ÎÏλÏÏ ÏÏλαÏÏÎ¿Ï Î»Î¿Î¹ÏÏν ο ÎÎνιοÏ...

ÎÏλÏÏ ÏÏλαÏÏÎ¿Ï Î»Î¿Î¹ÏÏν ο ÎÎÎ½Î¹Î¿Ï Î' (καθ' Î·Î¼Î¬Ï ÎγαμÎμνÏν ..)ΥΠΠÎÎ ÎÎÎΡÎÎΣÎÎΣÏο ÏαÏÏν Î' μÎÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏολιαÏÎ¼Î¿Ï Î¼Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î²Î¹Î²Î»Î¯Î¿Ï ÎμηÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÎναÏολή ÏÏο ÏÏÎ±Ï ÏοδÏÏμι ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ¹Î³Î±Î¯Î¿Ï , ÎÏÏοÏία, ÎÏÏαιολογία, ÎÏ Î¸Î¿Î»Î¿Î³Î¯Î± θα εÏικενÏÏÏθοÏμε Ïε θÎμαÏα κοÏμογονίαÏ, Î¸ÎµÎ¿Î³Î¿Î½Î¯Î±Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ εν γÎνει θÏηÏÎºÎµÏ Ïικά - Î¼Ï Î¸Î¿Î»Î¿Î³Î¹ÎºÎ¬.

Î' Î ÎΡÎΤÎΡÎΣÎ

ΣÏην Ïελ. 17 ο ΧανιÏÏÎ·Ï Î±Î½Î±ÏÎÏεÏαι ÏÏην ÏÏÎÏη ÏÎ¿Ï Î¼ÏÎ¸Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏ Î»Î»Î¹ÎºÎ¿Ïμμη με Ïον μÏθο ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏιλλÎα, ÏαÏαÏÎμÏονÏÎ±Ï Ïε αÏÏÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÏÎ·Ï Bachvarova και άλλÏν, οι οÏÎ¿Î¯ÎµÏ Î±ÏÎ¿Î´Î¯Î´Î¿Ï Î½ ÏαÏακÏηÏιÏÏικά ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏιλλÎÏÏ Î±Î»Î»Î¬ και ÎμηÏικά ÏÏοιÏεία, άν ÏÏι Ïλον Ïον εÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÎºÏκλο (;),[1] Ïε εξ ÎναÏολÏν εÏιÏÏοή (ex oriente lux) ... .. Î¥ÏÎµÎ½Î¸Ï Î¼Î¯Î¶Î¿Ï Î¼Îµ ÎµÎ´Ï ÏÏι η Bachvarova, εξεÏάζονÏÎ±Ï Ïην ÏÏοÎÎ»ÎµÏ Ïη ÏÎ·Ï ÎμηÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎλιάδαÏ, καÏαλήγει Ïελικά ÏÏο ÏÏ Î¼ÏÎÏαÏμα ÏÏι οι ÏÏÏÏοι ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½ÎµÏ Î¬Ïοικοι ÏÏην ÏεÏιοÏή ÏÎ·Ï Î¤ÏÏÎ¬Î´Î±Ï Î²Ïήκαν εκεί μιαν ήδη καθιεÏÏμÎνη, γηγενή ÎναÏολιακή ÏαÏάδοÏη για Ïην ÏÏÏÏη ÏÎ·Ï Î¤ÏοίαÏ, Ïην οÏοία ÏÏη ÏÏ Î½ÎÏεια ÏÏοÏάÏμοÏαν. ÎÏ Ïή η Î³Î·Î³ÎµÎ½Î®Ï ÏαÏάδοÏη διαμοÏÏÏθηκε - καÏά Ïην ίδια ÏάνÏα - αÏÏ ÏÎ¹Ï ÏαÏαδÏÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎγγÏÏ ÎναÏÎ¿Î»Î®Ï Î¼Îµ Ïην μεÏολάβηÏη ÏÎ·Ï Î±Ï ÏοκÏαÏοÏÎ¯Î±Ï ÏÏν ΧεÏÏαίÏν. Î Bachvarova αναÏÏÏÏÏει μια λεÏÏομεÏή ÏÏÏÏμαÏογÏαÏία ÏÎ·Ï ÎλιάδαÏ, ÏÎ¿Ï ÏεÏιλαμβάνει μια ÏÏÏιμη Î»Î¿Ï Î²Î¹ÎºÎ® 'Wilusiad', μια μεÏαγενÎÏÏεÏη ΦÏÏ Î³Î¹ÎºÎ® ÏαÏάδοÏη για Ïην ÏÏÏÏη ÏÎ·Ï Î¤ÏοίαÏ, διάÏοÏÎµÏ ÏιθανÎÏ ÎµÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¿ - αναÏολιακÎÏ Î´Î¯Î³Î»ÏÏÏÎµÏ ÏαÏαδÏÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ Ïον ανÏαγÏνιÏÎ¼Ï Î¼ÎµÏÎ±Î¾Ï ÎιολÎÏν και ÎÏνÏν αοιδÏν ÏÏην ÎναÏολία. ÎÏ ÏÏ ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ Îνα ÏÏνθεÏο Ï ÏÏδειγμα, ÏÎ¿Ï Î¼ÏοÏεί να αμÏιÏβηÏηθεί Ïε οÏιÏμÎÎ½ÎµÏ Î»ÎµÏÏομÎÏειεÏ, αλλά η ÏÏαγμαÏικÏÏηÏα ÏÏÎÏει - καÏά Ïον Elmer ÏÏην ÏÏεÏική βιβλιοκÏιÏία ÏÎ¿Ï - ÏÎ¯Î³Î¿Ï Ïα να ήÏαν ÏÎ¿Ï Î»Î¬ÏιÏÏον Ïο ίδιο ÏεÏίÏλοκη, αν ÏÏι ÏεÏιÏÏÏÏεÏο...[2]

Î ÏάγμαÏι ÎÏει διαÏιÏÏÏθεί ÏÏι αÏκεÏÎÏ Î±ÏηγημαÏικÎÏ Î»ÎµÏÏομÎÏÎµÎ¹ÎµÏ ÎµÎ¼ÏανίζονÏαι με ÏαÏÏμοιο ÏÏÏÏο ÏÏÎ¹Ï ÏαÏαλλαγÎÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î¸ÎμαÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎαÏÎ¹Î»ÎµÎ¯Î±Ï ÏÏον ÎÏ ÏÎ±Î½Ï (Kingship in Heaven) ÏÎ¿Ï Î¤ÏÎ±Î³Î¿Ï Î´Î¹Î¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎναδÏÏεÏÏ (Song of Going Forth)[3] και ÏÏην Îεογονία: οι ÏÏλοι ÏÏν βαÏιλÎÏν ÏÏον Î¿Ï ÏÎ±Î½Ï (Anu/ÎÏ ÏανÏÏ, Kumarbi/ÎÏÏνοÏ, ÎεÏÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÎºÎ±ÏÎ±Î¹Î³Î¯Î´Î±Ï (stormgod)/ÎεÏÏ), ο ÎµÏ Î½Î¿Ï ÏιÏμÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Anu/ÎÏ ÏÎ±Î½Î¿Ï ÏÏαν είÏε Ïην ÏÏÏÏοκαθεδÏία ÏÏν θεÏν, η ÏαÏÎ¿Ï Ïία ÏλήÏÏÏ Î±Î½ÎµÏÏÏ Î³Î¼ÎνÏν θεÏν μÎÏα ÏÏον Kumarbi/ÎÏÏνο καθÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ η ÏÏοÏή με Î»Î¯Î¸Î¿Ï Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ η εκÏÏÏμιÏή ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïον Kumarbi/ÎÏÏνο, οι οÏοίοι ÏÏην ÏÏ Î½ÎÏεια καθίÏÏανÏαι ανÏικείμενο ÏεβαÏμοÏ.[4]

