BOTTICELLI AND GREATER GREECE

BOTTICELLI AND GREATER GREECE

Î ÏÏ

κοÏανÏία ÏοÏ

ÎÏελλή (Botticelli, De calumnia, 1494-1495, ΦλÏÏενÏία, ÎÏ

ÏίÏÏι)

Î ÏÏ

κοÏανÏία ÏοÏ

ÎÏελλή (Botticelli, De calumnia, 1494-1495, ΦλÏÏενÏία, ÎÏ

ÏίÏÏι)

Î Îιαβολή (ή ÏÏ ÎºÎ¿ÏανÏία) ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏελλή (ÎÏαλικά: La Calunnia di Apelle, είναι ÏÎ¯Î½Î±ÎºÎ±Ï Î¶ÏγÏαÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïον ÎÏÎ±Î»Ï ÎºÎ±Î»Î»Î¹ÏÎÏνη ÏÎ·Ï ÎναγÎννηÏÎ·Ï Î£Î¬Î½ÏÏο ÎÏοÏιÏÏÎλι. ΦιλοÏεÏνήθηκε ÏεÏίÏÎ¿Ï Ïο 1494 â 1495. ΣήμεÏα βÏίÏκεÏαι ÏÏη ÏÏ Î»Î»Î¿Î³Î® ÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Î¿Ï ÏÎµÎ¯Î¿Ï ÎÏ ÏίÏÏι ÏÏη ΦλÏÏενÏία, ÏÏην Î±Î¯Î¸Î¿Ï Ïα ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ αÏιεÏÏμÎνη ÏÏο μεγάλο Î´Î·Î¼Î¹Î¿Ï ÏγÏ. ΠΣάνÏÏο ÎÏοÏιÏÏÎλι άνÏληÏε Ïο θÎμα ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏÏ Îνα διάÏημο Ïίνακα ÏÎ¿Ï Îλληνα καλλιÏÎÏνη ÏÎ·Ï ÎµÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÏÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÏεÏιÏÎ´Î¿Ï ÎÏελλή, ÏÏÏÏ Î±Ï ÏÏÏ ÏεÏιγÏάÏηκε αÏÏ Ïο ÎÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ¹Î±Î½Ï ÏÏον ÏÎÏαÏÏο ÏÏμο αÏÏ Ïα ογδÏνÏα ÏÏζÏμενα ÎÏγα ÏÎ¿Ï , ÏÏην ÏÏαγμαÏεία ÏÎ¿Ï Î ÎµÏὶ Ïοῦ μὴ ῥᾳδίÏÏ ÏιÏÏεÏειν διαβολá¿.ΠλÏÎ³Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿ ÎÏÎµÎ»Î»Î®Ï ÏιλοÏÎÏνηÏε Ïον Ïίνακα Î±Ï ÏÏ Î®Ïαν ÎÎ½Î±Ï ÏÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Î½Î± ÏεÏιγÏάÏει Ïα ÏÏ Î½Î±Î¹ÏθήμαÏα θλίÏÎ·Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ οÏÎ³Î®Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿ Î¯Î´Î¹Î¿Ï ÎνιÏÏε ÏÏαν καÏηγοÏήθηκε άδικα, αÏÏ Îναν ανÏαγÏνιÏÏή ÏÎ¿Ï , Ïον ÎνÏίÏιλο, για Ïη δήθεν ÏÏ Î¼Î¼ÎµÏοÏή ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏο Îγκλημα ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏ Î½ÏμοÏÎ¯Î±Ï ÎºÎ±Ïά ÏÎ¿Ï Î¦Î±ÏÎ±Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎλληνιÏÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎιγÏÏÏÎ¿Ï , Î ÏÎ¿Î»ÎµÎ¼Î±Î¯Î¿Ï Îâ ÏÎ¿Ï Î£ÏÏήÏα. ÎÏαν αÏοδείÏÏηκε η αθÏÏÏηÏά ÏÎ¿Ï , αÏοÏάÏιÏε να μεÏαÏÎÏει Ïο ÏÏοÏÏÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î²Î¯Ïμα ÏÏον Ïίνακα Î±Ï ÏÏ. Το ÎÏγο δεν ÏÏζÏÏαν ÏÏÎ¹Ï Î¼ÎÏÎµÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏοÏιÏÏÎλι. ΩÏÏÏÏο η ÏεÏιγÏαÏή ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ¹Î±Î½Î¿Ï ÎµÎ¯Ïε μεÏαÏÏαÏÏεί ÎµÏ ÏÎÏÏ. ΣÏον Î´Î¹ÎºÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ïίνακα, ο αναγεννηÏιακÏÏ Î¶ÏγÏάÏÎ¿Ï Î´Î¹Î±ÏήÏηÏε Ïο ÏÎºÎ·Î½Î¹ÎºÏ ÏÏήÏιμο ÏÏν μοÏÏÏν αÏÏ Ïην ÏεÏιγÏαÏή ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ¹Î±Î½Î¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ δημιοÏÏγηÏε Îνα ÏεÏίÏεÏνα ÏÏολιÏμÎνο αÏÏιÏεκÏÎ¿Î½Î¹ÎºÏ ÏÏνÏο για εκείνεÏ.

