CMP#127 Methodism and Some Memories

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. CMP#127 Portrayals of Methodism in the long 18th century, part one Growing up as I did in the Methodist church, I took it for granted that we Methodists were the very essence of rectitude and respectability. I had no reason to question it. See that row of men at the back of the photo below, taken at the old Cummins homestead in Southern Illinois? Many of my ancestors were Methodist ministers, including many of the men in that photo. The extended clan--everyone dressed up in their best attire--would have enjoyed

chicken and dumplings

and some hand-churned ice cream, but there would have been no drinking and no smoking. My own family bent the rules in a few instances--my parents (who met at a Methodist youth conference) were good ballroom dancers. My maternal grandmother played the pump organ for her husband's congregations. During the week she enjoyed a game of gin rummy or pinochle but of course no wagering on the outcome.

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. CMP#127 Portrayals of Methodism in the long 18th century, part one Growing up as I did in the Methodist church, I took it for granted that we Methodists were the very essence of rectitude and respectability. I had no reason to question it. See that row of men at the back of the photo below, taken at the old Cummins homestead in Southern Illinois? Many of my ancestors were Methodist ministers, including many of the men in that photo. The extended clan--everyone dressed up in their best attire--would have enjoyed

chicken and dumplings

and some hand-churned ice cream, but there would have been no drinking and no smoking. My own family bent the rules in a few instances--my parents (who met at a Methodist youth conference) were good ballroom dancers. My maternal grandmother played the pump organ for her husband's congregations. During the week she enjoyed a game of gin rummy or pinochle but of course no wagering on the outcome.  Growing up, I absorbed a little of the history of Methodism and again, I only heard what was good. I learned how Methodists urged working families to stop drinking gin and switch to tea instead. I pictured Methodists as a civilizing force in the 19th century. And I had respect for the passion and sincerity of Methodism’s founders, the Wesley brothers.

Growing up, I absorbed a little of the history of Methodism and again, I only heard what was good. I learned how Methodists urged working families to stop drinking gin and switch to tea instead. I pictured Methodists as a civilizing force in the 19th century. And I had respect for the passion and sincerity of Methodism’s founders, the Wesley brothers.That’s why, when I started my project of reading novels of the long 19th century, I was both amused and surprised to learn that Methodist preachers were portrayed as grifters who took advantage of the credulity of the poor and ignorant.

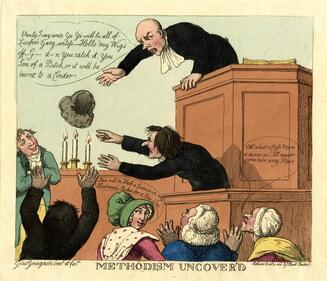

Some plays and novels of the long 18th century offered commentary on Methodists and Methodism (they seldom capitalize the word as we do today), and there were some satirical cartoons too. Although Methodism first arose in Oxford, Methodist ministers were portrayed as uneducated hypocrites.

Some plays and novels of the long 18th century offered commentary on Methodists and Methodism (they seldom capitalize the word as we do today), and there were some satirical cartoons too. Although Methodism first arose in Oxford, Methodist ministers were portrayed as uneducated hypocrites.In the cartoon at right, the minister starts swearing when his wig falls off, probably because he was leaning out and gesticulating wildly: "Verily I say unto Ye. Ye will be all of Lucifer's Gang, unless - Hollo! my Wig's off - G[o]d[am]n You catch it, You Son of a Bitch, or it will be burnt to a Cinder". His language shocks the old woman who vows never to return, and a knowing young lady turns around and suggests that the minister will collect "half a guinea for a new one."

There’s a passing reference to grifting preachers in the comic play The Votary of Wealth (1799), in which Leonard Visorly, a roguish character, is accosted by name a man in Methodist garb, who greets him with : "Peace be unto this house!"

“Who is this?” Visorly responds, surprised. “With what hedge divine have I the honour of an acquaintance?” (The term “hedge divine” is a reference to the fact that these ministers, working outside of the established church, often preached in the open fields.)

