Answer: Does animal color and weight change by latitude?

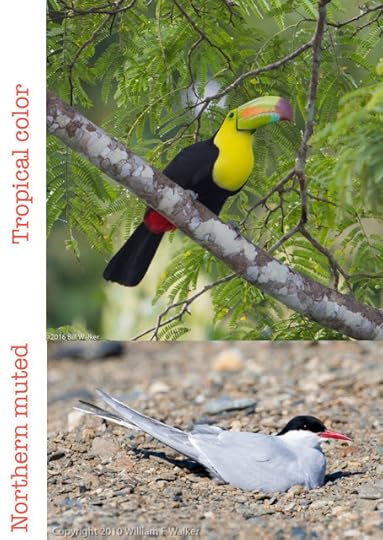

Colorful tropical birds...

Keel-billed Toucan in Belize, Arctic tern in Alaska.

Keel-billed Toucan in Belize, Arctic tern in Alaska. P/C William Walker © 2016, 2010 see: BirdWalker.com

Lead us to a mystery--don't tropical birds seem much more colorful than the birds that live closer to the poles?

Likewise, isn't there a tendency for animals to be different sizes if they're in the north vs. equatorial places?

Even more generally, are animals whose normal ranges are near the poles generally bigger than those whose normal ranges are more equatorial?

Or am I just hallucinating?

Last week's Challenge was to test these two hypotheses...

I began this investigation by posing this query:1. Is it true that birds have more brilliant colors near the equator, and are less colorful as you go farther north? If so, why would that be?

[ are equatorial birds more colorful than polar birds ]

which took me to an article in the British science journal NewScientist with the helpful title: Songbirds are more colourful the closer they live to the equator. The subtitle gives us a hint: "Computer analysis has shown that 19th-century naturalists including Charles Darwin were right: birds near the equator are more colourful."

Game over? Maybe, but I always recommend digging a little deeper to understand why. The idea that tropical birds are more colorful was first introduced by 19th-century naturalists such as Charles Darwin and Alexander von Humboldt (who we have discussed before in SRS--see Leaping Eels, and the Great Man Theory).

Until recently, however, it has been hard to prove this hypothesis due to difficulty in quantifying the colors of birds. Just looking at a few birds and observing "yeah, tropical toucans are colorful, but my local northern sparrows are drab" doesn't cut it. What we want is some kind of broad-based analysis. We are, after all, trying to see if "birds (generally speaking) have more brilliant colors near the equator."

Luckily, Chris Cooney (U. Sheffield) tested the idea on songbirds (specifically, the Passeriformes, which are about 60 per cent of all bird species).

Now, equipped with more advanced color analysis methods, Cooney's group found that, yes indeed, songbirds that live in equatorial climates ARE more colorful than their temperate climate cousins.

What's more, birds in forests are more colorful than those that don't live in forests.

You should also know that the journal New Scientist is a kind of digest of science news. They always provide a link to the original paper that they're summarizing, which in this case leads to Cooney et al.'s paper Latitudinal gradients in avian colourfulness, published in Nature Ecology and Evolution. In this paper you can read all of the details of HOW they measured color (and why it's harder than you think), along with the killer plot of color by latitude:

Bird colorfulness by lattitude. Redder is "more diversity in colors" while bluer is less diverse. Adapted from Figure 2 in Cooney et al.' paper (see above).

Bird colorfulness by lattitude. Redder is "more diversity in colors" while bluer is less diverse. Adapted from Figure 2 in Cooney et al.' paper (see above).Of course, I want to check another source for agreement about the color hypothesis, so I did another search in Google Scholar, using some of the terms I picked up while reading Cooney's work. My search there was for:

[ bird color variation by latitude ]

Turns out there are lots of paper on this topic! I skimmed a bunch and found that this color-by-latitude idea has been debated widely over the years, with some papers showing true variations, while others don't. The key difference in the findings seems to be the sample size and the method researchers used to measure color. See Cooney's paper again--it's a hard problem! And, generally speaking, small studies (with less latitude variation) tended to NOT find color differences. You need a big sample to see the effect.