ÎμÏÏ Î¿Î¹ ομοιÏÏηÏÎµÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏαÏαλληλιÏμοί[5] οι οÏοίοι ÏÏάγμαÏι ενÏοÏίζονÏαι ÏÏην θεογονία λαÏν ÏÎ·Ï ÎναÏÎ¿Î»Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎεÏÎ¿Î³ÎµÎ¯Î¿Ï Î±ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Beckman & Arbor αÏοδίδονÏαιÏÏην ÏÏαÏξη Î¼Î¹Î¬Ï Î Î¿Î»Î¹ÏιÏÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎÎ¿Î¹Î½Î®Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÏεÏιοÏÎ®Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÏι Ïε μεÏάδοÏη ÏÏοÏÏÏÏν ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½ÎµÏ Î¼ÎÏÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÎναÏολίαÏ![6]

[image error] ÎξÏÏÏ Î»Î»Î¿ ÏÎ¿Ï Î²Î¹Î²Î»Î¯Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Burkert[7]

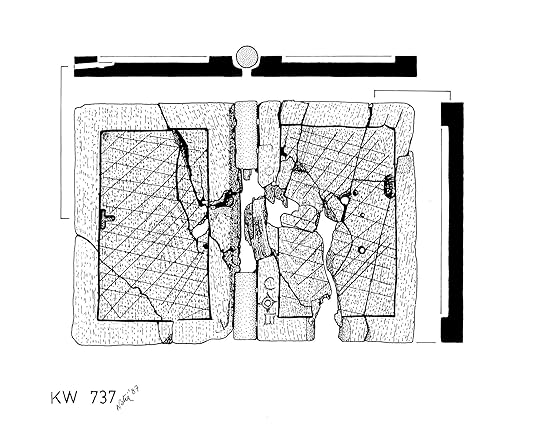

Î Burkert αναλÏγÏÏ Ï ÏοÏÏηÏίζει (αναÏεÏÏÎ¼ÎµÎ½Î¿Ï ÏÏην αÏÏαÏκή ÏεÏίοδο):[8].. ÏÏην οÏοία, Ï ÏÏ Ïην εÏιÏÏοή ÏÎ·Ï ÏημιÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎναÏÎ¿Î»Î®Ï â αÏÏ ÏÏ Î³Î³ÏαÏείÏ, ÏεÏνίÏεÏ, εμÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï, θεÏαÏÎµÏ ÏÎÏ â ο ελληνικÏÏ ÏολιÏιÏμÏÏ Î¬ÏÏιÏε Ïη μοναδική ÏÎ¿Ï Î¬Î½Î¸Î·Ïη, για να αÏοκÏήÏει ÏÏνÏομα Ïην ÏολιÏιÏÏική ηγεμονία ÏÏη ÎεÏÏγειο (.. which, under the influence of the Semitic Eastâfrom writers, craftsmen, merchants, healersâGreek culture began its unique flowering, soon to assume cultural hegemony in the Mediterranean). ÎμÏÏ ÏÏοιÏείο ιÏÏοÏÎºÎµÏ Î®Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÏιβληÏικά κοÏμεί Ïο εξÏÏÏ Î»Î»Î¿ ÏÎ¿Ï Î²Î¹Î²Î»Î¯Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏαÏακÏηÏίζεÏαι αÏÏ Ïον ίδιο ÏÏ 'βÏÏειο Î£Ï ÏιακÏ' αÏοδεικνÏεÏαι ÏÏι δεν ÏÏεÏείÏαι ÎνÏÎ¿Î½Î·Ï ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÏÏ ÏÏεÏίÏεÏÏ, Ï ÏονομεÏονÏÎ±Ï ÎÏÏι αÏÏ Ïην αÏÏή Ïην εÏιÏειÏημαÏολογία ÏÎ¿Ï ! Î£Ï Î³ÎºÎµÎºÏιμÎνα Ïο εÏÏημα ÏÏοÎÏÏεÏαι αÏÏ Ïο ÎÏαίον Î£Î¬Î¼Î¿Ï , ÏÏ Î»Î¬ÏÏεÏαι δε ÏÏο ÎÎ¿Ï Ïείο ÎαÏλοβαÏÎ¯Î¿Ï .[9] Î ÏÏκειÏαι για ÏÏομεÏÏÏίδιο ίÏÏÎ¿Ï , ενδεÏομÎνÏÏ Î»Î¬ÏÏ Ïο ÏÏοεÏÏÏμενο αÏÏ Ïην εκÏÏÏαÏεία ÏÏν ÎÏαμαίÏν ενανÏίον ÏÎ·Ï ÏολιÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï Î¿Î½ÏÏÏηÏÎ¿Ï Patina/Unki, Ï Î²ÏÎ¹Î´Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÏÎ»Î·Î¸Ï ÏÎ¼Î¹Î±ÎºÎ®Ï ÏÏ ÏÏάÏεÏÏ, ÏεÏÎ¹Î»Î±Î¼Î²Î¬Î½Î¿Ï ÏÎ±Ï Î¹ÏÏÏ ÏÏ ÎÎ¹Î³Î±Î¹Î±ÎºÏ (ÎλληνικÏ) ÏÏοιÏείο. Î Palastin (Walastin εκ ÏÎ¿Ï Î¦Î¹Î»Î¹ÏÏαίοÏ) Ï ÏήÏξε μεγάλο και ιÏÏÏ ÏÏ Î¦Î¹Î»Î¹ÏÏαÏÎºÏ Î²Î±Ïίλειο ÏÏην Ïεδιάδα Amuq καÏά Ïο ÏÎÎ»Î¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï Î´ÎµÏ ÏÎÏÎ±Ï ÏιλιεÏÎ¯Î±Ï Ï.Χ. και μεÏά, Ïο οÏοίο ήλεγÏε Ïο ÏημανÏÎ¹ÎºÏ Î¸ÏηÏÎºÎµÏ ÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÎºÎνÏÏο ÏÎ¿Ï Aleppo και Ïην ÏεÏιοÏή ÏÎ·Ï Hama, ÏεÏιλαμβάνονÏÎ±Ï ÏÎ¹Ï Patina/Unqi, Arpad και Hamath, γνÏÏÏÎÏ ÏολιÏικÎÏ Î¿Î½ÏÏÏηÏÎµÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏοÏÎ®Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î£Î¹Î´Î®ÏÎ¿Ï .[10]Î Î¯Î´Î¹Î¿Ï ÎλλανδÏÏ ÎµÏÎµÏ Î½Î·ÏÎ®Ï ÎµÎ½ÏοÏίζει ομοιÏÏηÏα μεÏÎ±Î¾Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎÎ´Ï ÏÏÎµÎ¹Î±ÎºÎ®Ï ÏÎºÎ·Î½Î®Ï ÏÏÎ¿Ï Î· ΠηνελÏÏη Ïηγαίνει ÏÏην Ï ÏεÏÏα ÏÏοκειμÎÎ½Î¿Ï Î½Î± ÏÏοÏÎµÏ Ïηθεί ÏÏην Îθηνά εν ÏÏει ÏÎ·Ï Î±Î½Î±ÏÏÏήÏεÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î¤Î·Î»ÎµÎ¼Î¬ÏÎ¿Ï , Od. 4. 759-767, και ÏÎ·Ï ÏÎºÎ·Î½Î®Ï ÏÏην Î¤Ï Ïική ÎκδοÏη ÏÎ¿Ï Gilgamesh,[11] ÏÏÎ¿Ï Î· Ninsun, μηÏÎÏα ÏÎ¿Ï Gilgamesh, ÏÏοβαίνει ÏÏην ίδια ÏÏάξη ανεÏÏÏμενη ÏÏην οÏοÏή, εν ÏÏει ÏÎ·Ï Î±Î½Î±ÏÏÏήÏεÏÏ ÏÏν Gilgamesh και Enkidu για Ïο εÏÎ¹ÎºÎ¯Î½Î´Ï Î½Î¿ Ïαξίδι ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ïον Humbaba.[12] Îνάλογη ÏÏοÏÎγγιÏη Î±ÎºÎ¿Î»Î¿Ï Î¸ÎµÎ¯ ο Burkert αναÏεÏÏÎ¼ÎµÎ½Î¿Ï ÏÏην καÏ' Î±Ï ÏÏν ειÏαγÏμενο ÎÏÏλλÏνα[13] αλλά ÏÏον θÏÏλο ÏÏν ÎÏÏά εÏί ÎÎ®Î²Î±Ï Ïον οÏοίον αÏοδίδει Ïε ÎεÏοÏοÏαμιακή εÏίδÏαÏη αÏÏ Ïον ÏοιηÏή Kabti-Ilani-Marduk ÏÎ·Ï ÏÎµÎ»ÎµÏ ÏÎ±Î¯Î±Ï ÏιλιεÏÎ¯Î±Ï Ï.Χ.,[14] άν και οι ÎλληνικÎÏ ÎμηÏικÎÏ Î±Î½Î±ÏοÏÎÏ Î¸ÎµÏÏοÏνÏαι αναγÏÎ¼ÎµÎ½ÎµÏ Ïε ÏÏÏÏεÏο ÏÏÏνο! Î Ïίν κλείÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Îµ Ïην αναÏοÏά Î¼Î±Ï ÏÏÎ¹Ï Î¸ÎÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Burkert ÏημειÏÎ½Î¿Ï Î¼Îµ Ïην άÏοÏή ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏι οι ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½ÎµÏ Î±Î½ÎÏÏÏ Î¾Î±Î½ ÏÏι Î±Ï Ïοί δανείÏÏηκαν αÏÏ Ïην ÎναÏολή, Ï ÏοÏÏηÏίζονÏÎ±Ï ÏÏι ÏλείÏÏα Îλληνικά ÏεÏÎ½Î¿Ï ÏγήμαÏα ÏÎ·Ï ÎναÏÎ¿Î»Î¯Î¶Î¿Ï ÏÎ±Ï ÏεÏιÏÎ´Î¿Ï Î¼ÏοÏοÏν καλλίÏεÏα να εÏÎ¼Î·Î½ÎµÏ Î¸Î¿Ïν ÏÏ ÎÏγα μεÏαναÏÏÏν αÏÏ Ïην ÎναÏολή, ÎµÎ½Ï Î´Î¹Î±ÏÏ ÏÏνει και Ïην ανιÏÏÏÏηÏη άÏοÏη ÏÏι οι ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½ÎµÏ Îμαθαν για ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÎ¯Î½Î±ÎºÎµÏ Î³ÏαÏÎ®Ï Î±Î»Î»Î¬ και ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î´ÎµÏμάÏÎ¹Î½Î¿Ï Ï ÎºÏ Î»Î¯Î½Î´ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïην ίδια ÎναÏολή,[15] αγνοÏνÏÎ±Ï Ïο ÏαÏελθÏν ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÏο Îιγαίο ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏοÏÎ®Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î§Î±Î»ÎºÎ¿Ï![16] Î ÏάγμαÏι ÏÏην ÎÏαμμική Î ÏÏ Î½Î±Î½ÏοÏμε Ïην λÎξη di-pte-ra-po-ro, ήÏοι διÏθεÏαÏÏÏοÏ, ÎµÎ½Ï ÏÏο ÎÏ ÎºÎ·Î½Î±ÏÎºÎ®Ï ÏÏ ÏÏεÏίÏεÏÏ Î½Î±Ï Î¬Î³Î¹Î¿ ÏÎ·Ï ÎνÏιÏÎÎ»Î»Î¿Ï (Uluburun) ÎÏÎ¿Ï Î½ Î±Î½ÎµÏ Ïεθεί ξÏÎ»Î¹Î½ÎµÏ ÏÏÏ ÎºÏÎÏ ÏÎ¹Î½Î±ÎºÎ¯Î´ÎµÏ Î³ÏαÏήÏ, η μία μάλιÏÏα ÏÎÏÎ¿Ï Ïα αÏιθμηÏικά ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏαμμικήÏ![17] ΣÏο ίδιο ÏνεÏμα ο ÏÏ Î³Î³ÏαÏÎÎ±Ï Î±Ïοδίδει ΣημιÏική καÏαγÏγή ÏÏην λÎξη δÎλÏοÏ, αγνοÏνÏÎ±Ï Ïην εναλλακÏική ÏÏ ÏÏÎÏιÏη με Ïο δαιδάλλÏ![18]