ÎÎ Î ÎÎΣΩ ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎΡÎ[10]: ÎÏμα ÏÏ ÎºÎ¿ÏανÏÎ¯Î±Ï Ï ÏήÏξε κάÏοÏε και ο ÏεÏίÏÎ·Î¼Î¿Ï Î¶ÏγÏάÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎλληνιÏÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÏεÏιÏÎ´Î¿Ï ÎÏελλήÏ, ο οÏÎ¿Î¯Î¿Ï ÎºÎ±ÏηγοÏήθηκε αÏÏ ÎºÎ¬Ïοιον ομÏÏεÏÎ½Ï ÏÎ¿Ï , Ïον ÎνÏίÏιλο, ÏÏÏ ÏÏ Î½ÏμÏÏηÏε ÏÏο ÏÎ»ÎµÏ ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î¥ÏάÏÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï Î¤ÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎεοδÏÏα ενανÏίον ÏÎ¿Ï Î²Î±Ïιλιά ÏÎ·Ï ÎιγÏÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÎµÏ ÎµÏγÎÏη ÏÎ¿Ï , Î ÏÎ¿Î»ÎµÎ¼Î±Î¯Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ. Î ÏεÏιÏÎÏεια ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏελλή Îληξε γÏήγοÏα καθÏÏ Î±ÏοδείÏθηκε ÏÏÏ Î´ÎµÎ½ είÏε εÏιÏκεÏÏεί ÏοÏÎ ÏÎ¿Ï Ïην ΤÏÏο. ÎÏÎ ÏÏι ÏαίνεÏαι ÏμÏÏ Ïον ÏÏιγμάÏιÏε ÏÏÏο ÏÎ¿Ï Î¸ÎληÏε να αÏοÏÏ ÏÏÏει Ïην οδÏνη ÏÎ¿Ï Î¶ÏγÏαÏίζονÏÎ±Ï Îνα ÏÎ¿Î»Ï ÏÏνθεÏο ÎÏγο με ÏίÏλο «Îιαβολή». Î ÏÎ¯Î½Î±ÎºÎ±Ï Î´Ï ÏÏÏ ÏÏÏ Î´Îµ διαÏÏθηκε. ÎιÏÎ½ÎµÏ Î±ÏγÏÏεÏα ÏμÏÏ Î¿ ΣάνÏÏο ÎÏοÏιÏÏÎλλι εμÏÎ½ÎµÏ ÏμÎÎ½Î¿Ï Î±ÏÏ ÏÎ¹Ï Î»ÎµÏÏομεÏÎµÎ¯Ï ÏεÏιγÏαÏÎÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏÎ³Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏελλή ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿ ÎÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ¹Î±Î½ÏÏ Î±Î½ÎÏεÏε ÏÏην ÏÏαγμαÏεία ÏÎ¿Ï , «ΠεÏὶ Ïοῦ μὴ ῥᾳδίÏÏ ÏιÏÏεÏειν διαβολá¿Â», καÏάÏεÏε να Ïον αναÏαÏαγάγει και να αÏοδÏÏει με μεγάλη ÏαÏαÏÏαÏικÏÏηÏα Ïο δÏάμα ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏÏÎ±Î¯Î¿Ï Î¶ÏγÏάÏÎ¿Ï Î¼ÎµÏαÏÎÏονÏÎ¬Ï Ïο ÏÏην εÏοÏή ÏÎ¿Ï .

O ÎÎΣΣÎÎÎÎÎÎÎΥΣ ÎÎÎÎ. ÎÎÎÎΣ ΣΤÎÎ 'ÎÎΤΡÎÎΠΤΩΠÎÎÎΩÎ' ΤÎÎ¥ ÎÎ ÎΤÎΤΣÎÎÎÎ (Sandro Botticelli, âAdoration of the Magiâ, 1475-1476. Uffizi, Italy)

ÎκÏιβÏÏ Î±ÏιÏÏεÏά ÏÎ¿Ï ÎεοδÏÏÎ¿Ï Îαζή [Î Î. ÎαζήÏ, ο εÏονομαζÏÎ¼ÎµÎ½Î¿Ï ÎεÏÏαλονικεÏÏ Î® Thessalonicensis ÏÏα λαÏινικά, ήÏαν ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î±Ï Î¿Ï Î¼Î±Î½Î¹ÏÏήÏ, μεÏαÏÏαÏÏÎ®Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏιÏÏοÏÎÎ»Î¿Ï Ï, εÏιÏÏÎ®Î¼Î¿Î½Î±Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ λÏÎ³Î¹Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï 15Î¿Ï Î±Î¹ÏνοÏ, διακÏίθηκε ÏÏην λεγομÎνη Î ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎÎÎÎÎ ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎÎΣÎ!] ÏÏÎκεÏαι ο ÏοÏηγÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ïίνακα, Lorenzo Medici, ÏÏα μαÏÏα και δεξιά ο Î¯Î´Î¹Î¿Ï Î¿ ζÏγÏάÏÎ¿Ï Sandro Botticelli με ÏοÏÏοκαλί μανδÏα. ÎÎ½Ï Î¿ Î³Î¹Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î Î¹ÎÏÏο ÏÏ Î´ÎµÏÏεÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ¬Î³Î¿Ï Î³Î¿Î½Î±Ïίζει ÏÏο κÎνÏÏο ÏÎ·Ï ÎµÎ¹ÎºÏÎ½Î±Ï Î¼Îµ κÏκκινο μανδÏα, δίÏλα ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ ο αδεÏÏÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î¤Î¶Î¹Î¿Î²Î¬Î½Î¹ ÏÏ ÏÏίÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ¬Î³Î¿Ï ÎµÎ½Ï Î±ÏεικονίζονÏαι και Ïα εγγÏνια ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏζιμο, Î¤Î¶Î¿Ï Î»Î¹Î¬Î½Î¿ και ÎοÏÎνÏζο. Îι ÏÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÎÎδικοι ÏÎ¿Ï ÏαÏÎ¿Ï Ïίαζαν ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÎÎ¬Î³Î¿Ï Ï ÎµÎ¯Ïαν ήδη Ïεθάνει Ïην ÏÏιγμή ÏÎ·Ï Î´Î·Î¼Î¹Î¿Ï ÏÎ³Î¯Î±Ï Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Ïίνακα και η ΦλÏÏενÏία ÎµÎºÏ Î²ÎµÏνάÏο αÏÏ Ïον ÎοÏÎνÏζο, ÏÏοÏανÏÏ Î¼ÎµÎ³Î¬Î»Î¿ Î¸Î±Ï Î¼Î±ÏÏή ÏÎ¿Ï Îαζή, ÏÎ¿Ï Î²ÏιÏκÏÏαν ακÏιβÏÏ ÏίÏÏ Î±ÏÏ Ïην ÏλάÏη ÏÎ¿Ï .-------------------------------------------------------------------Immediately to the left of Theodor Gaza stands the client of the painting, Lorenzo Medici, in black, and to the right is the painter Sandro Botticelli himself, in an orange cloak. While his son Piettro as the second Magi kneels in the center of the picture in a red cloak, next to him are his brother Giovanni as the third Magi and Cosimo's grandchildren Giuliano and Lorenzo pictured. Three Mediciâs presenting three Magiâs had already died at the time of creation of this painting, and Florence was ruled by Lorenzo, obviously very fond of Gaza, located just behind his back.

