How to Understand Crime Writing by Irish Academics in the Context of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse

Declan Burke's Crime Always Pays blog sets out to educate the reader both about Irish Crime Fiction and his own work, the most recent examples of which are Absolute Zero Cool and Crime Always Pays

. Along the way, the blog can show up gaping holes in the reader's philosophical and religious knowledge that may persuade him/her to buy a book miles removed from Irish crime writing. I have an example from today.

. Along the way, the blog can show up gaping holes in the reader's philosophical and religious knowledge that may persuade him/her to buy a book miles removed from Irish crime writing. I have an example from today.Declan Burke's post about Matt McGuire's debut novel, Dark Dawn - Killing in Cold Light, revealed that this author is in the employ of the University of Western Sydney. The post drew an implicit comparison with Rob Kitchin, the author of The Rule Book, which I enjoyed reading a few weeks ago. Rob Kitchin runs the excellent Crime Fiction blog The View from the Blue House, and also works at the University of Maynooth in Ireland.

Declan's beginning to the end of his blog post was, "So there you have it. Yet more academic professor-types writing Irish crime fiction. Which is, surely, the literary equivalent of the second horse of the apocalypse."

That comment brought home to me the unwelcome truth that, although I've had the occasional brush with academia, I knew next to nothing about the second horse of the Apocalypse and its rider and why the author of Absolute Zero Cool drew that comparison. In the effort to educate myself, my first port of call was Wikipedia, where I learned the second horse is often associated with "civil war". So that neatly explained its use in the context of the wider academic community. However, most of the rest of my education about the Book of Revelations comes entirely from listening to Johnny Cash's song When the Man Comes Around and Johnny never went into any depth about the four horses.

If I wished to continue reading blogs about Irish academics writing Crime Fiction I would need to brush up on my knowledge of the New Testament.

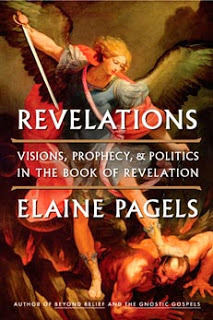

Luckily, I had a copy of the New York Review of Books on my lap (under the laptop), open at the review of Elaine Pagels' Revelations: Visions, Prophecy, and Politics in the Book of Revelation[image error]. Here's the excerpt that gave me the insight Elaine Pagels' book could provide me with the appropriate level of Apocalyptic knowledge:

"Just about the only chronological indicator in Revelation on which most interpreters agree is the mystic number of the beast that appears from the earth in succession to a fearful creature from the sea with seven heads and ten crowned horns. Both beasts represent the enemies of John and his religion. The seven heads represent seven kings, "of whom five have fallen, one is living, and the other has not yet come." The second beast, "that was and is not," stands for an eighth king who will remain for only a little while, and he is explicitly described as one of the seven kings. He is named by the number 666. When this number is converted into Hebrew letters, each of which can carry a numerical value, the name of the emperor Nero emerges. This is perhaps the only gloss on the text of Revelation for which there is a substantial scholarly consensus. John's description of seven kings, of whom five have fallen, fits perfectly the five emperors from Augustus to Nero. The one who is living and the other yet to come point in turn to Galba, who reigned for six months, and to his successor Otho."

In an interview with ExpressNight, It Isn't the End of The World I found a very nice photograph of Elaine Pagels and an interview with her that put a seal on my decision to buy the book:

"Primarily, I say this book is an indictment of the Roman Empire by a prophet [John of Patmos] who's living in a dangerous time," says Pagels. "[Disciples] Peter was crucified, Paul was beheaded — the leaders of this movement are being killed by representatives of the Roman Empire. So John writes a prophetic denunciation of Rome saturated with the language of classical prophets."

That language, though, has made Revelation wide open to interpretation. "The language is vivid, but not specific," says Pagels. "Because it's written in visionary language, it can be read in many ways. The plot is 'evil forces have taken over the world, and God is going to return and His justice will be served.' If you're having a conflict with people you see as being opposed to you, you can read yourself into that story."

And people have read themselves into that story since the time it was written. "You can read it in the 11th century, and it was against the 'infidels' and it justified the First Crusade. You can read it in the 14th and 15th centuries, and Protestants read it against Catholics and Catholics read it against Protestants." In the American Civil War, the Northern "Battle Hymn of the Republic" used imagery from the Book of Revelation: A winepress that would squish the "grapes of wrath" and a sword both appear in Revelation, and the allusions get even more pronounced in later verses. And during WWII, Dr. Seuss himself drew political cartoons depicting Hitler as the Great Beast mentioned in the book.

Taking John of Patmos' images and bending them for social or political meanings doesn't bother Pagels. "That's how the book survived," she says. "Many people living in oppression saw it as a book about God's justice. The openness of the symbols lends it to that. I'm not shocked that they do that."

Published on April 09, 2012 14:10

No comments have been added yet.