Το 'ÏÏÏÏο βιβλίο ÏοÏ

κÏÏμοÏ

' αÏÏ Ïο ναÏ

άγιο ÏÎ·Ï ÎνÏιÏÎλλοÏ

Το 'ÏÏÏÏο βιβλίο ÏοÏ

κÏÏμοÏ

' αÏÏ Ïο ναÏ

άγιο ÏÎ·Ï ÎνÏιÏÎλλοÏ

Îίναι Î½Î¿Î¼Î¯Î¶Î¿Ï Î¼Îµ ενδιαÏÎÏον να ÏημειÏÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Îµ ÎµÎ´Ï ÏÏι η Bachvarova θεÏÏεί ÏÏι Ïα αÏηγημαÏικά ÏÏαγοÏδια ÏÎ·Ï Î§Î¿Ï ÏÎ¹Î±Î½Î®Ï - ΧεÏÏιÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÏαÏαδÏÏεÏÏ Ï ÏήÏξαν ÎÏγα ÏÎ·Ï Î»ÎµÎ³Î¿Î¼ÎÎ½Î·Ï ÏÏοÏοÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÏαÏαδÏÏεÏÏ, με Ïην ÏειÏά ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î´Îµ ÏÏ ÏÏεÏίζονÏαι ÏÏενά με Ïην ÏαÏάδοÏη ÏÎ·Ï ÎγγÏÏ ÎναÏολήÏ. ÎαÏά Ïην ίδια η ÏαÏάδοÏη καÏÎÏÏη διαθÎÏιμη - γνÏÏÏή ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î±Î³ÏαμμάÏÎ¿Ï Ï[19] ÎλληνÏÏÏÎ½Î¿Ï Ï[20] αοιδοÏÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏοÏÎ®Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î£Î¹Î´Î®ÏÎ¿Ï Î¼ÎÏÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏοÏοÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎµÎºÏοÏÎ¬Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÏιθανÏÏ ÏÏο ÎδαÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎναÏÎ¿Î»Î¯Î±Ï ÎºÎ±Ïά ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î±Î¹ÏÎ½ÎµÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÏÎµÎ»ÎµÏ ÏÎ±Î¯Î±Ï Ï.Χ. ÏιλιεÏίαÏ..[21].

