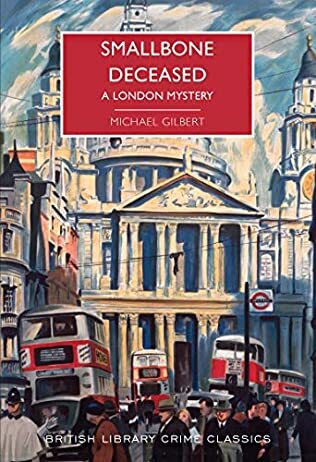

Smallbone Deceased

A review of Smallbone Deceased by Michael Gilbert

Originally published in 1950 and now reissued as part of the excellent British Library Crime Classics series, Smallbone Deceased is the fourth in Michael Gilbert’s Inspector Hazelrigg and is a must-read for all fans of Golden Age detective fiction. It has many of the elements that make up a good yarn, a seemingly impossible murder, misdirections and red herrings galore, and an amateur sleuth in the form of newly arrived solicitor, Henry Bohun, all underpinned by Gilbert’s inside knowledge of life in a London solicitor’s office. Above all, it is great fun.

Having been a partner in a legal firm himself, Gilbert paints his setting convincingly, alive to the tedium of office life, with its set routines, its petty jealousies, underlying and barely disguised tensions and rivalries. His characters are wryly and sharply observed and although stereotypical, are believable. The reader gets to know them, understands how they interact and becomes aware of the politics of a firm that on the surface is outwardly respectable and prosperous but in reality is struggling.

It has been rocked by the death of the senior partner, Mr Horniman senior, who has finally succumbed to his weak heart, and the prickly Mr Birley and the more approachable Mr Birley along with the newly promoted son of Mr Horniman are left to navigate the firm through choppy waters. One of Horniman’s lasting legacies is an orderly administrative system with a place for every paper and deed and every paper and deed in its place. Into this order, Gilbert mischievously adds a twist of the macabre.

Inside one of the firm’s seventeen deed boxes is found a body. It is not just any old body but that of Marcus Smallbone, the other trustee of a trust that Horniman senior was administering. Smallbone, whom we never meet alive, was seemingly an unpleasant individual and liked little more than digging up the dirt on others, not for pecuniary gain but for the satisfaction of getting one over his victims. The suggestion is that he has found out that Horniman has perpetrated a fraud to keep his firm afloat. As Horniman senior could not have murdered Smallbone, who did it?

Inspector Hazelrigg leads the investigation from the police perspective and enlists the assistance of Bohun who conducts enquiries from the inside. Unlike many writers who use the combination of professional police and amateur sleuth to highlight the stupidity of the former and the brilliance of the latter, Gilbert shows them working well together as they set about cracking a difficult case. Through dogged persistence the duo work out that there was only a particular window of opportunity for the murderer to strangle the victim, forensic evidence suggests that the culprit was left-handed, secrete the body in the deed box and remove the papers from an office where any paper out of order was instantly spotted.

It turns into one of those stories where alibis are tested and charts are developed showing the precise movements of suspects. However, Gilbert writes with considerable verve and handles the alibi testing with a commendable light touch. The suspects are whittled down until it can only be one and to many a reader their identity may come as a surprise. The one weakness of the book is motivation. Loyalty can exercise a powerful hold on an individual but is it enough to lead someone to commit a murder, never mind buy a new rucksack?

Despite this reservation it is a wonderful book and is thoroughly recommended.