.. From 1440 to 1449, as the successor of the Byzantine Nicholas Secundinus, Gaza taught Greek while studying at Ferrara. His service in that city was the first sign of the dispersal of Greek learning in the European West, as it took place only a few decades after Chrysoloras' first systematic lectures on the Greek language in the Renaissance at a Florentine Studium. Gaza's lectures were so successful that in1449 he was appointed the first rector of the University of Ferrara after its renewal by Duke Lionello d'Este.Gaza's surviving inaugural speech, âOn Greek Writersâ (âDe litteris graecisâ), is probably the earliest surviving inaugural presentation on the importance of Greek studies held in Italy by an emigrant Byzantine scholar. Manuel Chrysoloras' earlier presentation in Florence has not been preserved. In hispresentation, Gaza emphasized that the ancient Romans also had extensive knowledge of Greek literature and its invaluable value for active participation in political life. According to Gaza, leading Roman political figures sent their sons to study in Greece. SOURCE: The Byzantine Renaissance as the predominant source and impetus for the Italian Renaissance - Theodore Gaza in Mantua, Ferrara, Rome and Naples and Nicolaos Leonicos Tomeos in Venice, Florence and Padua - <https://www.researchgate.net/.../3516... ΠΣΧÎÎΠΤΩΠÎÎÎÎΩΠ- ΡÎΦÎÎÎ -->

Î ÎÏ Î¶Î±Î½Ïινή [ΠαλαιολÏγεια] ÎναγÎννηÏη ÏÏ Î· ÎºÏ ÏίαÏÏη Ïηγή και ÏθηÏη για Ïην ÎÏαλική ÎναγÎννηÏη[20]