But as I skimmed, I noticed several references to a "rule" that described color variation by latitude. So my next query was:

[ rule describing bird color change by latitude ]

Voila! I discovered Golger's Rule which is

"...an ecogeographical rule that links animal colouration with climatic variation. This rule is named after C.W.L. Gloger who was one of the first to summarise the associations between climatic variation and animal colouration, noting in particular that birds and mammals seemed more pigmented in tropical regions." (From: Delhey, Kaspar. "Gloger’s rule." Current Biology 27.14 (2017): R689-R691.)

Fascinating. Golger's rule is really about the total amount of pigmentation, but it extends to color pigments as well. This color-variation-by-latitude seems to be much more than just birds, although it's pretty clear that birds DO vary by latitude, with brilliant colors being more tropically inclined.

2. Is it true that the closer an animal species is to the poles, the larger they are? Again, if so, why?

Taking the lessons I learned from the bird/color Challenge, my first query was in Google Scholar:

[ latitudinal variation in animal body size ]

Which produced a wealth of insights, particularly around a rule that's similar to Golger's Rule, but for animal body size rather than pigment or color. Bergmann's rule (1847) was originally written as “Within species and amongst closely related species of homeothermic animals a larger size is often achieved in colder climates than in warmer ones, which is linked to the temperature budget of these animals.”

That is, within a clade ("closely related species"), it's generally true that the closer an animal lives to the equator, the smaller it will be.

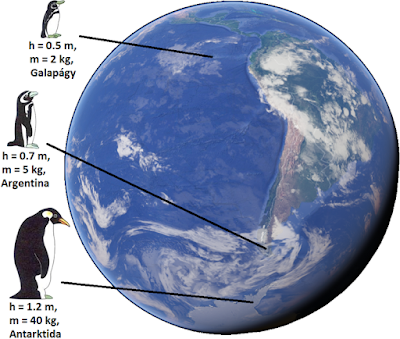

Bergmann's rule can be summarized by this diagram (which just happens to be of a bird):

Bergmann's rule for penguins--the more equatorial the animal within its clade,

Bergmann's rule for penguins--the more equatorial the animal within its clade,

the smaller it is. P/C Wikimedia.

Which is a remarkable result! But, as you'd expect, in the intervening 175 years, some exceptions have been found (including some frogs that show the opposite of Bergmann's rule and howler monkeys that are inverse Bergmann's within a limited range), and the rule has been amended for special conditions (birds, and measurements of size). However, in general, the rule seems to hold. For details, see this authoritative article: Geographic gradients in body size: a clarification of Bergmann's rule. (Blackburn, Tim M., Kevin J. Gaston, and Natasha Loder. "Geographic gradients in body size: a clarification of Bergmann's rule." Diversity and distributions 5.4 (1999): 165-174.)

So, yes, birds ARE more colorful near the equator (in general) AND animals are smaller near the equator (in general). Which partly explains the plethora of beautiful hummingbirds in the jungle. But let's talk about what SRS insights we should take away from this Challenge.

1. Straight-forward questions are often a great starting tactic. The ability of search engines to understand what you mean with a question like our first query [ are equatorial birds more colorful than polar birds ] is improving all the time. With a good start, we can begin to dive more deeply into the real content.

2. Double check by doing a different query to get a the same idea. In this case, my second and third queries were restatements of the original query, but using somewhat different language. Those new terms were learned from what I was reading. That is...

3. Learn new terms as you read in the area. This is one of the more important SRS lessons: learn as you read. In particular, when you see a word or phrase that's new to you, be sure to look it up--you might be able to make your next query much more focused with the language and ideas you pick up along the way.

4. Notice ideas as you read. More than just language and terminology, you want to also notice ideas as your doing your research. While I was searching for birds and color, I noticed the use of a "rule" to describe the latitudinal variations. That was incredibly effective when I went to search for size variability--it turns out that biologists love to express relationships as "rules." That's an idea I'll carry forward for the next time I have to search for something like this.

Hope you enjoyed the Challenge!

Search on!