The Father of Deliberate Practice Disowns Flow

Feeling Low on Flow

In a trio of recent articles, I emphasized that flow is dangerous (see here and here and here). It feels good, so we’re tempted to seek it out, but it doesn’t actually help us get better: the key process in creating a remarkable life.

Most of you liked this concept, while a few of you thought I had missed the boat. Here’s an example of the latter sentiment:

I disagree with [your] point. Flow is the experience of being lost in one’s effort. That can easily happen when one is highly challenged and enjoying the intense effort.

There was also quite a bit of discussion on what, exactly, “flow” means, with enough different points of view presented that I soon felt that the whole issue was becoming muddied and difficult to wade through.

Then someone sent me an article penned by Anders Ericsson — the psychologist who innovated the study of how we get better by introducing the idea of deliberate practice. In this article, which was published in 2007 in the journal Current Directions in Psychological Science, Ericsson addresses the difference between flow and deliberate practice:

It is clear that skilled individuals can sometimes experience highly enjoyable states (‘‘flow’’ as described by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, 1990) during their performance. These states are, however, incompatible with deliberate practice, in which individuals engage in a (typically planned) training activity aimed at reaching a level just beyond the currently attainable level of performance by engaging in full concentration, analysis after feedback, and repetitions with refinement.

In other words, the feeling of flow is different than the feeling of getting better. If all you seek is flow, then you’re not going to get better. There is no avoiding the deliberate strain of real improvement. (This is not the say, however, that you should not seek flow in addition to deliberate practice as a strategy to recharge, or experience it as unavoidable when you put your deliberately honed skills to use.)

Ericsson concludes by echoing a warning familiar to Study Hacks readers:

The commonly held but empirically unsupported notion that some uniquely “talented” individuals can attain superior performance in a given domain without much practice appears to be a destructive myth that could discourage people from investing the necessary efforts to reach expert levels of performance.

He said it. Not me.

#####

This post is part of my series on the deliberate practice hypothesis, which claims that applying the principles of deliberate practice to the world of knowledge work is a key strategy for building a remarkable working life.

Previous posts:

The Satisfying Strain of Learning Hard Material

Beyond Flow

How I Used Deliberate Practice to Ace my Computer Science Final

Flow is the Opiate of the Mediocre: Advice on Getting Better from an Accomplished Piano Player

Is Talent Underrated? Making Sense of a Recent Attack on Practice

Perfectionism as Practice: Steve Jobs and the Art of Getting Good

Complicate the Formula: John McPhee’s Deliberate Practice Strategy

If You’re Busy, You’re Doing Something Wrong: The Surprisingly Relaxed Lives of Elite Achievers

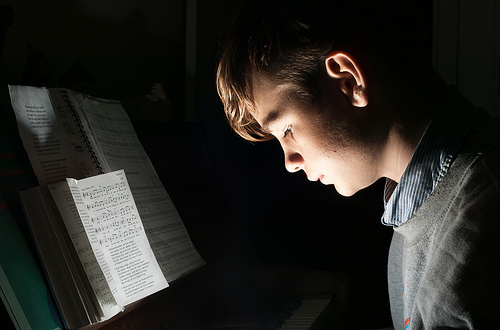

(Photo by Kofoed)

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9951 followers