«ΠÎÏ Î¶Î±Î½Ïινή ÎναγÎννηÏη ÏÏ Ïο κοÏÏ Ïαίο θεμÎλιο ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏÎ±Î»Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎναγÎννηÏηÏ: ÎεÏδÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ±Î¶Î®Ï ÏÏην ÎάνÏοβα, ΦεÏάÏα, ΡÏμη και ÎάÏολη και ÎικÏÎ»Î±Î¿Ï ÎεÏÎ½Î¹ÎºÎ¿Ï ÎÏμεÏÏ ÏÏην ÎενεÏία, ΦλÏÏενÏία και ΠάνÏοβα" ÎÏο ακÏμη άÏομα ÏÏν οÏοίÏν η άÏιξη ÏÏην ÎÏαλία βοήθηÏε ÏάÏα ÏÎ¿Î»Ï Î½Î± καÏÎµÏ Î¸Ïνει Ïον Ï ÏάÏÏονÏα ÎνθÏÏÏιÏÎ¼Ï Î±ÏÏ Î±Ï Ïήν Ïην αÏÏική ÎμÏαÏη ÏÎ¿Ï ÏηÏοÏÎ¹ÎºÎ¿Ï Ï ÏήÏξαν οι Î²Ï Î¶Î±Î½Ïινοί καθηγηÏÎÏ ÎεÏδÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ±Î¶Î®Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÎικÏÎ»Î±Î¿Ï ÎεÏÎ½Î¹ÎºÎ¿Ï ÎÏμεÏÏ, ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ οι δÏο ÏÏοήδÏÎµÏ Ïαν εδÏÏν αÏιεÏÏμÎνÏν ÏÏην ελληνική ÏιλοÏοÏία Ïε ÏανεÏιÏÏήμια ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏÎ±Î»Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï Î§ÎµÏÏονήÏÎ¿Ï . ΠκαÏιÎÏα ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î¼ÏοÏεί να είναι διÏαÏμÎνη Ïε διαÏοÏεÏικÎÏ Î¼ÎµÎ³Î¬Î»ÎµÏ ÏάÏειÏ. ÎÏιÏμÎνα ÏÏάδια είναι ανεÏαÏκÏÏ Î³Î½ÏÏÏά λÏÎ³Ï ÎµÎ»Î»ÎµÎ¯ÏεÏÏ ÏÏÏÏν ÏÏιν αÏÏ Ïην ÏÏÏÏη ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏνÏÏανÏÎ¹Î½Î¿Ï ÏÏλεÏÏ ÏÏα ÏÎ¿Ï Ïκικά ÏÎÏια Ïο 1453. Îλλα, αÏκεÏά μεγαλÏÏεÏÎ·Ï Î´Î¹Î¬ÏÎºÎµÎ¹Î±Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ Ïιο ÏημανÏικά για Ïην ιÏαλική ÎναγÎννηÏη, ÏαÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¹Î¬Î¶Î¿Ï Î½ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î²Ï Î¶Î±Î½ÏινοÏÏ Î»ÏÎ³Î¹Î¿Ï Ï ÏÏ Î»ÎκÏοÏÎµÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏαÏÏολοÏνÏαι Ïε Ïλην Ïην ÎÏαλία, Ïην εÏοÏή ÏÎ¿Ï Î±Ï Ïή η ÏÏÏα Îμελλε να ÏÏάÏει ÏÏο αÏÏγειο ÏÎ·Ï ÏÎ®Î¼Î·Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏ Ïο κÎνÏÏο ÏÎ¿Ï ÎνθÏÏÏιÏμοÏ.Π«ÎνθÏÏÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎναγεννήÏεÏÏ», ÎÎ½Î±Ï Î¬Î½Î¸ÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Îµ ÎµÏ ÏÏ Ïεδίο ÏκÎÏεÏν και ÏÏάξεÏν, ÎÎ½Î±Ï ÏαγκοÏÎ¼Î¯Î¿Ï ÏÎ®Î¼Î·Ï ÏÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏ Î½Î®Î¸ÏÏ ÎµÏαÏμÏζεÏαι ÏÏον ιÏÎ±Î»Î¹ÎºÏ Î¿Ï Î¼Î±Î½Î¹ÏÎ¼Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ Ïην αναγÎννηÏη, ÏÏοÏανÏÏ Î±Î½Î®ÎºÎµÎ¹ ÏÏÏÏα και κÏÏια ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î²Ï Î¶Î±Î½ÏινοÏÏ Î¼ÎµÎ»ÎµÏηÏÎÏ.ÎÏÏÏ ÏαίνεÏαι ξεκάθαÏα εδÏ, η Ïίζα ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÎ·Ï Î¿Ï ÏÎ¯Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Â«ÎνθÏÏÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎναγεννήÏεÏÏ» ÎγκειÏαι ÏÏην ÏÏαγμαÏικÏÏηÏα ÏÏην Îλληνική και ÎÏ Î¶Î±Î½Ïινή «εγκÏκλειο Ïαιδεία», ÏÏÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ Ïην «ÏÎ¿Î»Ï Î¸ÎµÎ¼Î±Ïική θεÏÏηÏη», κÏÏια ÏαÏακÏηÏιÏÏικά ενÏÏ ÎµÎºÏÎ±Î¹Î´ÎµÏ ÏÎ¹ÎºÎ¿Ï ÏÏ ÏÏήμαÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï Î±Ï ÏοκÏαÏοÏÎ¯Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÏÏοÏοÏοÏÏε Ïε ÏÎ»Î¿Ï Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÎºÎ»Î¬Î´Î¿Ï Ï ÏÏην ανεÏÏÏ Î³Î¼Îνη ÎÏ ÏÏÏη και Ïην ÎεÏÏγειο για ÏεÏιÏÏÏÏεÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î±ÏÏ Îνδεκα αιÏνεÏ, καÏά Ïον ίδιο ÏÏÏÏο ÏÎ¿Ï Ïο ΠανεÏιÏÏήμιο ÏÎ·Ï ÎαγναÏÏÎ±Ï Î® ΠανδιδακÏήÏιο ή ÎÎ±Î¸Î¿Î»Î¹ÎºÏ Î Î±Î½/μιο ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏνÏÏανÏÎ¹Î½Î¿Ï ÏÏλεÏÏ, η ÎδÏα ÏÎ·Ï Î¿ÏÎ¿Î¯Î±Ï ÎµÏÏημαÏοδοÏείÏο αÏÏ Ïον ΣÎÏβο ΤÏάÏο ÎÏÏÎ¿Ï Ïον ÎδÏναμο (!?)[ΠΣÏÎÏÎ±Î½Î¿Ï ÎÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ ÎÏοÏÏαν, γνÏÏÏÏÏ ÏÏ ÎÏοÏÏαν ο ÎÏÏÏ ÏÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÏα ελληνικά ÏÏ Î£ÏÎÏÎ±Î½Î¿Ï ÎÎ¿Ï Ïάν, ήÏαν βαÏÎ¹Î»Î¹Î¬Ï ÏÎ·Ï Î£ÎµÏÎ²Î¯Î±Ï Î±ÏÏ ÏÎ¹Ï 8 ΣεÏÏεμβÏÎ¯Î¿Ï 1331 και ÎÏ ÏοκÏάÏοÏÎ±Ï Î£ÎÏβÏν, ÎλλήνÏν, ÎÎ¿Ï Î»Î³Î¬ÏÏν, ÎλάÏÏν και ÎλβανÏν αÏÏ ÏÎ¹Ï 16 ÎÏÏÎ¹Î»Î¯Î¿Ï 1346 μÎÏÏι Ïον θάναÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ], ήÏαν Ïο κοÏÏ Ïαίο ίδÏÏ Î¼Î± για ÏÏεδÏν μια ÏιλιεÏία ÏÏιν αÏÏ Ïην ίδÏÏ Ïη ÏÏν ÏανεÏιÏÏημίÏν ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏολÏνια, ÏÎ·Ï Î Î¬Î½ÏοβαÏ, ÏÎ·Ï Î£Î¿ÏβÏÎ½Î½Î·Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÎ·Ï ÎξÏÏÏδηÏ.ÎÏÏ ÎµÎºÎµÎ¯ ακÏιβÏÏ ÏÏοÎÏÏεÏαι η ιÏαλική ÎναγÎννηÏη. ------------------------------------------------------------------- The Byzantine Renaissance as the predominant source and impetus for the Italian Renaissance âThe Byzantine Renaissance as the premier foundation of the Italian Renaissance: Theodore Gaza in Mantova, Ferrara, Rome and Naples and Nikolaos Leonikostomeos in Venice, Florence and Paduaâ Two more persons whose arrival in Italy helped immensely to direct the existing Humanism from its original rhetorician emphasis were Byzantine professors Theodoros Gaza and Niccolo Leonico Tomeo, who both chaired a Greek philosophy at universities around the peninsula. Their careers may be divided into different large phases. Certain stages are insufficiently known due to a lack of resources before thefall of the Byzantine capital Constantinople into Turkish hands in 1453. Other, considerably longer and more important for the Italian Renaissance, represents Byzantine scholars as lecturers employed throughout Italy, at the time when this country was about to reach the height of its fame as a Humanism center.The âRenaissance Manâ, a man with broad scopes of thoughts and deeds, a world-renowned term usually applied to Italian Humanism and Renaissance, obviously belongs first and foremost to Byzantine scholars.As clearly visible here, the root of the term and essence of a âRenaissance Manâ actually is in Greek and Byzantine âenkyklios paideiaâ, as âall embracing thoughtfulnessâ, main characteristics of an educational system of the empire that was leading in all terms and most developed in Europe and the Mediterranean for more than eleven centuries, in as much as Constantinopleâs Catholicon University, the headquarters of which were financed by Serbian Tsar UroÅ¡ the Weak (!?), was the leading one for nearly a millennium before Bologna, Padua, Sorbonne and Oxford universities were established.That is exactly where an Italian Renaissance is coming from. Predrag MiloÅ¡eviÄ -->