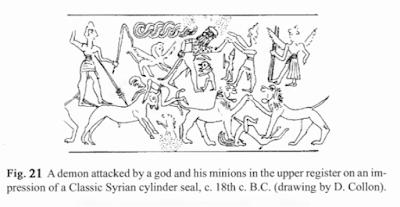

ÎÏÏÏμενοι ÏÏα Ï ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¸Î·Î³Î·ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏοÏÏηÏιζÏμενα ÏημειÏÎ½Î¿Ï Î¼Îµ Ïα ακÏÎ»Î¿Ï Î¸Î± ..Î Î§Î¿Ï ÏιανÏÏ Î¼ÏÎ¸Î¿Ï Î¼Îµ ÏίÏλο Ïο "ΤÏαγοÏδι ÏÎ¿Ï Ullikummi" (ÏεÏ. 1200 Ï.Χ.) εÏιβιÏνει ÏÏην ΧεÏÏιÏική εκδοÏή ÏÎ¿Ï , εξ ανÏιγÏαÏÎ®Ï - ÏÏοÏαÏÎ¼Î¿Î³Î®Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïο Î§Î¿Ï ÏÎ¹Î±Î½Ï Ï ÏÏδειγμα, Ïε ÏÏÎµÎ¯Ï ÎºÎ±ÏακεÏμαÏιÏμÎÎ½ÎµÏ ÏÎ®Î»Î¹Î½ÎµÏ ÏÎ¹Î½Î±ÎºÎ¯Î´ÎµÏ ÏÎÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎµÏ ÎºÎµÎ¯Î¼ÎµÎ½Î¿ Ïε ÏÏηνοειδή,[22] αÏοÏελοÏμενο αÏÏ 300 γÏαμμÎÏ ÏεÏίÏÎ¿Ï .[23] ÎÏονÏÎ±Ï Î»Î¬Î²ÎµÎ¹ Ïο Ïνομά ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïο ομÏÎ½Ï Î¼Î¿ ÏÏ ÏÎ»Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ κÏÏÏ Î»Î¯Î¸Î¹Î½Î¿ ÏÎÏαÏ, η ιÏÏοÏία ÏεÏιγÏάÏει ÏÎ¹Ï Î¼Î·ÏανοÏÏαÏÎ¯ÎµÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Kumarbi, ενÏÏ Î¼Î½Î·ÏÎ¯ÎºÎ±ÎºÎ¿Ï ÎµÎºÎ¸ÏονιÏμÎÎ½Î¿Ï Î¸ÎµÎ¿Ï, ο οÏÎ¿Î¯Î¿Ï ÎµÏÎ¹Î¸Ï Î¼ÎµÎ¯ να ÏÏεÏεÏιÏÏεί Ïον θÏÏνο αÏÏ Ïον Ï Î¹Ï ÏÎ¿Ï , Î¸ÎµÏ ÏÎ·Ï Î¸ÏÎµÎ»Î»Î±Ï Tesub. Îια Ïην εÏιÏÏ Ïία ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ³ÏειÏήμαÏÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿ Kumarbi ÏÏ Î½ÎµÏ ÏίÏκεÏαι εÏÏÏικά με βÏάÏο και ÎÏÏι ÏÏοκÏÏÏει εκ ÏÎ¿Ï Î»Î¯Î¸Î¿Ï Î³ÎνεÏη ÏνÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏκεÏά ιÏÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÏε να καÏαÏÏÏÎÏει ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î¸ÎµÎ¿ÏÏ, ο μÏÎ¸Î¿Ï Î´Îµ ÏαÏαβάλλεÏαι ÏÏÎ¿Ï Î±Ï ÏÏν ÏÎ¿Ï Î¤Ï ÏÏνοÏ. Î£Ï Î¼ÏεÏαÏμαÏικά και εν ÏÏ Î½ÏÏει ÏÎÏÎ±Ï Ïο οÏοίο αÏοÏÏÎλλεÏαι αÏÏ ÏÎ¹Ï ÎºÎ±Î¸Î±Î¹ÏεθείÏÎµÏ ÏαλαιÎÏ Î´Ï Î½Î¬Î¼ÎµÎ¹Ï ÏÏν θεÏν αÏειλεί Ïον νÎο Î¸ÎµÏ ÏÏο ÎάÏιον ÏÏÎ¿Ï (Î£Ï Ïία), καÏά δε Ïον Guterbock[24] οι διαÏοÏÎÏ Î¼ÎµÏÎ±Î¾Ï ÏÏν διαÏÏÏÏν εκδοÏÏν (ÎÎ±Î²Ï Î»ÏνιακÏν, Î§Î¿Ï ÏιανÏν, ÎλληνικοÏ) ÎγκεινÏαι ÏÏÎ¹Ï Î»ÎµÏÏομÎÏÎµÎ¹ÎµÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÏο ÏÏÎ¿Ï - ÏνεÏμα. ÎιακÏÏÏονÏÎ±Ï Î®, μάλλον, ÏεÏμαÏίζονÏÎ±Ï Ïην αÏήγηÏή Î¼Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏ Î³ÎºÎµÎºÏιμÎÎ½Î¿Ï Î¼ÏÎ¸Î¿Ï ÏημειÏÎ½Î¿Ï Î¼Îµ ÎµÎ´Ï ÏÏι η Îννοια ÏÎ·Ï Î³Î®Ï Î¼Î·ÏÏÏÏ (terra mater) εκÏιμάÏαι ÏÏι είÏε διαμοÏÏÏθεί ήδη αÏÏ Ïην νεολιθική ÏεÏίοδο, και μάλιÏÏα ενείÏε ÏαÏακÏηÏιÏÏικά ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÏιÏÏÏÏθεÏα ÏÏ Î½Îδεαν Ïην γή και με Ïο Ï Î´Î¬Ïινο ÏÏοιÏείο,[25] ÏÏÏÏ ÏαίνεÏαι να ÏÏ Î¼Î²Î±Î¯Î½ÎµÎ¹ καÏά Ïο ÏÏÏÏο ÏκÎÎ»Î¿Ï ÏÏον μÏθο ÏÎ¿Ï Ullikummi ÎµÎ½Ï ÎºÎ±Ïά Ïο δεÏÏεÏο μοιάζει να εκÏÏάζεÏαι, μεÏÎ±Î¾Ï ÏÏν άλλÏν, ÏÏον άλλο Î§Î¿Ï ÏÎ¹Î±Î½Ï Î¼Ïθο, Ïο "ΤÏαγοÏδι ÏÎ¿Ï Hedammu". Το ÏÎµÎ»ÎµÏ Ïαίο, ÏÏζÏμενο εÏίÏÎ·Ï ÏÏην ΧεÏÏιÏική εκδοÏή ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïην ÏεÏίοδο ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎÎ¿Ï Î§ÎµÏÏιÏÎ¹ÎºÎ¿Ï Î²Î±ÏÎ¹Î»ÎµÎ¯Î¿Ï [26] Ïε μιά ανάλογη εξιÏÏÏÏηÏή ÏÎ¿Ï ÏάÏεÏν ÏÎ·Ï Î³ÎµÎ½ÎµÎ±Î»Î¿Î³Î¯Î±Ï ÏÏν θεÏν ÏεÏιλαμβάνει Ïην γÎνεÏη ιÏÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎÏαÏÎ¿Ï Î±Ï Ïήν Ïην ÏοÏά αÏÏ Ïην θάλαÏÏα ..

