“Overhead Triceps Extensions are (NOT) Better Than Neutral Arms Triceps Extensions”

of Scientific Studies (a series)Part 1

A study was recently done which attempted to compare the resultant muscle growth of two different triceps exercises. The study was reported in “PubMed.gov”:

The two exercises that were compared were the “Overhead Cable Triceps Extension”…and the standard “Cable Triceps Pushdown”.

The participants did one of those exercises with their left arm, and the other triceps exercise with their right—for a 12 week period of time. Then the triceps growth of each arm was measured. The conclusion of the researchers was: “The overhead triceps exercise produced more triceps growth than the neutral arm (arms down alongside the torso) triceps exercise.”

Suddenly, that “conclusion” was being reported in a wide variety of fitness journals, touted by numerous so-called “evidence-based” personal trainers, and even announced by professors of Exercise Physiology, including Brad Schoenfeld, Ph.D.

Here’s an example of a fitness journal “report” on that study, and its conclusion.

However, there is a serious flaw in this conclusion, and it stems from the assumption that the only difference between the two exercises being compared was the position of the arm, relative to the shoulder joint. That was NOT the only difference. In fact, it was not even the primary difference, although it would appear that way to most people.

Keep in mind that “Exercise Physiology” explores the science of what happens INSIDE a muscle when it contracts. It often fails to explore what’s happening OUTSIDE the body—the physics (mechanics) of the exercise.

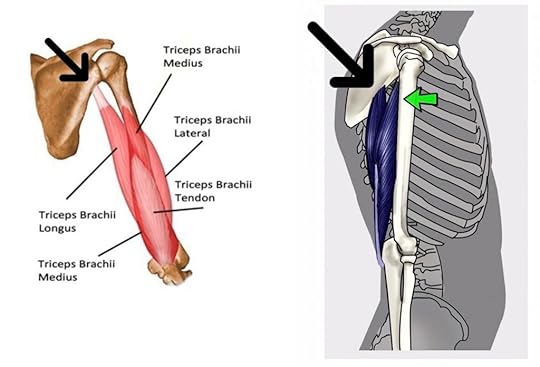

Most students of anatomy know that the triceps is a muscle comprised of three parts (known as “heads”). These are known as the the “long head” (“Longus”), the “lateral head” and the “medial head” (Medius).

In the images below, you can see these three parts, and you can see that the “long head” originates on the scapula (i.e., the outer edge of the shoulder blade), indicated by the black arrows. The other two parts—the “lateral head” and the “medial head”—originate directly on the upper arm bone (the humerus), indicated by the green arrow. Then, all three parts converge on the one single tendon, which crosses the elbow and attaches to the ulna of the forearm. When the triceps contracts, it extends the elbow.

Notice above that the origin of the Long Head on the scapula is below the shoulder joint. What this means is that when the arm is positioned overhead, the Long Head has the potential to stretch more. The other two parts of the triceps do not change their length, when the arms are positioned overhead. The lateral and medial heads don’t even “know” the position of the shoulder (i.e., the humerus). They function the same either way—whether the arms up or down.

Most students of exercise science also know that—during a resistance exercise—the “early” part of the range of motion is more important (in terms of muscle development) than the latter part of the range of motion.

Moreover, they know that “stretching” a muscle (maximum elongation during a resistance exercise) further adds benefit to a resistance exercise. This is why it’s reasonable to assume that an overhead triceps exercise COULD be more beneficial for the Long Head of the triceps. It is not automatically more beneficial, because it depends on how much the elbow is bent, WHILE the arms are overhead.

In other words, if you do not fully bend your elbows when doing an overhead triceps exercise, the Long Head of the triceps may not stretch any more than it would if your arms are down alongside your torso, but you bent your elbows farther. And it should be noted, that MOST people who perform overhead triceps exercises do NOT fully bend their elbows. Which means they are not taking advantage of the extra stretch potential of the Long Head, while in that arms-overhead position.

One of the outcomes that the researchers noted in their study was that “all three parts of the triceps improved more with the overhead version, as compared with the neutral arm (arms down) version.”

This outcome mystified the researchers, and they struggled to explain it. One hypothesis that the researchers considered was that it might be due the blood flow moving in the opposite direction (in the arm) when the arms are overhead, as compared with the neutral arm version. In fact, they were “grasping at straws”.

Again, remember that the Lateral Head and the Medial Head of the triceps do not change their function when the position of the arm (humerus / shoulder joint) changes. They don’t even KNOW whether the arms or up or down. Therefore, there is no logical reason why they would benefit more from an overhead triceps exercise, as compared with an “arms down” triceps exercise.

Yet, apparently none of the researchers thought, “hmmm…maybe the fact that all 3 heads of the triceps improved more with the overhead version indicates that some OTHER reason caused the better outcome….maybe it was NOT due to the arms up / shoulder position.”

