The Engineering Marvel of Rome’s Public Baths

Caraculla Baths

Lecture 15: Paradigm and Paragon—Imperial Roman Baths

Understanding Greek and Roman Technology: From the Catapult to the Pantheon

Dr Stephen Ressler (2013)

Film Review

According to Ressler, the first public baths appeared in Minoan Crete during the Bronze Age (3500 – 1000 BC) and served a ritual function for the elite. The Greek city states built the first baths for the public at large. Numerous persons sat in individual tubs in the same room while an attendant poured cold water over them. Plato asserted that warm baths were only for the old and sick.

During the Hellenistic Period (post Alexander the Great 323 – 33 BC) public baths began offering saunas and bathtubs began appearing in private homes.

The first hot water baths in the Republic of Rome emerged during the third century BC in southern Italy, perhaps in imitation of nearby natural hot springs. Between 200 and 100 BC, public baths featuring a sauna, hot bath, cold plunge and massage became extremely popular. Emperors built baths to manifest their power and to curry public favor. By 30 BC, there were 170 baths in the city of Rome alone.

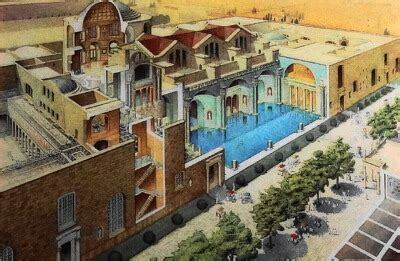

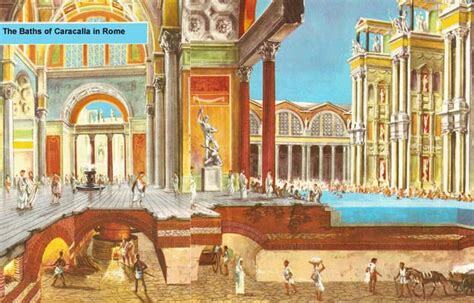

Today the best preserved Roman baths those in Caraculla, south of the Palatine Hill. Construction on the Caraculla baths, which were larger than four football fields, began in 213 AD. Opening in 216 AD and serving 6,000 bathers a day, they provided exercise areas and changing rooms, as well as saunas and communal baths with hot (calderia), tepid (tepidaria) and cold water (fridgidarium).

Structural engineer Janet Delaine has published detailed schemata of the complex process required to construct the baths, which Ressler recreates with detailed drawings and scale models. The first step was to build a new aqueduct to supply the sites cistern with three million gallons of water a day to mix the tons of cement required for the foundations and walls. Doubling as a retaining wall, the Carucalla cistern was an exception to the continuous flow featured in other public baths and fountains. Once the baths began operating, the cistern was filled at night to avoid disrupting the city’s water supply.

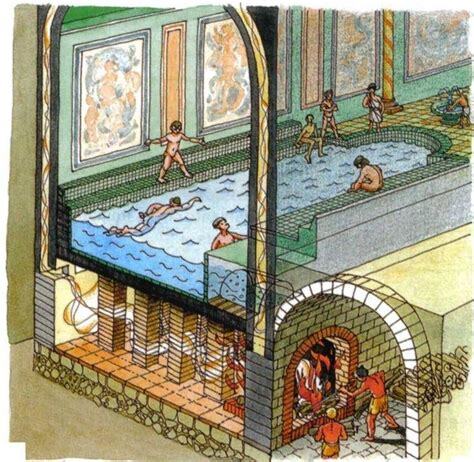

Construction workers began by digging a subterranean terrace they used to lay a 15-20 foot foundation made of standard opus testaceum.* They used a timber frame, which eventually rotted away, to pour concrete mixed with basalt for etra strength. Next came the bath’s subterranean structures: the sewer (a vaulted brick gallery), lead pipes to supply water, vertical drain pipes for rainwater and waste, maintenance galleries and multiple passage ways. The maintenance galleries were necessary to access the 50 furnaces heating the paths. They had to be 20 feet wide to support horse drawn wagons carrying wood, while simultaneously incorporating skylights for illumination, feedings troughs for horses and storage rooms accommodating 2,000 tons of firewood.

Next 4,000 masons and bricklayers and stone masons used wooden scaffolding to build the the 80 foot walls, which used embedded relieving above doors and windows to provide additional support. The walls also included built-in roof drain pipes, channel supply pipes, interior staircases and heating flues. Building used a wide variety of barrel vaults, groin vaults and semi-vaults supported by substantial buttress vaults to create separate bathing chambers.

The subterranean hypocaust (a central heating system used throughout the empire to heat public buildings and elite homes) comprised three elements: 1) a wood burning furnace, 2) a floor raised on stacks of bricks and 3) rectangular terracotta heating flues. embed into the walls.

The building was incredibly energy efficient, facing the southwest to receive direct sunlight and incorporating glazed glass windows to trap heat. After the calderium water cooled, it was rechanneled to the tepidarium with some wastewater diverted to public toilets. Some waste water was also to power a grain mill located an underground chamber.

Although the building employed no new technologies or innovations, existing technology made it possible to rely on mainly (85%) skilled labor to to complete the building.

*See https://stuartbramhall.wordpress.com/2023/01/01/the-first-roads-in-the-ancient-world/

Film can be viewed free with a library card on Kanopy.

The Most Revolutionary Act

- Stuart Jeanne Bramhall's profile

- 11 followers