ΠΠΡΩΤÎÎÎÎÎΣ ÎΩÎΡÎΦÎÎΩΠΤÎÎ ÎÎÎΥΣΠ(ÎΡÎΠΤÎÎ¥ Giorgio Vasari, 1540s. Vasari's House, Arezzo)[1000]

ΠζÏγÏάÏÎ¿Ï Î ÏÏÏογÎÎ½Î·Ï Î®Ïαν διάÏÎ·Î¼Î¿Ï Î³Î¹Î± Îναν Ïίνακα ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏεικÏνιζε Ïον ήÏÏα ÎÎ¬Î»Ï Ïο ÏÏην ΡÏδο, για Ïην ολοκλήÏÏÏη ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿ÏÎ¿Î¯Î¿Ï ÎµÏγάÏÏηκε εÏÏά ÏÏÏνια. ÎÏαν μάλιÏÏα ο ÏÎ¯Î½Î±ÎºÎ±Ï Î²ÏιÏκÏÏαν ÏÏο ÏÎµÎ»Î¹ÎºÏ ÏÏάδιο, Ïο 305-304 Ï.Χ., ο ÎημήÏÏÎ¹Î¿Ï Î Î¿Î»Î¹Î¿ÏκηÏÎ®Ï ÎµÎ¾ÎµÏÏÏάÏÎµÏ Ïε ενανÏίον ÏÎ·Ï Î¡ÏÎ´Î¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹, αÏÏ ÏεβαÏÎ¼Ï ÏÏÎ¿Ï Îνα ÏÏÏο εξαιÏεÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÎÏγο ÏÎÏνηÏ, διÎÏαξε Ïα ÏÏÏαÏεÏμαÏά ÏÎ¿Ï Î½Î± μην ÏÏ ÏÏολήÏÎ¿Ï Î½ Ïην ÏÏλη. ÎαÏά Ïη διάÏκεια ÏÎ·Ï ÏολιοÏκίαÏ, ο καλλιÏÎÏÎ½Î·Ï ÏÏ Î½ÎÏιÏε να εÏγάζεÏαι αμÎÏιμνοÏ, λÎγονÏÎ±Ï ÏαÏακÏηÏιÏÏικά ÏÏι ο βαÏÎ¹Î»Î¹Î¬Ï Îκανε ÏÏλεμο ενανÏίον ÏÎ·Ï Î¡ÏÎ´Î¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÏι ενανÏίον ÏÏν ÏεÏνÏν. Î ÎημήÏÏÎ¹Î¿Ï ÎθεÏε Ï ÏÏ ÏÏοÏÏηÏη Ïον Î ÏÏÏογÎνη, για να διαÏÏαλίÏει Ïη ÏÏμαÏική ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÎºÎµÏαιÏÏηÏα. Î¥ÏÏ Î±Ï ÏÎÏ ÏÎ¹Ï ÏÏ Î½Î¸Î®ÎºÎµÏ Î¿ καλλιÏÎÏÎ½Î·Ï Î¶ÏγÏάÏιÏε Ïον ÏεÏίÏημο ÎναÏÎ±Ï Ïμενο ΣάÏÏ ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï . ................. ..................................................................................................... ΣÏο ÎÏγο Î¦Ï Ïική ÎÏÏοÏία (Naturalis Historia) ÏÎ¿Ï Î Î»Î¹Î½Î¯Î¿Ï , ο Î ÏÏÏογÎÎ½Î·Ï Î±Î½Î±ÏÎÏεÏαι ÏÏ Î¿ Ïιο διάÏÎ·Î¼Î¿Ï Î¶ÏγÏάÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏεÏάÏÏÎ¿Ï Î±Î¹Ïνα Ï.Χ. μαζί με Ïον ÎÏελλή, ÏεÏιγÏάÏεÏαι δε ÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î»Î»Î¹ÏÎÏÎ½Î·Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î´Î¯Î½ÎµÎ¹ ιδιαίÏεÏη ÏÏοÏοÏή ÏÏην λεÏÏομÎÏεια. ΣÏμÏÏνα με Ïον Πλίνιο, ÏÏαν ο Î ÏÏÏογÎÎ½Î·Ï Î¶ÏγÏάÏιζε Ïο Ïιο διάÏημο ÎÏγο ÏÎ¿Ï - ο ÎºÏ Î½Î·Î³ÏÏ ÎÎ±Î»Ï ÏÏÏ ÏÏ Î½Î¿Î´ÎµÏ ÏÎ¼ÎµÎ½Î¿Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïον ÏκÏλο ÏÎ¿Ï - δοÏλεÏε αÏÏαμάÏηÏα Ïε μία λεÏÏομÎÏεια, ÏάÏνονÏÎ±Ï Îναν ÏÏÏÏο αÏεικονίÏεÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏÏÎ¿Ï Î³ÏÏÏ Î±ÏÏ Ïο ÏÏÏμα ÏÎ¿Ï ÏκÏÎ»Î¿Ï , ÎÏÏ ÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ¾Î¿ÏγίÏÏηκε και ÎÏιξε Îνα ÏÏÎ¿Ï Î³Î³Î¬Ïι ÏÏην εικÏνα. ÎÏ ÏÏ Î¬ÏηÏε ÏÏι ο Botticelli ίÏÏÏ Î¸Î± είÏε οÏίÏει ÏÏ 'Îνα ίÏνοÏ', ÏÏο οÏοίο ο Î ÏÏÏογÎÎ½Î·Ï Î±Î½Î±Î³Î½ÏÏιÏε ÏÏι εÏιÏÏ Î³ÏάνεÏο ÏÏ Ïαία Ïο αÏοÏÎλεÏμα για Ïο οÏοίο είÏε ÏÏοÏÏαθήÏει ÏÏÏο κοÏιαÏÏικά. ÎÏ ÏÏ Ïο εÏειÏÏδιο, μαζί με άλλα ανÎκδοÏα ÏÎ¿Ï Î Î»Î¹Î½Î¯Î¿Ï Î³Î¹Î± ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î¼ÎµÎ³Î¬Î»Î¿Ï Ï Î¶ÏγÏάÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÎ·Ï Î±ÏÏαιÏÏηÏαÏ, αÏεικονίζεÏαι Ïε μια ÏοιÏογÏαÏία ζÏγÏαÏιÏμÎνη αÏÏ Ïον Vasari ÏÏην οικία ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏο ÎÏÎÏÏο. ........ "ÎιαÏί αÏλÏÏ ÏίÏνονÏÎ±Ï Îνα ÏÏÎ¿Ï Î³Î³Î¬Ïι γεμάÏο με διαÏοÏεÏικά ÏÏÏμαÏα ÏÏον ÏοίÏο, Î´Î·Î¼Î¹Î¿Ï ÏγείÏε ÎνανλεκÎ, ÏÏον οÏοίο μÏοÏείÏε να δείÏε μια ÏμοÏÏη αÏεικÏνιÏη ÏοÏÎ¯Î¿Ï .' ΦαίνεÏαι ÏÏι με Î±Ï ÏÎÏ ÏÎ¹Ï Î»ÎξειÏ, ÏÎ¹Ï Î¿ÏÎ¿Î¯ÎµÏ ÏαÏαθÎÏει με εÏιμÎλεια ο ÎεονάÏνÏο ÏÏο Libro di Pittura, ο Botticelli δικαιολογεί Ïην αδιαÏοÏία ÏÎ¿Ï Î³Î¹Î± Ïην ζÏγÏαÏική ÏοÏÎ¯Î¿Ï . Το ÏÏÏÏÏÏÏ Ïο κείμενο ÏÎ¿Ï da Vinci ÎÏει ÎÏει Ïαθεί, αλλά ο κÏÎ´Î¹ÎºÎ±Ï ÏÏην ÎÏοÏÏολική Îιβλιοθήκη ÏÎ¿Ï ÎαÏÎ¹ÎºÎ±Î½Î¿Ï ÏÏην οÏοία Ïο αÏÏÏÏαÏμα ÎÏει αναÏαÏαÏθεί θεÏÏείÏαι ÏÎ¿Î»Ï Î±Î¾Î¹ÏÏιÏÏη. Î Î±Ï 'Ïλα Î±Ï Ïά, ο Horne εξÎÏÏαÏε αμÏιβολία ÏÏ ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ïην ειλικÏίνεια ÏÎ·Ï Î´Î·Î»ÏÏεÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏοÏιÏÏÎλι, ÏÎ¿Ï , καÏά Ïη γνÏμη ÏÎ¿Ï , δεν μÏοÏοÏÏε να διαβαÏÏεί με οÏοιονδήÏοÏε άλλο ÏÏÏÏο εκÏÏÏ Î±ÏÏ "ÏαÏάδοξο ÏÏÏ Î»" ÏαÏακÏηÏιÏÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î»Î»Î¹ÏÎÏνη ÏÎ·Ï Î¦Î»ÏÏενÏίαÏ. ΣÏην ÏÏαγμαÏικÏÏηÏα, είναι αÏίθανο ÏÏι ο ÎÏοÏιÏÏÎλι θα μÏοÏοÏÏε ÏοβαÏά να ÏÏολιάÏει Ïην ζÏγÏαÏική ÏοÏÎ¯Î¿Ï Î¼Îµ Î±Ï ÏοÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ αν ÏÏηÏιμοÏοιοÏÏε Ïην ακÏαία εικÏνα ÏÎ¿Ï Î»ÎµÎºÎ ÏÏον ÏοίÏο ÏÏ Ï ÏοκαÏάÏÏαÏο ÏÎ¿Ï 'ÏμοÏÏÎ¿Ï ÏοÏÎ¯Î¿Ï ' θα ήÏαν μÏνο Ïε ÏÏÎÏη με Ïο ανÎκδοÏο ÏÎ¿Ï Î Î»Î¹Î½Î¯Î¿Ï Î³Î¹Î± Îναν αÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Ïιο διάÏÎ·Î¼Î¿Ï Ï Î¶ÏγÏάÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÎ·Ï Î±ÏÏαιÏÏηÏαÏ, Ïον Î ÏÏÏογÎνη ...

