A Questionable Deterrent

In countries where the rule of law is less-than-robust, traffic cops can often best be classified as entrepreneurs rather than law-enforcement officials. Their main concern is not keeping the streets safe, but rather extracting bribes from unfortunate drivers—a pursuit that has made some Zambian policeman rather wealthy by that nation's standards:

Home Affairs Minister Kennedy Sakeni has wondered how a traffic officer can amass wealth worth K1 billion and yet his salary was only below K3 million. Mr. Sakeni says his office is aware that some of the officers make as much as K30 million per week which is never deposited into the government treasury but instead pocketed by themselves.

If my math is correct here, then, a Zambian traffic cop's actual income is approximately 333 times greater than his official income. So how can the government coax those police into giving up such filthy lucre, save for prosecuting each and every one to the fullest extent of the law?

The convenient answer is that the cops' salaries must be raised in order to reduce the temptation to extract bribes. But by how much? There is simply no way that the government can afford to replace all of the incomes that a cop would lose out on by going legit. How much of an increase will set a corrupt official on the straight-and-narrow?

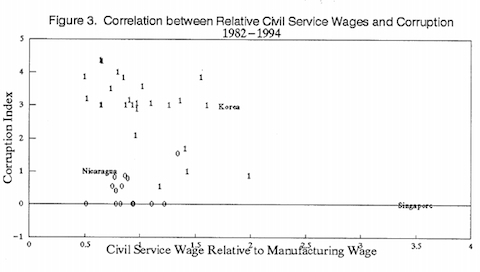

There is quite a bit of debate on this point. This landmark IMF paper from 1997 (PDF) suggests that a public-sector official's wages must be two to three times greater than that of his private-sector counterpart—a laughable proposition here in the U.S., of course, where civil-service salaries always lag. This case study from Tanzania (PDF), by contrast, concludes that even a massive salary bump doesn't always do the trick:

For a [revenue office] employee who is used to get bribes of TSh 20–30,000 daily, a tenfold increase of his salary from the present level will not make him desist from demanding and accepting bribes. The situation worsened even more due to the erosion by inflation of the initial pay rates for TRA staff, since nominal wages between 1996 and 2000 remained unchanged.

The ultimate solution probably has less to do with wages than with developing a sense of common purpose. But that's a slow fix that requires leadership by example. The lowliest official has no incentive to change his ways when the highest is taking suspiciously frequent ski vacations in Gstaad.