Readers vs. Gatekeepers

Nothing grates my cookies the way literary gatekeeping does.

Growing up, I loved to read, but I wasn’t allowed to go to my school library because the book collection was deemed “90% inappropriate.” My personal gatekeeper, who kept me from the books they feared, wanted to go a step further and remove those inappropriate books to “protect others” claiming it was the librarian who had provided that horrific statistic.

Actually, what the librarian said to the gatekeeper was, “If we took out every book that offended you, 90% of the collection would have to be removed.”

My gatekeeper never understood that they came out of that exchange looking ridiculous. Instead, they were proud of their stance and bragged about it for years.

Living with my gatekeeper meant that every book I purchased was met with handwringing and fear that it might “lead me astray” or “poison my mind.” Weirdly, this cloud of anxiety also hovered over their own heavily curated shelves filled with biographies and autobiographies of missionaries, church workers, evangelists, and Christian musicians. Even when selecting books from their collection, I was criticized as my gatekeeper suggested I was looking for something salacious. At the time of that accusation, I was reading a book about a couple preparing to go on the mission field. I had mentioned that the man had a heart condition and when he started having pain and palpitations, his wife was instructed to put an ice compress on his chest. I remember asking about that treatment since I’d never heard of such a thing before. I still don’t understand what it was about that scenario that the gatekeeper found scandalous.

As a teen, I did have two Grace Livingstone Hill books that had been passed down to me from trusted family members, as well as a copy of Anderson’s and Perault’s fairy tales that had been in the family for decades, but no one read. I read those, and other “approved” books, on repeat. I appreciated that my gatekeeper bought me a collection of Danny Orlis books reprinted by Moody Press and a few Scholastic volumes that had made the cut. Since my gatekeeper was also my authority, they had the right to guide my reading choices. However, their desire to have such tight control extended outside our relationship to others under their influence as church leader and Sunday school teacher.

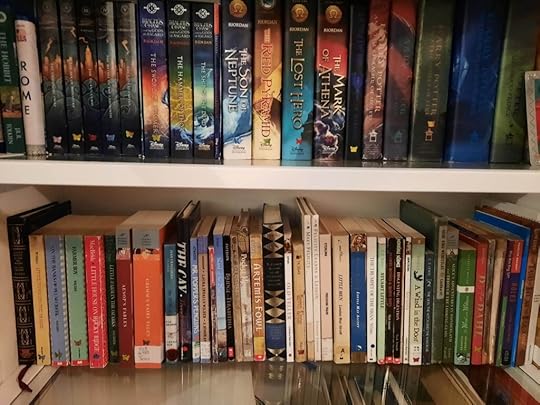

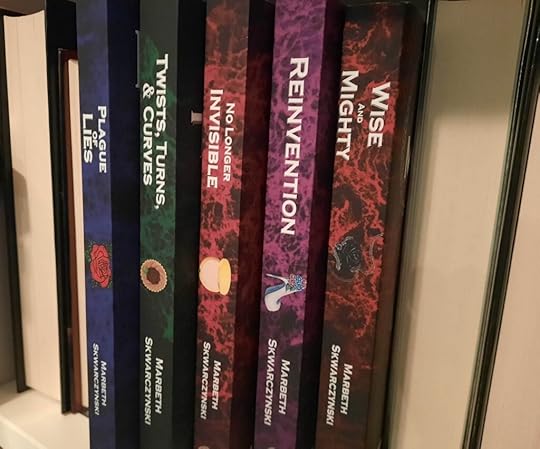

I’m long past those teen years, with children and grandchildren of my own, but the self-appointed gatekeepers still irritate me. As an adult, I created some beautiful home libraries and became a full-time writer, publishing six books of my own. I’ve decided that gatekeepers will no longer keep me from reading what I want. Still, just as my previous gatekeeper doesn’t like my books and discourages people from reading them, I know other gatekeepers are campaigning against books by other authors. Their influence prevents readers from finding books that they might enjoy.

Gatekeepers love power. They want to be heard and obeyed without question or confrontation. They see critical thinkers as idiots who don’t know when to sit down and shut up. The gatekeeper knows better.

