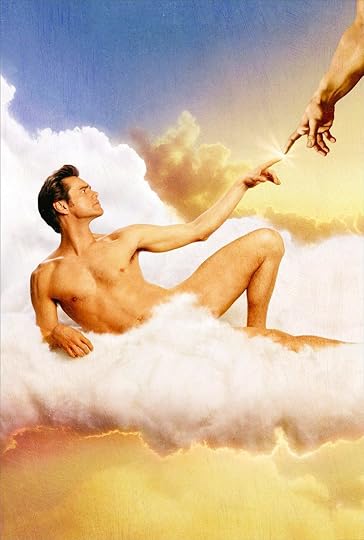

Cur Deus Homo?

Sorry for not having updated things in so long, I have been traveling a lot. Those tornadoes in Dallas last week? Suffice it to say I was severely inconvenienced. I may not have lost my home and all my worldly possessions, but still.

Sorry for not having updated things in so long, I have been traveling a lot. Those tornadoes in Dallas last week? Suffice it to say I was severely inconvenienced. I may not have lost my home and all my worldly possessions, but still.I have been following with serious fascination the discussion about Nestorianism over at Green Baggins (as I'm sure you have too, for nothing catches the attention of the masses like fourth-century christological heresies and their relevance for today). I'll bring you up to speed on the issue and then make an observation or two.

The Chalcedonian understanding of the communicatio idiomatum (communication of properties) says that what can be predicated of either of Christ's natures may be said of his Person as a whole. For example, Jesus, being a divine Person who assumed human flesh, can suffer upon the cross according to his human nature (since the divine nature is impassible) and it can truly be said that the divine Son suffered and died. This is why the church affirmed Mary as the theotokos (God-bearer): Though she was not the source of the Son's divine nature but his human nature, she indeed gave birth to a Person and not a mere nature, and that Person is divine.

The question has now turned to how exactly, if Christ is only a divine Person, the properties of his humanity can be communicated to his Person (comment #74).

To take a slight turn off-course, I can't help but think that such a discussion dovetails with the issue of theosis, or divinization. If the issue of the communication of properties arises from a consideration of the incarnation, then the question arises, "Why did the Son of God assume human flesh in the first place?" If salvation entailed only the canceling of debt and imputation of righteousness, could there have been some other way to accomplish it besides the incarnation of the divine Logos? If the answer is yes (that conceivably God could have found another way to accomplish this), then it must mean that our salvation involves more than the cancellation of debt and the imputation of righteousness. Otherwise, why go to such lengths?

The early church fathers would have answered the question "Why the God-Man?" by insisting that the Son assumed our nature so that we could participate in his -- that "he became man so that we could become God," to borrow Augustine's formula. It is here that the debates about the communicatio idiomatum cease to be theoretical and become not only practical, but sublime. The apostle John insists that since we are children of God (and since fathering children in their likeness is what fathers do), we shall be "like him, for we shall see him as he is" (I John 3:1ff).

Thus while the current debates over how the natures of Christ relate to his Person deal specifically with how the Bible allows us to speak of Jesus, the end result of the incarnation is anything but merely stipulative, predicative, or declarative, but is much more than that.

God doesn't just say stuff about us that isn't really true, but he makes us to be what he in his grace declares, is what I'm saying.

Published on April 10, 2012 20:19

No comments have been added yet.

Jason J. Stellman's Blog

- Jason J. Stellman's profile

- 5 followers

Jason J. Stellman isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.