In fact, the researchers mistakenly assumed (as did all those who later embraced the conclusion of the study), that the only difference between the two exercises was the position of the arms / shoulders. This demonstrates a gross lack of awareness of exercise mechanics. They were focused entirely on what’s happening INSIDE the body (the shoulder position), and completely missed what’s happening OUTSIDE the body — the physics of the exercise, as it interacts with the body.

As I mentioned earlier, most students and professors of “exercise physiology” know that “early phase loading” is better (more productive) than “late phase loading”.

The reason for this is that a muscle is stronger during the early part of its range of motion—when it is more elongated. A muscle is generally weaker during the latter part of its range of motion—when it is more shortened.

Below, you can see how this is explained by professors William Kraemer, Ph.D. and Steven Fleck, Ph.D.

The above is referencing the “strength curve” of most muscles.

Since muscles are generally stronger during the early part of their range of motion and weaker during the latter part of their range of motion, the wisest strategy for optimizing muscle development is to select exercises that provide a “resistance curve” that MATCHES the strength curve of the target muscle.

This allows the muscle to be maximally challenged when it is strongest (during the early phase), yet not overwhelmed with too much resistance later when it is weakest (during the late phase).

However, “strategic exercise selection” requires an understanding of lever mechanics (i.e., a component of physics). When this knowledge is applied to the human body, it is known as “biomechanics”. This is the type of awareness that is needed in order to understand “what is happening OUTSIDE the body.” This was completely overlooked by the researchers, and this is why their conclusion is wrong.

The researchers thought they were ONLY comparing the difference of the arm position between the two different triceps exercises. However, the two exercises they compared have a drastically different resistance curve, which produce a drastically different degree of benefit.

In my book (“The Physics of Resistance Exercise”), on pages 300 through 304, I explain why the standard Cable Triceps Pushdown (i.e., the “neutral arm” exercise used in this study) has a compromised resistance curve.

In order to “early phase load” a muscle, the exercise you select MUST provide a direction of resistance that is mostly perpendicular to the limb that is being operated by your target muscle, during that early part of that range of motion. When working the triceps, this means that the direction of resistance (in this case, the cable) must be mostly perpendicular to the forearm, when the elbow is most bent (flexed). Yet, that is NOT what happens during standard Cable Triceps Pushdown.

In the image above-left, I’ve highlighted the direction of the resistance (the cable) in GREEN, and you can see that it is NOT perpendicular to the forearm when the elbow is most bent (the early phase of the triceps’ range of motion). It’s closer to parallel, which means it’s loading the triceps with a very small percentage of resistance, precisely when the triceps is strongest. This is NOT good.

In the image above-right, I’ve highlighted an alternate direction of resistance (in GREEN)—one that would provide a very perpendicular direction of resistance during the critically important “early phase.”

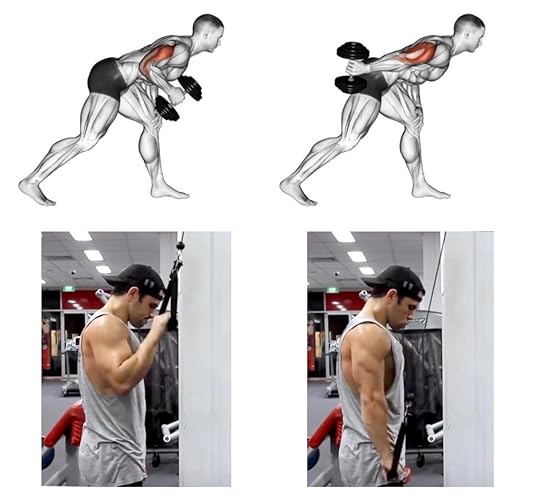

How would you do this? You either change the direction of the resistance, or you change the position of your body relative to the resistance. Below are two examples of this.

The “overhead” triceps exercise that the researchers used for their comparison provided a far “better” (more perpendicular) direction of resistance during the early phase of the triceps’ range of motion, as compared with the standard Cable Pushdown they used. Yet, it appears the researchers were oblivious to this.

The researchers did not compare two exercises with an equal resistance curve. They thought the only difference between the two exercises was the position of the humerus / shoulder joint. In fact, they compared two exercises with two drastically different resistance curves, and a different shoulder position. Arguably, the more significant difference between the two exercises, was that the “overhead” version was early phase loaded (below-right), and the “neutral arm” version was mid-phase loaded (below-left).

This explains why the two “uni-articulate” heads (the Lateral Head and the Medial Head) of the triceps, both improved more with the “overhead” (“early phase loaded”) version, as compared with the “neutral arm” (mid phase loaded) version—even though these two heads do not cross the shoulder joint, and therefore do not change their function based on the position of the arm / shoulder.

It may ALSO explain why the Long Head developed better—especially if the degree of the elbow bend (in the early phase) was not monitored or measured, to ensure it was the same as the “neutral arm” version.

It should be noted that it’s easier to fully bend the elbows when the arms are down alongside the torso, as compared with when the arms are overhead. So, the degree of Long Head “elongation” could be greater with the arms down, if the elbows are not fully bent when the arms are overhead.

To reiterate, the problem with many of these studies is that the focus of the researchers is often only on variations that occur INSIDE the body. They are often oblivious to the variations that are occurring OUTSIDE the body–in the physics of the exercise itself.

In regard to this particular study, no doubt the researchers were fully aware of the musculoskeletal anatomy. They were certainly aware that the Long Head of the triceps changes its length when the position of the humerus / shoulder joint is altered.

They were likely also fully aware that a muscle benefits more from an exercise that is “early phase loaded”, as compared with an exercise that provide “mid-phase loading” or “late-phase loading”. However, they often do not know how to recognize the EXTERNAL (mechanical) factors that cause an exercise to provide more—or less—resistance, at different points in the arc of an exercise.

It is critically important for researchers to know how to IDENTIFY when the direction of resistance is perpendicular to a limb—versus parallel to a limb—because only then can the “resistance curve” of the exercise be identified. And only then can it be determined if it matches the strength curve of the target muscle. Otherwise, the exercise is compromised.

The conclusion reached by these researchers—that “Overhead Triceps Exercise are more productive than Neutral Arm Triceps Exercises”—ignores the significant difference in resistance curves, between the two exercises.

For the sake of perspective, consider the following. One of the exercises that has the most compromised resistance curve is the Dumbbell Triceps Kickback. It provides ZERO resistance in the early phase of the range of motion (when the elbow is most bent, and the triceps is strongest), and MAXIMUM resistance at the end of the range of motion (when the elbow is straight, and the triceps is weakest). The standard Cable Pushdown is slightly less compromised because it’s mostly mid-phase loaded.

So imagine if researches compared these two exercises, and concluded that Cable Pushdowns proved to be more productive than Dumbbell Kickbacks, and the reason is the position of the torso (one is upright and the other is bent over horizontally)—oblivious to the REAL reason one exercise is better than the other…namely, the resistance curve.

Obviously, the triceps have no way of recognizing (sensing) the position of the torso. The triceps ONLY recognize (sense) the resistance curve caused by the direction of resistance. They sense whether it’s early phase loaded, or mid phase loaded, or late phase loaded—and respond (benefit) accordingly.

In my book, I explain that it’s much better to use a neutral arm position as an optimal triceps exercise, provided you are using an ideal direction of resistance (which provides early phase loading). Then, you make sure that you are bending your elbows as much as possible at the beginning of the range of motion. This will allow you to get the most amount of triceps elongation without the discomfort caused by most overhead triceps exercises.

The two BEST triceps exercises are the Modified Cable Pushdown (using two pulleys…demonstrated above), and the Decline Dumbbell Triceps Extensions (shown below). I thoroughly explain the reasons for this in my book (also, see “The 16 Factors” on my website to understand the biomechanical criteria which determines what makes an exercise ideal, or varying degrees of compromised).

In the image below, you can see that the Long Head of my triceps has not “suffered” one bit, despite me NOT doing any overhead triceps extensions for the past 20 years. I only do the two exercises mention above.

Lastly, it’s worth asking “why DOES the Long Head of the Triceps cross the shoulder joint?”. Was it God’s intention that humans perform Overhead Triceps motions on a regular basis? Obviously, that is not the case. From an evolutionary standpoint, rarely (if ever) did early humans have to perform that type of movement.

The reason why the Long Head of the triceps crosses the shoulder joint, is for the same reason the Rectus femoris is the only part of the quadriceps that crosses the hip joint—to assist in a separate function.

For the Rectus femoris, that separate function is “hip flexion”. For the Long Head of the triceps, that second function is “humeral adduction” (pulling the arms downward…for example, when working the Lats).

The reason I mention this is because those two muscles get additional stimulation while assisting in those “other” functions, thereby relieving us of having to rely ONLY on “quadriceps exercises” or “triceps exercises” to optimize their development.

More importantly, in order to believe that we “should” do an Overhead Triceps exercise for maximum triceps benefit, we would also have to believe that in order to get maximum quadriceps benefit, we “should” do quadriceps exercises with a fully extended hip joint (so as to maximize the stretch of the Rectus femoris).

Obviously, that’s ridiculous. We can achieve maximum quadriceps development without fully extending the hip joint. Likewise, we can achieve maximum triceps development without fully extending the shoulder joint (i.e., positioning the arms overhead).

The post “Overhead Triceps Extensions are (NOT) Better Than Neutral Arms Triceps Extensions” appeared first on Doug Brignole.