ÎÎ½Î±Î´Ï Î¿Î¼Îνη ÎÏÏοδίÏη & Botticelli[1100]

MFA AC. NR. 1982.286, ÏÏ

ÏÏεÏιÏθείÏα με Ïην ÎλεοÏάÏÏα η οÏοία αναδÏ

ομÎνη ÏÏ

νανÏά Ïον ÎνÏÏνιο, Ïην ÎÏία Πελαγία - ÎαÏγαÏίÏα ÎºÎ»Ï (γενειοÏÏÏο ή μή)

MFA AC. NR. 1982.286, ÏÏ

ÏÏεÏιÏθείÏα με Ïην ÎλεοÏάÏÏα η οÏοία αναδÏ

ομÎνη ÏÏ

νανÏά Ïον ÎνÏÏνιο, Ïην ÎÏία Πελαγία - ÎαÏγαÏίÏα ÎºÎ»Ï (γενειοÏÏÏο ή μή)

ÎναδÏ

ομÎνη ÏοÏ

ÎεοÏίλοÏ

ÎναδÏ

ομÎνη ÏοÏ

ÎεοÏίλοÏ

Î ÏοÏÏÏογÏαÏία νεÏÎ±Ï Î³Ï Î½Î±Î¯ÎºÎ±Ï[1200]Portrait of a Young Woman is a painting which is commonly believed to be by the Italian Renaissance painter Sandro Botticelli, executed between 1480 and 1485. The woman is shown in profile but with her bust reveal a cameo medallion she is wearing around her neck. The medallion is a copy in reverse of "Nero's Seal" (**), a famous antique carnelian representing Apollo and Marsyas, which belonged to Lorenzo de' Medici . The art historian Aby Warburg first suggested the painting was an idealised portrait of Simonetta Vespucci. This challenged a previous interpretation, put forward by German scholars, according to which the painting describes an ideally beautiful young woman mythologised as a nymph or goddess, a view reflected in the title given it by the Städel. It belongs to a group of such paintings by Botticelli or his workshop. Art historian Emanuele Lugli has suggested that the three "tassels" of hair at the center of the painting represents downward flames, symbolising the love that onlookers ought to experience when looking at the portrait since, in the Renaissance it was thought that "hair inflames desire.