It turns out the fanatical preacher is none other than Visorly's fellow swindler and former partner in crime, Jeremy Sharpset. He tells Visorly that since the two of them parted ways, he has been doing “all sorts of things I ought not to do.” He tried speculating in trade, operating a menagerie, joined a troupe of travelling actors, and finally turned preacher: Oh, then I got a call [as in “a calling”], and mounted the habiliments in which you see me; this was lucrative; but my conscience would not suffer me any longer to drain from the pockets of the poor the earnings of their industry; nay, what is worse, embitter their innocent minds with groundless terrors, and inspire them with prejudice against their fellow-creatures… Upon my soul, I am tired of being a rogue. We meet a more dedicated conman in The Bristol Heiress (1809) by Eleanor Sleath. Sleath ties her social commentary about Methodism to a common 18th century novel trope: the heroine, orphaned and reduced to poverty, must go live with unpleasant relatives who reluctantly take her in. Sometimes the relatives consist of plain female cousins who are jealous of the heroine’s beauty, sometimes the relatives are insufferably vulgar. In this case, all of the above applies but as well, the heroine’s aunt has fallen under the sway of Mr. Enfield, a Methodist preacher who is presented as a grifter and the leader of a “deluded and fanatical sect.”

Mr. Enfield “had been formerly of the laborious profession of a blacksmith; but had, of late, by means of some abilities, more cunning, and a most extraordinary stock of impudence, raised himself to no small degree of eminence and popularity; and had thus found the means of maintaining himself much more glory, and much less labour, than by his original calling. To the grimace of methodism, he added a certain easy flow of whining elocution, abundantly seasoned with Scripture texts.”

A man could become a Methodist preacher, I gather, without having attended Oxford or Cambridge or any college whatsoever. One could operate outside of the established church and survive on whatever your congregants chose to give you. One can see how this would be a fertile ground for eloquent con men.

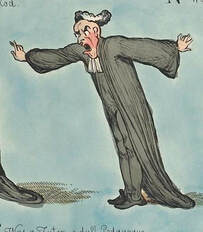

A Methodist Preacher- "quite mad!" from "A Clerical Alphabet" Mrs. Benson, the heroine’s widowed aunt, is portrayed as not overly bright; “the unfortunate victim of credulity and religious fanaticism.” Her conversion to Methodism alienates her from her adult children and Mr. Enfield becomes her companion and trusted advisor. “In the management of both Mrs. Benson’s affairs, both temporal and spiritual, the wily preacher found ample scope for the exercise of [his] cunning… He knew Mrs. Benson had the disposal of a considerable property…. Having already brought her mind to a state bordering upon insanity, by flattering her hopes, or alarming her fears, about the state of her soul…

A Methodist Preacher- "quite mad!" from "A Clerical Alphabet" Mrs. Benson, the heroine’s widowed aunt, is portrayed as not overly bright; “the unfortunate victim of credulity and religious fanaticism.” Her conversion to Methodism alienates her from her adult children and Mr. Enfield becomes her companion and trusted advisor. “In the management of both Mrs. Benson’s affairs, both temporal and spiritual, the wily preacher found ample scope for the exercise of [his] cunning… He knew Mrs. Benson had the disposal of a considerable property…. Having already brought her mind to a state bordering upon insanity, by flattering her hopes, or alarming her fears, about the state of her soul…We are told that Enfield does not resemble that austere-looking “celebrated divine” the “famous Westley [sic].” Enfield is plump, moon-faced, and enjoys the good things in life. He is fond of a hearty meal and a constant supply of rum and water.

Having failed with her own children, Mrs. Benson attempts to convert her reluctant niece Caroline (the heroine). In one passage, Enfield scolds Caroline for believing the that “good works” have anything to do with salvation. This is a doctrinal dispute familiar to historians of the church—do we obtain salvation through good works, or through faith alone?