ΣÏα ÏλαίÏια Î¼Î¹Î¬Ï Î¹Î´Î¹ÏμοÏÏÎ·Ï ÏάÏεÏÏ Î³Î¹Î± ÏÎµÏ Î´Î¿ - εÏιÏÏημονική οÏθÏÏηÏα, Î±Ï Î±ÏοκαλÎÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Îµ ÎÏÏι με Ïην ÏειÏά Î¼Î±Ï Ïον ÏÏο scientifically correct, είμαÏÏε μάÏÏÏ ÏÎµÏ ÏÏοÏÏαθειÏν εÏÎµÏ Î½Î·ÏÏν οι οÏοίοι ÏÏ Î½Î±Î³ÏνίζονÏαι ÏÏοκειμÎÎ½Î¿Ï Î½Î± ενÏοÏίÏÎ¿Ï Î½ και αναγνÏÏίÏÎ¿Ï Î½ νÎα ÏεκμήÏια για Ïην εξάÏÏηÏη ÏÏν ÎμηÏικÏν εÏÏν αλλά και ÏÎ¿Ï Î¼ÎÏÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏÏ ÎναÏολικά αÏÏÎÏÏ Ïα,[27] ex oriente lux. ÎÏÏι ÏÏο αÏÏÏÏαÏμα ÏÎ·Ï ÎÎ»Î¹Î¬Î´Î¿Ï 16.33-35 ανακαλÏÏÏονÏαι νÎÎµÏ ÎµÏιÏÏοÎÏ Î±ÏÏ Ïην ÎγγÏÏ ÎναÏολή. Î£Ï Î³ÎºÎµÎºÏιμÎνα η ÎλεÏÎ¯Î´Î¿Ï ÏημειÏνει:[28]ÎÏ ÏÏ Ïο άÏθÏο εÏανεξεÏάζει Ïο ÏεÏίÏημο ÏÏÏλιο ÏÎ¿Ï Î Î±ÏÏÏÎºÎ»Î¿Ï Î³Î¹Î± Ïην ÏκληÏÏÏηÏα ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏιλλÎα, ÏÏο οÏοίο η θάλαÏÏα και οι βÏάÏοι Î±Î½Î±Î»Î±Î¼Î²Î¬Î½Î¿Ï Î½ Ïον ÏÏλο ÏÏν γονÎÏν ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎµÎ»ÎµÏ ÏÎ±Î¯Î¿Ï (Îλ. 16.33â35). Îι ÏÏίÏοι ανÏικαÏοÏÏÏÎ¯Î¶Î¿Ï Î½ μÏÎ¸Î¿Ï Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎγγÏÏ ÎναÏÎ¿Î»Î®Ï ÏÏεÏικά με Ïη γÎννηÏη αÏειληÏικÏν ÏλαÏμάÏÏν αÏÏ Ïην θάλαÏÏα και ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î²ÏάÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÏ Î½Î´ÎονÏαι ιδιαίÏεÏα με Ïο ΤÏαγοÏδι ÏÎ¿Ï Hedammu και Î±Ï ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ullikummi ÏÎ·Ï Î§Î¿ÏÏο-ΧεÏÏιÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÏαÏαδÏÏεÏÏ. ÎεμαÏικοί, Î¼Ï Î¸Î¿Î»Î¿Î³Î¹ÎºÎ¿Î¯ και ÏÏαÏεολογικοί ÏαÏαλληλιÏμοί μεÏÎ±Î¾Ï Î±Ï ÏÏν ÏÏν κειμÎνÏν ÏÏ Î¶Î·ÏοÏνÏαι ÏÏοκειμÎÎ½Î¿Ï Î½Î± διεÏÎµÏ Î½Î·Î¸ÎµÎ¯ η ÏÏαÏξη ενÏÏ ÎºÎ¿Î¹Î½Î¿Ï Î¸ÎμαÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Îµ ÏÏ Î³ÎºÎµÎºÏιμÎÎ½ÎµÏ ÏÏ Î½Î´Î·Î»ÏÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÏÏην ÎµÏ ÏÏÏεÏη ÏεÏιοÏή ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏ ÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎÏίαÏ.Î ÏÏκειÏαι ÏÏ Î³ÎºÎµÎºÏιμÎνα για Ïο Ïημείο ÏÏÎ¿Ï Î¿ ΠάÏÏÎ¿ÎºÎ»Î¿Ï ÏÏÏεÏÏÎ¼ÎµÎ½Î¿Ï ÎµÎ½Î±Î½Ïίον ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏιλλÎÏÏ Î³Î¹Î± Ïην αÏÏαξία ÏÎ¿Ï , ÏαÏά ÏÎ¹Ï Î´Ï ÏÎ¼ÎµÎ½ÎµÎ¯Ï Î³Î¹Î± ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÎÏαιοÏÏ ÎµÎ¾ÎµÎ»Î¯Î¾ÎµÎ¹Ï, ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Ïαλογίζει: οá½Îº á¼Ïα Ïοί γε ÏαÏá½´Ï á¼¦Î½ á¼±ÏÏÏÏα ΠηλεÏÏ,/ οá½Î´á½² ÎÎÏÎ¹Ï Î¼Î®ÏηÏËÎ³Î»Î±Ï Îºá½´ δΠÏε ÏίκÏε θάλαÏÏα /ÏÎÏÏαι Ïá¾½ ἠλίβαÏοιΠÏÏοÏÏÏινή, ÏÏÏÏ Î³Î½ÏÏÎ¯Î¶Î¿Ï Î¼Îµ, αÏÏαξία ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏιλλÎÏÏ, αÏαÏαίÏηÏη ÏμÏÏ Î³Î¹Î± Ïην κοÏÏÏÏÏη ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ½Î´Î¹Î±ÏÎÏονÏÎ¿Ï Î±Î»Î»Î¬ και Ïην ÏαÏÎ¿Ï ÏίαÏη αμÏοÏÎÏÏν ÏÏν ÎιοÏκοÏÏειÏν ÏÎ»ÎµÏ ÏÏν ÏÎ¿Ï Î®ÏÏοÏ, αÏοδίδεÏαι λοιÏÏν ÏÏο ÏÏÏίο ÏÏην γÎννηÏή ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏι αÏÏ Ïον ΠηλÎα και Ïην ÎÎÏιδα αλλά αÏÏ Ïην θάλαÏÏα και ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î»Î¯Î¸Î¿Ï Ï (ÏÏήλαια, βÏάÏÎ¿Ï Ï). Î ÏÏάÏη ÎÏει εÏÎ¼Î·Î½ÎµÏ Ïεί αÏÏ Ïον Janko ÏÏ Î¿ÏειλÏμενη Ïε μιά γενική ανÏίληÏη αÏÎ¿Î´Î¯Î´Î¿Ï Ïα Ïην γÎννηÏη ÏÎ·Ï Î±Î½Î¸ÏÏÏÏÏηÏÎ±Ï Ïε ÏÏÏÏαÏÏικά ÏÏοιÏεία, ÏμÏÏ Î· εÏιÏÏημονική οÏθÏÏÎ·Ï Î´Ï ÏκολεÏεÏαι να αÏοδεÏθεί Ïην άÏοÏη .. ÎÏÏ Ïην άλλη ÏειÏά ÏαλαιÏν αλλά και ÏÏγÏÏονÏν ÏÏολιαÏÏÏν ÏÎ¿Ï ÎμήÏÎ¿Ï Î¸ÎµÏÏοÏν ÏÏι η θάλαÏÏα και οι βÏάÏοι αÏοÏελοÏν μεÏÏÎ½Ï Î¼Î¯Î± ÏÎ·Ï ÎÎÏÎ¹Î´Î¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÎ¿Ï Î Î·Î»ÎÏÏ, αλλά και Î±Ï Ïή η θεÏÏηÏη αÏοÏÏίÏÏεÏαι εÏίÏÎ·Ï ÏÏ Î¼Î· ÏÏ Î¼Î²Î¹Î²Î±Î¶Ïμενη με Ïην ÏÏοκÏοÏÏÏεια κλίνη ÏÎ¿Ï ÎναÏολιÏÎ¼Î¿Ï .. εÏίÏηÏ...

Îξίζει να ÏÏοÏÏεθεί ÎµÎ´Ï ÏÏι η ÎλεÏÎ¯Î´Î¿Ï ÎµÏιÏειÏεί να ενÏάξει Ïον ÎÏιλλÎα ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î±Î½ÏαγÏνιÏμοÏÏ ÏÏν θεÏν, ÏημειÏνονÏÎ±Ï ÏÏι ο ΠίνδαÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏα ÎÏθμια, Isth. 8.27â45, Ïον ÏαÏακÏηÏίζει ÏÏ Î´Ï Î½Î·Ïική αÏειλή για Ïην θεÏκή ÎµÎ¾Î¿Ï Ïία ÏÎ¿Ï ÎιÏÏ![29]

ÎαÏαληκÏικÎÏ ÏαÏαÏηÏήÏειÏΧÏÏÎ¯Ï Î½Î± αÏοÏÏίÏÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Îµ ÏÎ¹Ï ÎµÏαÏÎÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ εÏιÏÏοÎÏ Î±ÏÏ Ïην ÎεÏοÏοÏαμία, θεÏÏοÏμε ÏÏι - μάλλον - Ïο ÎµÎ´Ï ÏÏολιαζÏμενο βιβλίο ÏÏÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ Ïο νεÏÏεÏο ÏÎ¿Ï 2022[30] Î±ÎºÎ¿Î»Î¿Ï Î¸ÎµÎ¯ Ïο ÏεÏμα ÎÎ ÎÎÎΤÎÎΩΠΤΠΦΩΣ ..ÎÏο μÏνον ÏαÏαÏηÏήÏειÏ: (α) ΠμÏÎ¸Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ´Ï ÏÏÎÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ Î Î¿Î»Ï ÏÎ®Î¼Î¿Ï ÎÏει Ï ÏοÏÏηÏιÏθεί ÏÏι διαθÎÏει ÏÏοιÏεία κληÏονομημÎνα αÏÏ Ïο αÏÏÏαÏο ÏαÏελθÏν, βλ. άνάÏÏηÏή Î¼Î¿Ï : ODYSSEUS & POLYPHEMOS ÏÏο ιÏÏολÏγιο: https://dnkonidaris.blogspot.com/ (β) Î ÏαÏακÏήÏÎ±Ï HUMBABA μÏοÏεί να θεÏÏηθεί ÏαÏÎ¬Î»Î»Î·Î»Î¿Ï Î±Ï ÏoÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÎÎΡÎÎΥΣ - ÎÎÎÎΥΣÎΣ για Ïην οÏοία Ï ÏοÏÏηÏίζεÏαι: ΠΡÎΪΣΤÎΡÎÎÎ ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎÎ Î ÎÎΤÎÎΩÎΠΤÎΣ ÎÎΡÎÎΥΣ - ÎÎÎÎΥΣÎΣ ; (prehistoric in time and wider Aegean origin of gorgonâmedousaâgorgonâs head - gorgoneion - repulsive image)