The church I used to attend had a prominent literary gatekeeper come a few times a year to preach. He was a history professor at a Bible college who spent most of his weekends on the road promoting the school. His time behind the pulpit was focused on scaring parents, warning them against letting their kids read anything new or contemporary. He bragged about having a huge library of classic literature and Bible studies in his home. He also stated that he read lots of popular magazines (to keep up with current events), subscribed to housekeeping journals for his wife (because they had recipes), and did not have a television or DVD player in his house (since they were time wasters). The message was clear. He was spiritually superior to just about everyone. Still, there was the unspoken promise that if a young person committed to attending his Bible college for four years, they could be spiritually superior too.

For parents with younger children, he discouraged them from taking their kids to places like Disneyland or Knott’s Berry Farm because they were “amusement parks” and “a-muse” means “without thought.” To help children think, he strongly suggested that parents make sure their kids read only classics. Still, the only classic book I remember him suggesting was Captain’s Courageous by Rudyard Kipling. It’s a good book, but not exactly to everyone’s taste.

He let the congregation's adults know that they should not be reading popular literature either. They could read Bible studies and biographies published by the college he represented, but he had nothing else to recommend outside of those.

During one particularly crushing sermon, I decided to write down the titles he suggested were drawing Christians away from godly living. I made a point of reading those books, making notations in the margins, and discovered that he had grossly mischaracterized their messages.

While some gatekeepers disguise their superiority by claiming they are looking out for God’s people, not every gatekeeper’s motive is spiritual. I’ve encountered many who inflate their egos, using condescension and disapproval to discourage people from reading books by specific authors. Unfortunately, I’ve also read many posts by readers who apologize for even admitting that they like those heavily criticized books.

Readers shouldn’t feel the need to express regret for enjoying what they read.

To be clear, gatekeeping isn’t the same as personal preference. Most readers have genres they cling to because they love the writing style, time period, or world-building. Some exclusively read non-fiction. Others read a mix of non-fiction and fiction and a wide variety of genres. All of that is great.

Gatekeeping is when a person demands that everyone read only what THEY believe is appropriate. That’s when you hear sweeping statements like, “No Christian should read romance,” “We need to tell Christian authors to talk more about Jesus in their books,” “No truly educated person would read today’s popular fiction,” “That author’s style is so amateurish, that I would never let my child read her work,” “That book has the wrong message for teens, and it shouldn’t be sold at Target/Walmart/Barnes and Noble,” “I want my children to only read the classics.”

As both reader and writer, I see statements like these on social media a few times a week, so I’d like to address them.

“No Christian should read romance” is such a weird statement. Romance isn’t my favorite genre, but I greatly respect the authors who can follow the strict guidelines of that category and create original stories within those parameters. In some Christian romances, the books take on deep, profound messages. It isn’t just meet-cute, misunderstanding, and a declaration of love followed by a quick resolution. The characters go through deep introspection, spiritual growth, and emotional development. While there is physical attraction, the primary focus is on inner work and seeking to spend life with a fellow believer.

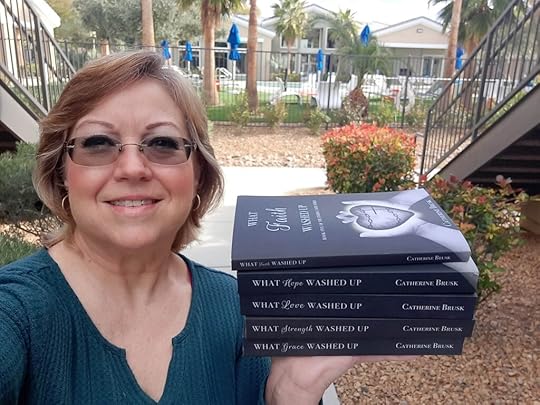

Catherine Brusk: books, biography, latest update

This week, I ran across a post stating, “We need to tell Christian authors to talk more about Jesus in their books.” It went on to declare that without Jesus, the books are worthless, and too many Christian authors aren’t focusing on Him the way they should. As a writer of contemporary Christian novels, this one rubbed me the wrong way for a couple of reasons. First, no one needs to tell ANY author what they should write. If you see the necessity for a book to be written, write it yourself. It is that drive that creates authors in the first place. As for the second part of the statement that Christian authors aren’t focusing on Jesus “the way they should,” my initial response is “who decides what that ‘should’ looks like?” My characters are recovering from spiritual abuse while clinging to Scripture and rediscovering the real love of Christ in their lives. Would someone read my books and say, “Nope. Not enough references to Jesus”? I have no idea, but if they did, I’d wonder if they missed the point of my novels.