(**)In the story about Apollo and Marsyas, a Phrygian mortal named Marsyas, who may have been a satyr, ( satyrs are one of a class of lustful, drunken woodland gods. In Greek art they were represented as a man with a horse's ears and tail, but in Roman representations as a man with a goat's ears, tail, legs, and horns.) who boasted about his musical skill on the aulos. The aulos was a double-reed flute. The instrument has multiple origin stories. In one, Marsyas found the instrument after Athena had abandoned it. In another origin story, Marsyas invented the aulos. Cleopatra's father evidently also played this instrument, since he was known as Ptolemy Auletes. Marsyas claimed he could produce music on his pipes far superior to that of the cithara-plucking Apollo. Some versions of this myth say it was Athena who punished Marsyas for daring to pick up the instrument she had discarded (because it had disfigured her face when she puffed out her cheeks to blow). In response to the mortal braggadocio, different versions hold that either the god challenged Marsyas to a contest or Marsyas challenged the god. The loser would have to pay a gruesome price. In their music contest, Apollo and Marsyas took turns on their instruments: Apollo on his stringed cithara and Marsyas on his double-pipe aulos. Although Apollo is the god of music, he faced a worthy opponent: musically speaking, that is. Were Marsyas truly an opponent worthy of a god, there would be little more to be said. The deciding judges are also different in different versions of the story. One holds that the Muses judged the wind vs. string contest and another version says it was Midas, king of Phrygia. Marsyas and Apollo were almost equal for the first round, and so the Muses judged Marsyas the victor, but Apollo had not yet given up. Depending on the variation you are reading, either Apollo turned his instrument upside down to play the same tune, or he sang to the accompaniment of his lyre. Since Marsyas could neither blow into the wrong and widely separate ends of his aulos, nor singâeven assuming his voice could have been a match for that of the god of musicâwhile blowing into his pipes, he did not stand a chance in either version. Apollo won and claimed the prize of the victor that they had agreed upon before beginning the contest. Apollo could do whatever he wished to Marsyas. So Marsyas paid for his hubris by being pinned to a tree and flayed alive by Apollo.The short story is ; `Nero`s seal` was a hidden message given by Botticelli ; `do not challenge god` Sandro Botticelli was fundamentalist religious man of early Renausans .

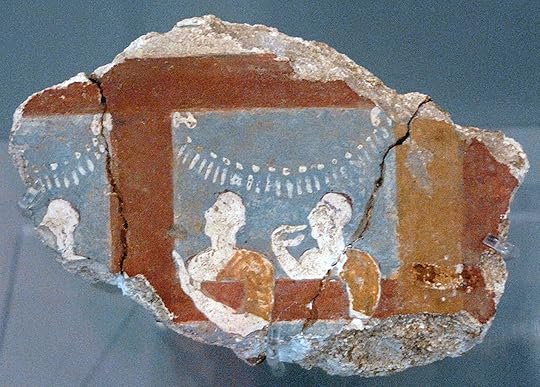

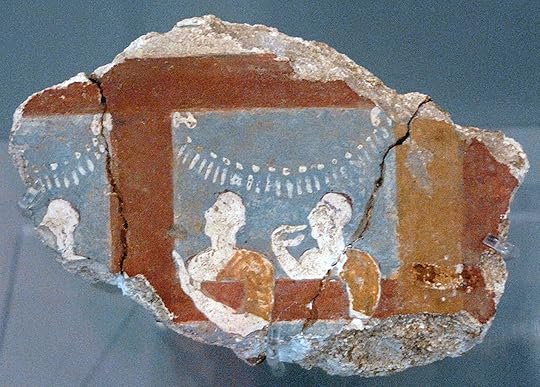

'ÎÎ¥ÎÎÎÎÎΣ ΣΤΠΠÎΡÎÎΥΡÎ': ÎΠΠΤÎÎ ÎÎÎΩÎΤΠ& ÎÎ¥ÎÎÎÎÎΠΤÎÎΧÎÎΡÎΦΠΣΤÎÎ ÎÎ ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎÎΥΨΠΤÎΣ ÎÎÎÎÎΤÎÎÎÎΣ ÎΠΠΤÎÎ BOTICELLI .. ÎΤÎÎ Î ÎÎ¥ÎÎÎÎÎ Î ÎΡÎÎÎÎ ÎÎ ÎÎΡΡÎΣ ΤΠ'ÎΡÎÎ'![1300] âWomen in a loggiaâ from ramp house deposit, Mycenae 'ÎÏ

Î½Î±Î¯ÎºÎµÏ ÏÏο θεÏÏείο' ÎÏ

κήναι

âWomen in a loggiaâ from ramp house deposit, Mycenae 'ÎÏ

Î½Î±Î¯ÎºÎµÏ ÏÏο θεÏÏείο' ÎÏ

κήναι

Botticelliâs Portrait of Smeralda Bandinelli, c147l, âbreaking the frameâ.

Botticelliâs Portrait of Smeralda Bandinelli, c147l, âbreaking the frameâ.