Î¥ÎÎÎÎ

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------https://www.degruyter.com/document/do... Oreshko. 2018. "Anatolian linguistic influences in Early Greek (1500â800 BC)? Critical observations against sociolinguistic and areal background," Journal of Language Relationship 16 (2), pp. 93â118... It would be fair to say that the existence of some cultural influence of Anatolia on Greek language and literature which may be dated as far back as the LBA is at present taken practically for granted. The assessments of the extent and depth of this influence, as well as of its exact source (the Hittites, the Luwians or some other peoples of Western or Southern Anatolia), may vary considerably from scholar to scholar, but the very idea seems to have assumed by now in the eyes of many (if not all) the quality of an established fact, mirroring in a way a similar process of ârecognitionâ of more general âOrientalâ influences in the early Greek literature. This belief is rooted in the obvious fact of immediate geographic proximity of Anatolia and the Aegean, in the somewhat less obvious but still demonstrable fact of contacts between the Mycenaean Greeks and Anatolian peoples and, lastly, in a far more problematic âand often subconscious â belief that Anatolia as a part of the Ancient Near East was culturally superior to the Aegean world in the Late Bronze Age, which should allegedly have automatically made the Greeks receptive to cultural impulses from this region. The underlying belief in the importance of the Anatolian factor for the Early Greek language and literature generated over the years an imposing (even if not all too dense) swarm of publications claiming to have found one or the other concrete instance of Anatolian or, to apply the term most frequently used for the most part of the 20th century, Hittite influence in the domain of Greek vocabulary, morphology or phraseology.2

p. 113: The results of this survey are certainly rather discouraging: considering the evidence soberly and without obsessive concentration exclusively on Anatolian and Greek, one should state that among the most frequently cited cases there is not a single one which may be properly qualified as contact-induced borrowing from an Anatolian language into Greek dating to the Late Bronze Age or Early Iron Age. p. 114: Similarly, the absence of bilingual communities makes it rather unlikely that the Greeks had any access to Anatolian literary texts (oral or written) and, consequently, an explanation for any eventual similarities in phraseology or literary themes between Greece and Anatolia â or, wider, the Ancient Near East â should be sought along different lines, such as generic or typological similarity, common heritage or common cultural experience.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ΠΠεÏÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Î»Î¿Ï ÏαÏαÏÎμÏει - και ÏαίνεÏαι ÏÏι ÏÏ Î¼ÏÏνεί - ÏÏον Griffin, Ï ÏοÏÏηÏικÏή ÏÎ·Ï ÎºÎ±Î¸ÏÎ´Î¿Ï ÏÏν 'ÏÏογÏνÏν ÏÏν ÎλλήνÏν' ÏÏον ÏÏÏο Ïο 1900 (άÏοÏη ήδη μη αÏοδεκÏή ..) [The Oxford History of Greece & the Hellenistic World, John Boardman, Jasper Griffin, Oswyn Murray, 1986, p. 4], διαÏοÏοÏοιεί ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÎακεδÏÎ½ÎµÏ Î±ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î¬Î»Î»Î¿Ï Ï ÎλληνεÏhttps://books.google.gr/books?redir_e..., J. 1986. "Greek myth and Hesiod," in The Oxford History of Greece & the Hellenistic World, ed. J. Boardman, J. Griffin, O. Murray, 1986, pp. 82-106.

Î ÎΤΡ.... Îια Ïην ελληνική Î¼Ï Î¸Î¿Î»Î¿Î³Î¯Î±, η οÏοία βαÏίζεÏαι ÏÏην εξελιγμÎνη μοÏÏή ÏÎ¿Ï Î¸ÏηÏÎºÎµÏ ÏÎ¹ÎºÎ¿Ï Î²Î¯Î¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï Î±ÏÏÎ±Î¯Î±Ï ÎλλάδαÏ,[4] [Griffin ..

ÎαÏακάνÏζα, ÎακÏβ Îανιήλ, Gordon, ÎμηÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÎÎ¯Î²Î»Î¿Ï !!http://digital.lib.auth.gr/record/159... Î ÎÎ ÎÎ¥ÎÎÎÎΣ!1-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------https://books.google.gr/books?id=Cnkf..., A. R. 2010. "The Epic of Gilgamesh," in The Cambridge Companion to the Epic, ed. C. Bates, Cambridge University Press, pp. 1-12.

Standard Babylonian epic of the first millennium

George 2010 <https://hozir.org/chapterid-978052188.... 4: The Sumerian poems report some of the same legends and themes as parts of the Babylonian poem, but they are independent compositions and do not form a literary whole. The Sumerian and Babylonian poems shared more than just a common literary inheritance, whether that was oral (asseems likely) or written...Altogether these eleven Old Babylonian manuscripts provide several disconnected episodes in a little over six hundred lines of poetry. S---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Yoram Cohen. 2016. Rev. of M. R. Bachvarova, From Hittite to Homer: The Anatolian Background of Ancient Greek Epic, in BMCR 2016.11.14, <https://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/2016/2016.1... (19 April 2021).-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------https://www.researchgate.net/publicat..., A. S. W. 2011. "Speech from Tree and Rock: Recovery of a Bronze Age Metaphor," American Journal of Philology 136 (1), pp. 1-35.Interpreters of archaic Greek epic poetry have long labored to explain the meaning of the semantically ambiguous phrase involving "tree (delta rho nu(sic)) and/or rock (pi epsilon tau rho eta)." The idiom appears three times in archaic epic: in the proem of Hesiod's Theogony, during Hector's deliberation about negotiating a truce in Iliad 22, and in Penelope's speech to a disguised Odysseus in Odyssey 19. A tantalizingly similar, and equally unsolved idiom, rgm w Ihst 'abn, appears in the thirteenth-century Ugaritic Ba'al Cycle found at Ras Shamra. Current scholarship agrees that this phrase connotes ideas of prophecy. This article argues that the phrase's history can be traced further back to a metaphor describing the audio-visual phenomenon of lightning and thunder as the storm-god's oracular speech. Crucial evidence for this account is found in Bronze Age material culture.---------------------https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/gil...