Because I read and write contemporary fiction, I can’t help but feel a little sad when a gatekeeper degrades “today’s popular fiction” (not that my books are at all popular). I love popular as well as indie and some upmarket fiction. The idea that “popular” should have a negative connotation seems odd. Historically, serial works by Dickens were so popular at the time of their publications that the magazines sold out, people wept en masse when a beloved character died, and there was discussion of his work across lines of age, class, and gender.

Today, some gatekeepers believe that if the majority of the populace enjoys something, it must be garbage. That says more about the people who hold themselves above “the commoners” than the literature they’ve rejected. But, again, if it were just their opinion, tightly held for themselves, it wouldn’t be a problem, but when they feel compelled to denigrate those who might like popular fiction (or any other genre), it crosses the line into bullying.

“That author’s style is so amateurish that I would never let my child read her work,” and “That book has the wrong message for teens, and it shouldn’t be sold at Target/Walmart/Barnes and Noble” are statements I’ve heard about women authors specifically — almost exclusively. For some reason, women gatekeepers have gone after women writers as if they get paid for each hurtful remark they make. Usually, their statements are based in ignorance, where they accuse an author of promoting a toxic relationship or behavior simply because it exists in the text. There is no acknowledgment that the toxicity is addressed and rectified in later pages — or that it is simply a callback to a previously written book of the same genre.

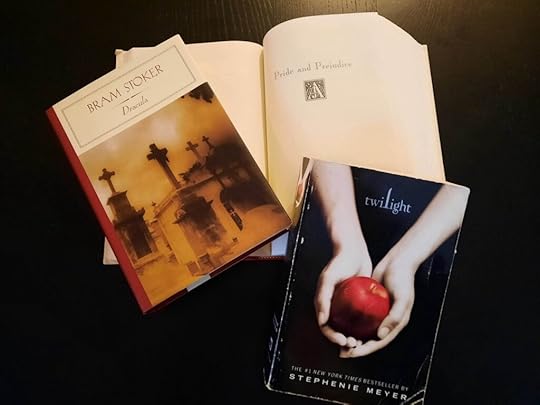

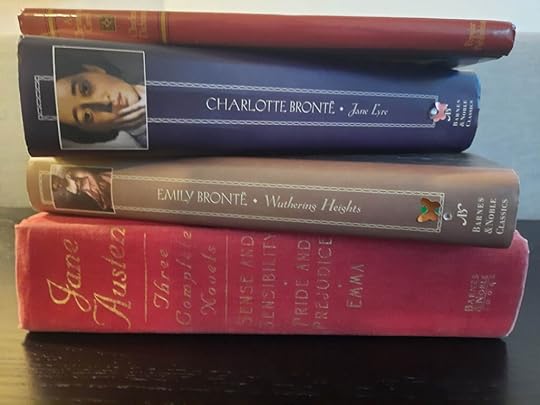

“I want my children to only read the classics” is a noble goal, but I like to point out that every classic began as a work of pop culture. When Pride and Prejudice was first published, it was contemporary fiction. So were Moby Dick, A Christmas Carol, Wuthering Heights, and Jane Eyre.

While Frankenstein and Dracula were categorized as gothic horror, they were also contemporary works. Among those who believe others should only read classics — to the exclusion of contemporary works — there is a willful ignorance that some of the books being written today may be considered classics in the future.

Responsible parents will, of course, engage with their children when selecting books to read. They’ll preview, read, and discuss, not as gatekeepers determined to crush others with their expectations and restrictions, but as fellow lovers of the written word.

Readers tend to be an encouraging lot, more now than ever with Facebook groups, Bookstagram, BookTok, Goodreads, and Readers of Twitter. The gatekeepers will still have their say — we’ll never be able to change their minds — but we can move past their prejudices and read what is best for us.

And we can urge others to do the same.

Marbeth Skwarczynski: books, biography, latest update

[image error]