held on to what he had. Here was a man of intelligence and charisma, good looks and good character. He’d started off his young adult life by going to an excellent school, where he’d joined a prominent fraternity and earned the respect of its members, who all thought a guy like him was going places.

In short, he’d been a man of promise.

Yet, at the end of his life, no one really knew Mr. X. Not even Albert, who’d always been the one to initiate contact, who’d tried to help him meet a woman and relaunch his life, who’d flown his family from their home in San Francisco to Portland, Oregon, for Mr. X’s funeral. Almost everyone but Albert had long since stopped trying to know him, worn down by the unreturned phone calls, the far-flung assignments, the strangeness, otherness of Mr. X’s life choices.

If he really was a secret agent, I’d like to think it had all been worth it for Mr. X – the injuries and clandestine missions. They may have meant a great deal to the young men who fight in our wars, the people who are victims of true oppression, and the world at large. Even if they did ravage the life of the man who undertook them.

But the truth is, the spy is the ultimate unsung hero, so we’ll never know.

If you have a taste for some fictional spies of my making…

The Hungarian in trade paperback is on sale at Amazon: