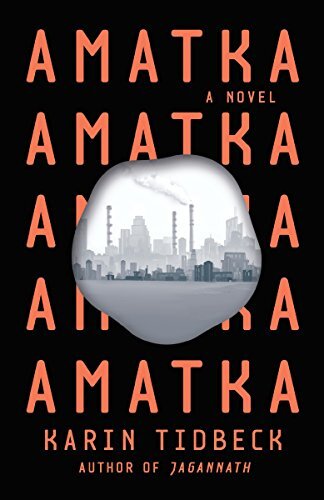

Book Reviews: Cool Idea, Confusing Bummer Ending

Book description: “Vanja, an information assistant, is sent to the austere, wintry colony of Amatka to collect marketing information. Intending to stay just a short while, she falls in love with her housemate and prolongs her visit. But when she stumbles on evidence of a growing threat to the colony and a cover-up by its administration, she embarks on an investigation that puts her at tremendous risk.”

Book description: “Vanja, an information assistant, is sent to the austere, wintry colony of Amatka to collect marketing information. Intending to stay just a short while, she falls in love with her housemate and prolongs her visit. But when she stumbles on evidence of a growing threat to the colony and a cover-up by its administration, she embarks on an investigation that puts her at tremendous risk.” Told through deceptively simple prose, Karin Tidbeck’s Amatkadepicts a world chillingly reminiscent of George Orwell’s 1984. Layers of bureaucracy and social conditioning create the illusion of a happy community, while despair, disease, and alienation produce attrition and threaten the city’s survival. Social and psychological disintegration parallel the breakdown of the physical environment. Objects large and small must be constantly marked with written labels or names spoken aloud or they break down into amorphous goo.

The use of language in creating and maintaining reality is one of the more creative I’ve seen. I admired how Tidbeck introduces her world with very little explanation, using subtle clues layered into the otherwise prosaic action. For most of the book, I had a pretty good idea of what was going on: the mutable nature of matter, the increasing suppression of dissent, the enforcement of conformity, and the inexorable loss of history. I was curious about how humans had come to live in a world in which the basic rules of physics were so plastic and what the underground resistance was about, but I was also confident that the answers would be made clear.

The publisher describes this book as, “A surreal debut novel set in a world shaped by language in the tradition of Margaret Atwood and Ursula K. Le Guin.” The only part of this description I agree (other than “debut”) with is “surreal.” Atwood and Le Guin created imaginative, provocative stories, but their work is accessible to most readers. There’s a difference between being mysterious and mystifying. As I waited for the answers to the many questions Tidbeck raised, she piled mystifying upon mystifying until I had no idea what exactly Vanja was discovering (other than that the commune was re-using stable “good” paper for announcements).

The book ends with Vanja acting in an erratic, destructive manner, setting fire to the records she previously treasured, and then being lobotomized so that when she’s freed, she no longer possessed the speech that would allow her to re-shape the world as part of the resistance. I don’t mind grimness, but such a downer puts Amatkasquarely in the 1984 camp. This could have been such a cool book, too, with a denouement that made all the sacrifices worth it. After earning my trust as a reader, Tidbeck dropped the ball royally. I doubt I’ll pick up anything of hers in the future. To be fair, however, I don’t think the disappointing ending is entirely Tidbeck’s fault; it’s what happens when pretentious literary editors take on genre projects.