ΣÎÎÎÎΩΣÎÎΣ

[1]. Elmer 2017. ÎλλÏÏÏε Ïο 'ÏÏαγοÏδι ÏÎ¿Ï Ullikummi' αναγνÏÏίÏÏηκε αÏÏ Ïην αÏÏή ÏÏ ÏÏοκάÏοÏÎ¿Ï Î® Ï ÏÏδειγμα ÏÏν ελληνικÏν μÏθÏν ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏιÏÎ´Î¿Ï . ΠαÏαλληλιÏμοί με Ïον ÎµÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÏ Î¼Ïθο ÏÎ¿Ï Î¤Ï ÏÏνα, ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏÏÎ±Î¯Î¿Ï Î±Î½ÏαγÏνιÏÏή ÏÎ¿Ï Î¸ÎµÎ¿Ï ÏÏν κεÏÎ±Ï Î½Ïν Îία, ÎÏÎ¿Ï Î½ διαÏÏ ÏÏθεί αÏÏ Ïον Burkert[2]. dbpedia, s.v. Ullikummi (https://dbpedia.org/page/Ullikummi): Î ÏÏεÏική αναÏοÏά ÏÎ¿Ï Elmer (Ï.Ï.) ÎÏει ÏÏ ÎµÎ¾Î®Ï: In accounting for the origins of the Homeric Iliad, Bachvarova eventually concludes that the earliest Greek settlers in the region of the Troad found there an already established, native Anatolian tradition about the fall of Troy, which they subsequently adapted. This native tradition was itself shaped by Near Eastern traditions mediated by the Hittite Empire. Bachvarova develops a detailed stratigraphy of the Iliad, involving an early Luwian âWilusiad,â a later Phrygian tradition about the fall of Troy, various possible Greco-Anatolian bilingual traditions, and rivalry between Aeolic and Ionic singers in Anatolia (summary on 453â57). This is a complex model, open to question in some particulars, but the reality must surely have been at least as complex, if not more...[3]. van Dongen 2012, p. 25. ΠδιαÏÏθείÏα ΧεÏÏιÏική εκδοÏή ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏÎ³Î¿Ï ÏÏοÎÏÏεÏαι αÏÏ Ïην Ïινακίδα CTH 344, ÏÏονολογοÏμενη ÏÏα ÏÎλη ÏÎ¿Ï Î§ÎÎΠαι. Ï.Χ., ÏμÏÏ Î¸ÎµÏÏείÏαι ÏÏι ÏÏοÎÏÏεÏαι αÏÏ ÏαλαιÏÏεÏο Ï ÏÏδειγμα![4]. van Dongen 2010, p. 142. Το ÏÏÏÏÏÏÏ Ïο κείμενο ÎÏει ÏÏ ÎµÎ¾Î®Ï:In section 4.1.3, several narrative details were found to feature similarly in the variants of the âKingship in Heavenâ-theme of the Song of Going Forth and the Theogony: the roles of the kings in heaven (Anu/Ouranos, Kumarbi/Kronos, stormgod/Zeus), the castration of Anu/Ouranos when he is king of the gods, the presence of full-grown gods inside Kumarbi/Kronos, and the feeding to and spitting out of a stone by Kumarbi/Kronos, which subsequently becomes an object of veneration. [5]. ΧαÏακÏηÏιÏÏική ομοιÏÏηÏα είναι Î±Ï Ïή ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏεÏίζεÏαι με Ïην γÎνεÏη ÏÎ·Ï ÎθηνάÏ, η οÏοία ÏαÏαβάλλεÏαι με Î±Ï Ïήν ÏÎ¿Ï Î·ÏÏÏÎºÎ¿Ï Î²Î±ÏιλÎÏÏ KA.ZAL (Beckman & Arbor 2011, p. 25). [6]. Beckman & Arbor 2011, p. 25. [7]. Burkert 1995.[8]. Burkert 1992, p. 6.[9]. Burkert 1992, p. 16. Το ÏεκμήÏιο ÏÏ Î»Î¬ÏÏεÏαι ÏÏο ÎÎ¿Ï Ïείο ÎαÏλοβαÏÎ¯Î¿Ï , αÏ. B2579.[10]. ÎονιδάÏÎ·Ï 2022, Ïελ. 118, Ïημ. 8_98; Lawson 2016; Eph'al and Naveh 1989.[11]. Î ÏÏκειÏαι για Ïο αÏÏÏÏαÏμα Gilg. 3.39-45 αÏÏ Ïην Î¤Ï Ïική ÎκδοÏη (Standard Edition) ÏÎ¿Ï Gilgamesh, η οÏοία Îλαβε Ïην ÏÏÎÏÎ¿Ï Ïα, Ïελική μοÏÏή ÏÎ·Ï ÎºÎ±Ïά ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î±Î¹ÏÎ½ÎµÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÏÎµÎ»ÎµÏ ÏÎ±Î¯Î±Ï ÏιλιεÏÎ¯Î±Ï Ï.Χ. (Bakker 2001, pp. 331-332, n. 2; George 2010, p. 5), βλ. <https://uruk-warka.dk/Gilgamish/The%2.... Burkert 1992, pp. 99-100; Bakker 2001, pp. 331-332. Το ÏÏεÏÎ¹ÎºÏ Î±ÏÏÏÏαÏμα ÏÏο ÏÏÏÏÏÏÏ Ïο ÎÏει ÏÏ ÎµÎ¾Î®Ï: pp. 331-332The most obvious and rewarding Near Eastern parallel to Homer, though by no means the only one, is the Gilgamesh Epic that has been unearthed. in many places throughout the Near East. The most complete version of the epic is the so-called Standard Version, that has. been found in the form of eleven tablets in the library of King Ashurbanipal in Nineveh, Ancient Assyria, and that took final shape in the first centuries of the first millennium BCE.[2] Both West and Burkert assign to this Standard Version a key role in the relations between Homer and the Near East. Homeric epic, they argue, borrows from the neo-Assyrian standard version of Gilgamesh. West, in fact, goes as far as saying that there was some kind of «hotline» linking the Greek epic tradition with Assyrian court literature, of which the standard Gilgamesh was an important part. He imagines the existence of Greek poets traveling to Nineveh to become acquainted with Gilgamesh, Artahasis, and other Akkadian classics ; or alternatively, he thinks of a "disaffected" Assyrian [] poet "defecting" to the West, becoming Hellenized in the course of a few years, and turning into a Greek poet».[3: West 1997, 629, hotline: 627] It is hard to see how such a bilingual individual could shape the Homeric tradition so profoundly. This is not to reject, however, the very real possibility of a poetic component to the intensive contacts between the Greek world and Near East in the 8th and 7th centuries. Those contacts may have had a bearing on the Homeric poems in this crucial stage in their development, and it is entirely possible that the Gilgamesh Epic in its Standard Version lurks in the background of the Homeric imagination, and that certain scenes of the Near Eastern classic surface in the narrative of the Iliad and the Odyssey. Burkert in particular has pointed out striking similarities between certain Homeric scenes and Gilgamesh. The scene in which Penelope goes up the roof of the palace {Ï ÏεÏÏα - ανÏγι] and prays to Athena after she has learned of Telemachos's departure[4: Od. 4. 759-767] bears a close resemblance, he points out, to Gilg. 3.39-45 where Ninsun, Gilgamesh's mother, does the same, praying to Shamash the sun god, after Gilgamesh's and Enkidu's departure on their risky journey to Humbaba, the Guardian of the Cedars.[5: Burker 1992, 99-100][13]. Burkert 1992, p. 61. ΠεÏί Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏολιάÏαμε ÏÏην Î' ÏαÏαÏήÏηÏη ÏÎ¿Ï Î' μÎÏÎ¿Ï Ï.[14]. Burkert 1992, p. 109.[15]. Burkert 1992, 109.[16]. Nagy 2020; ÎονιδάÏÎ·Ï 2022, Ïελ. 205, Ïημ. 10_21.[17]. ÎονιδάÏÎ·Ï 2022, Ïημ. 10_27.[18]. Chantraine 1968, p. 261.[19]. Bachvarova 2018, pp. 8-9.[20]. βλ. ανÏÏÎÏÏ Îº. Χ.[21]. Bachvarova 2018, p. 8.[22]. McClanahan 2021. [23]. Guterbock 1951, p. 136.[24]. Guterbock 1951, p. 145.[25]. York 1993, p. 248. [26]. Bachvarova 2018, p. 9.[27]. Îachvarova 2016, pp. 458â464.[28]. Alepidou 2019.[29]. Alepidou 2019, p. 17, n. 49.[30]. Petropoulos 2022.

ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎΡÎΦÎÎ

https://www.academia.edu/4998534/The_..., E. 2001. "The Greek Gilgamesh, or the Immortality of Return," in ÎΡÎÎÎΣ. ÎÏá½¹ Ïα ÏÏακÏικά ÏÎ¿Ï Îá¾½ Î£Ï Î½ÎµÎ´Ïá½·Î¿Ï Î³Î¹Î± Ïην ÎδύÏÏεια (2-7 ΣεÏÏεμβÏá½·Î¿Ï 2000), Îθάκη: ÎένÏÏο ÎÎ´Ï ÏÏειακών ΣÏÎ¿Ï Î´á½½Î½, pp. 331-353.

https://dataspace.princeton.edu/handl..., T. H. 2021. "Greek Cosmology and Its Bronze Age Background" (diss. Princeton University).

López-Ruiz, C. 2016. "Cosmogonies and theogonies," Oxford Classical Dictionairy, <https://oxfordre.com/classics/view/10... (10 Oct. 2022).

https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780... online: 07 March 2016

West, M. L. 1997. The East Face of Helicon: West Asiatic Elements in Greek Poetry and Myth, Clarendon Paperbacks.https://www.jstor.org/stable/631836

https://books.google.gr/books?id=fIp0... Antiquity 5Burkert, W. 1992. The Orientalizing Revolution. Near Eastern Influence on Greek Culture in the Early Archaic Age, Cambridgehttps://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/2000/2000.0...

https://books.google.gr/books/about/T..., W. 1992. The Orientalizing Revolution: Near Eastern Influence on Greek Culture in the Early Archaic Age, Harvard University Press.

Lawson (Younger, Jr.), K. 2016. "Why the Arameans?," ANE Today IV (12), <https://www.asor.org/anetoday/2016/12... (9 Oct. 2022).

https://www.jstor.org/stable/i2792614..., L. and J. Naveh. 1989. "Hazael's Booty Inscriptions," Israel Exploration Journal 39 (3/4), pp. 192-200.

ÎονιδάÏηÏ, Î. Î. 2022. Îι ΧεÏÏαίοι και ο κÏÏÎ¼Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ¹Î³Î±Î¯Î¿Ï , Îθήναι.

https://brill.com/view/journals/yago/..., A. 2019. âNear-Eastern Echoes in Iliad XVI 33-35.â CHS Research Bulletin 7.

https://research-bulletin.chs.harvard..., A. 2019. "Near Eastern Echoes in Iliad 16.33â35," in Yearbook of Ancient Greek Epic Online 4 (1), pp. 1-26.

https://muse.jhu.edu/article/667429Elmer, D. F. 2017. Rev. of M. R. Bachvarova, From Hittite to Homer: The Anatolian Background of Ancient Greek Epic, in Classical World 110 (4), pp. 590-592.

https://www.degruyter.com/document/do... Oreshko. 2018. "Anatolian linguistic influences in Early Greek (1500â800 BC)? Critical observations against sociolinguistic and areal background," Journal of Language Relationship 16 (2), pp. 93â118.

http://limudbchevruta.wiki.huji.ac.il..., H. G. 1951. "The Song of Ullikummi Revised Text of the Hittite Version of a Hurrian Myth," Journal of Cuneiform Studies 5 (4), pp. 135-161.

https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint... Dongen, E. W. M. 2010. "Studying external stimuli to the development of the ancient Aegean. The âKingship in Heavenâ-theme from Kumarbi to Kronos via Anatolia" (diss. Univ. College London).

Kumarbi: Mythen vom churritischen Kronos

https://www.jstor.org/stable/1579554?..., H. G. 1951. Rev. of H. Otten, Mythen vom Gotte Kumarbi. Neue Fragmente, in Oriens 4 (1), pp. 137-139.

https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstr..., G., A. Arbor. 2011. "Primordial Obstetrics. 'The Song of Emergence' (CTH 344)," Alter Orient und Altes Testament 391, pp. 25-33.

https://books.google.gr/books?id=wxd-..., M. R. 2016. From Hittite to Homer: The Anatolian Background of Ancient Greek Epic, Cambridge.https://www.academia.edu/39143309/Fro...

McClanahan, J. R. 2021. "Stone Births in Western Mythology," <https://journeytothewestresearch.com/... (25 April 2021).

http://limudbchevruta.wiki.huji.ac.il..., H. G. 1951. "The Song of Ullikummi Revised Text of the Hittite Version of a Hurrian Myth," Journal of Cuneiform Studies 5 (4), pp. 135-161.

https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/27910..., A. R. 2010. The Epic of Gilgamesh, Cambridge Univ. Press, pp. 1-12.

https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/1603/1/Geo..., A. R. 2001. The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic I, Oxford Univ. Press.interesting see p. 3-4-5!

https://www.academia.edu/39143038/Mul..., Î. Ρ. 2018. "Multiformity in the Song of Ḫedammu," Altorientalische Forschungen 45(1), pp. 1â21.

Yoram Cohen, 2016. Rev. of M. R. Bachvarova, From Hittite to Homer: The Anatolian Background of Ancient Greek Epic, in BMCR 2016.11.14, <https://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/2016/2016.1... (25 April 2021).

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/1..., M. 1993. "Toward a Proto-Indo-European vocabulary of the sacred," Word 44:2, pp. 235-254.

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journa..., C. 2016. Rev. of M. R. Bachvarova, From Hittite to Homer: The Anatolian Background of Ancient Greek Epic, in The Classical Review 67(1), pp. 3-5.

https://willamette.edu/arts-sciences/...

Baughan, E. P. 2011. "Sculpted Symposiasts of Ionia," American Journal of Archaeology 115 (1), pp. 19-53.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/23342111van Dongen, E. 2012. "The Hittite "Song of Going Forth" (CTH âââ): A Reconsideration of the Narrative," Die Welt des Orients 42 (1), pp. 23-84.

GILGAMESHhttps://history.stackexchange.com/que...

http://www.ancienttexts.org/library/m...

https://www.academia.edu/66394331/Hum...

Petropoulos, E. K. 2022. "Human-Divine Interactions in Homer, Hittite and Other Near Eastern Literary Traditions," in Conceptualising Divine Unions in the Greek and Near Eastern Worlds (Ancient Philosophy & Religion, Vol. 7), ed. E. Pachoumi, Leyden / Boston, pp. 119-147.â https://www.jstor.org/stable/25066876..., F. K. 1986. Rev. of W. Martini, Das Gymnasium von Samos, in AJA 90, pp. 496â499.

Jean Collins, B. Rev. of H. G. Güterbock, K. Aslihan Yener, H. A. Hoffner, Jr. Recent Developments in Hittite Archaeology and History: Papers in Memory of Hans G. Güterbock, in BASOR 337, pp. 95-97.

Watkins C. 1998. âHomer and Hittite Revisited,â in Style and Tradition: Studies in Honor of Wendell Clausen, ed. P. Knox, C. Foss, pp. 201â211.

https://biblio.ugent.be/publication/8...

Nadine Nys. 2018. âThe Sphinx unriddledâ (diss. Ghent Univ.).

https://api.follow.it/trackstatistics... Fries. 2021. "The Mountain in Labour: A Possible Graeco-Anatolian Myth," Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 61 (4), pp. 423-445.The Graeco-Latin proverb and fable of the âmountain that gives birth to a mouseâ, with Athenaeusâ version in which Zeus expresses fear at the impending birth, can be connected with the motif of the âmountain in labourâ of the Hurro-Hittite Kumarbi Cycle.

https://books.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/pr..., D. 2019. Monsters and the Mind. Composite Creatures and Social Cognition in Aegean Bronze Age Glyptic (Daidalos â Heidelberger Abschlussarbeiten zur Klassischen Archäologie), Propylaeum.Humbaba, Medusa etc

https://www.academia.edu/keypass/eEV0..., M. 2018. "The Origin of the Different: 'Gorgos' and 'Minotaurs' of the Aegean Bronze Age," in Making Monsters, ed. E. Bridges and D. al-Ayad, pp. 165-175.

https://www.zora.uzh.ch/id/eprint/138..., H. U., ed. 2020. Gilgamesh: Epic and Iconography (Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 245), Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

p. 104 .. The dogs and the archer have not yet appeared in any literary version of the slaying of Huwawa, so again it may be that the Mesopotamian artistic tradition was used in this case for a local myth or legend. Clark Hopkins in 1934[34: https://www.jstor.org/stable/498901] demonstrated that this scene of Mesopotamian origin was the source of Aegean depictions of Perseus slaying the Gorgon: the original Huwawa (himself an improvisation) in some form reached the Aegean and was there t

Published on October 12, 2022 01:49

No comments have been added yet.