The author then goes on to describe a Methodist service held at Mrs. Bensons’ house: ”[A] noisy tempest of words” from Enfield met with “sighs, sobs, groans, and tears… [and] the most frantic ravings and violent gesticulations, sometimes performed standing, sometimes on the knee, and sometimes, if possible, on the floor. In the meantime Enfield continued his threats, exhortations, invocations, and anathemas… till, at length, the loudly roared hymn brought them once more to order, and finished the confusion of this modern Babel.” Unusually—you might even think unbelievably—my father, a white man, was ordained to the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church and that’s the church I grew up in. This is because he and my mother had volunteered to go to Korea as teaching missionaries, and it was deemed that a stint in a black congregation would give my father (in his early twenties at the time) a foretaste of working in a culture that was foreign to him.

Sleath’s description of a Methodist congregation bears no resemblance to the AME congregations of my childhood, nor were they ever as lively as the portrayals of black congregations that you see in the movies with dancing in the aisles and a screaming preacher. My father was an excellent speaker, but he didn’t go in for ranting and raving, and neither did any other AME preachers I heard. The ladies wore hats and gloves, and we did have the paper fans to wave, with a picture of the Last Supper on one side and an advertisement on the other. And of course, we had the wonderful Wesleyan hymns.

At any rate, Mr. Enfield’s sermon in The Bristol Heiress is followed by a dinner provided by Mrs. Benson, at which all the congregants gorge themselves and then carry away any leftovers they can shove in their pockets “without concealment or reserve.” The heroine is dismayed and disheartened at witnessing “one of the most extraordinary scenes which can possibly be exhibited in a Christian country.”

Well, in the AME church we didn’t have a potluck every Sunday, but when we did—wow, what a feast. But it was a potluck; every family contributed, and I imagine that the ladies piqued themselves on bringing their very best. But, to pull myself away from the fried chicken, ambrosia salad and devilled eggs of church basement memory and back to the long 18th century….

Caroline goes on to live with another family and has more hardships and misadventures and the Bensons largely drop out of the story. At the conclusion of the novel, we’re told Mrs. Benson’s adult children successfully contested their mother’s will—made under Enfield’s influence--and he does not succeed in obtaining her fortune upon her death. We meet another dishonest Methodist preacher in Anna, or Memoirs of a Welch Heiress (1796). Anna is left as an orphan foundling at an inn. Mrs. Clarke, the innkeeper, hands the infant over to her minister, who belongs "to a Methodist conventical in the neighbourhood,” along with the orphan's travelling trunk. The Reverend Dalton discovers that the trunk contains “the exact sum of fourteen hundred guineas… three valuable diamond rings, and a lock of hair folded up in lawn paper…” These finds he keeps to himself. He gets all the credit for charitably taking the foundling girl into his own large family. His greed prevents Anna from learning anything about her possible origins. Not only does he keep the money a secret from her, once she grows up, he threatens to sue her for the cost of her maintenance and send her to debtor’s prison. Luckily, she is coincidentally reunited with Mrs. Clark, and learns enough to uncover the truth. The previous examples show Methodism as its worst, as a harmful set of beliefs perpetrated by unscrupulous men for their own advantage. In the next post, examples from novels of how Methodism deranged the intellects of the poor and inoffensive cottagers who fell under the sway of these ministers.

Last post: Austen Memoirs and Meditations If you'd like to learn more about religion in the time of Jane Austen and how it informs her novels, you must get yourself a copy of Brenda S. Cox's new book Fashionable Goodness.

When I created a romantic foil for Fanny Price in my Mansfield Trilogy, I devised the character of a radical young poet and abolitionist, William Gibson. I named him after William Gibson the science-fiction writer, whom I had briefly known in Vancouver before he became famous. At any rate, my William Gibson strode onto the pages of my first novel and announced that, although he'd been destined for the church, he was a free thinker and an atheist. I, too, have become an apostate and am at best a luke-warm Deist. However, I still contend that a knowledge of the literature of the bible and church history is important for understanding Western literature and I wouldn't trade my memories of Sundays in the AME church for anything.

Published on January 15, 2023 15:13

No comments have been added yet.