Pablo Picasso, âLa femme à la fenêtreâ (1952) © Succession Picasso/DACS, London 2021. Photo: Tate

Pablo Picasso, âLa femme à la fenêtreâ (1952) © Succession Picasso/DACS, London 2021. Photo: Tate

Woman in a Red Hat (c. 1915) : Vanessa Bell

Woman in a Red Hat (c. 1915) : Vanessa Bell

ΧÏονολογοÏμενη ÏεÏίÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïο 1475, Î±Ï Ïή η ÏÏοÏÏÏογÏαÏία ÏÏιÏν ÏεÏάÏÏÏν ÏÎÏει μια Ïαλαιά εÏιγÏαÏή ÏÏο ÏεÏβάζι ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏεικονίζεÏαι ÏÏο κάÏÏ Î¼ÎÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎµÎ¹ÎºÏναÏ, ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿Î´Î®Î³Î·Ïε ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î¹ÏÏοÏικοÏÏ ÏÏο ÏαÏελθÏν να ÏÎ±Ï ÏοÏοιήÏÎ¿Ï Î½ Ïην καθήμενη ÏÏ Smeralda di M. Bandinelli Moglie di VI, ÏÎ¿Ï ÏιÏÏεÏεÏαι ÏÏι είναι η γιαγιά ÏÎ¿Ï Î³Î»ÏÏÏη Baccio Bandinelli. ΩÏÏÏÏο, είναι ÏÎ¹Î¸Î±Î½Ï ÏÏι η εÏιγÏαÏή να ÏÏοÏÏÎθηκε αÏγÏÏεÏα, καθÏÏ Î¿ γλÏÏÏÎ·Ï ÏήÏε Î±Ï ÏÏ Ïο εÏÏÎ½Ï Î¼Î¿ μÏνο Ïο 1530. ÎÏÏ Ïα αÏÏειακά ÏεκμήÏια είναι γνÏÏÏÏ ÏÏι Ïο 1469 η Smeralda ήÏαν ÏÏιάνÏα εÏÏν. ÎÏει ÏÏοÏαθεί ÏÏι η ÏÏοÏÏÏογÏαÏία ζÏγÏαÏίÏÏηκε αÏÏ Îναν αÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î²Î¿Î·Î¸Î¿ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Botticelli καÏά Ïη διάÏκεια ÏÎ·Ï Î´ÎµÎºÎ±ÎµÏÎ¯Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï 1470, ÎµÎ½Ï Î¬Î»Î»Î¿Î¹ ÎµÎ¾Î±ÎºÎ¿Î»Î¿Ï Î¸Î¿Ïν να ÏιÏÏεÏÎ¿Ï Î½ ÏÏι αÏοÏελεί γνήÏιο ÎÏγο ÏÎÏÎ½Î·Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Botticelli. Î ÏÎ¯Î½Î±ÎºÎ±Ï ÎºÎ±ÏαδεικνÏει Ïην μεγάλη ÏÏ Î¼Î²Î¿Î»Î® ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î»Î»Î¹ÏÎÏνη ÏÏην ιÏÏοÏία ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏοÏÏÏογÏαÏίαÏ, αÏομακÏÏνονÏÎ±Ï Ïο ενδιαÏÎÏον αÏÏ Ïα ÏÏαÏικά ÎÏγα εμÏÏοÏÎ¸Î¯Î±Ï ÏÏεÏÏ (ÏÏοÏίλ) και ειÏάγονÏÎ±Ï Ïην ÎµÎ»ÎºÏ ÏÏική ÏÏάÏη ÏÏν ÏÏιÏν ÏεÏάÏÏÏν, εÏιÏÏÎÏονÏÎ±Ï ÎÏÏι ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î¸ÎµÎ±ÏÎÏ Î½Î± αλληλεÏιδÏάÏÎ¿Ï Î½ άμεÏα με Ïα θÎμαÏα ÏÏν ÏινάκÏν. Î Smeralda εμÏανίζεÏαι με Ïο ÏÎÏι ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏο ÏλαίÏιο ÏÎ¿Ï ÏαÏαθÏÏÎ¿Ï , μια άλλη εÏεÏÏεÏη ÏÎ¿Ï Botticelli, αμÏιÏβηÏÏνÏÎ±Ï Î³Î¹Î± άλλη μια ÏοÏά Ïην Îννοια ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏαγμαÏικÏÏηÏÎ±Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ καÏαÏÏίÏÏονÏÎ±Ï Ïο εÏίÏεδο ÏÎ·Ï ÎµÎ¹ÎºÏÎ½Î±Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ Ïον ÏÏÏο μεÏÎ±Î¾Ï Î¸ÎμαÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ θεαÏή. ΥιοθεÏÏνÏÎ±Ï Î±Ï ÏÏ Ïο νÎο ÏÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏοÏÏÏογÏαÏίαÏ, ο Botticelli Îδινε μια αίÏθηÏη κίνηÏÎ·Ï ÏÏÎ¹Ï ÏÏοÏÏÏογÏαÏÎ¯ÎµÏ ÏÎ¿Ï , αÏοδίνονÏÎ±Ï ÏÏοκληÏικά ζÏή ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏίνακÎÏ ÏÎ¿Ï . Îι καινοÏÎ¿Î¼Î¯ÎµÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î»Î»Î¹ÏÎÏνη εÏαναλήÏθηκαν γÏήγοÏα αÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÏ Î³ÏÏÏÎ½Î¿Ï Ï ÏÎ¿Ï . ..

SAINT AVIA (THE JAILED WOMAN)c. 1500 France[1400]

SAINT AVIA (THE JAILED WOMAN)c. 1500 France[1400]

ΣÎÎÎÎΩΣÎÎΣ[10]. https://www.facebook.com/TheMythologi.... MiloÅ¡eviÄ 2021.[1000]. Pierguidi 2002.[1100]. Heckscherthe 1956.[1200]. https://www.facebook.com/permalink.ph.... https://www.samfogg.com/exhibitions/2...

ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎΡÎΦÎÎ

https://www.researchgate.net/publicat..., P. 2021. "The Byzantine Renaissance as the predominant source and impetus for the Italian Renaissance - Theodore Gaza in Mantua, Ferrara, Rome and Naples and Nicolaos Leonicos Tomeos in Venice, Florence and Padua," in Conference: The Byzantine Renaissance as the predominant source and impetus for the Italian Renaissance - Theodore Gaza in Mantua, Ferrara, Rome and Naples and Nicolaos Leonicos Tomeos in Venice, Florence and Padua -At: Laboratório de Estudos Medievais (LEME/UNIFESP) and by the Laboratório de Estudos Mediterrânicos e Bizantinos (LÃMEB), based at the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP), Brazil.

https://ia801200.us.archive.org/1/ite... J. H. Jenkins. 1963. "The Hellenistic Origins of Byzantine Literature," Dumbarton Oaks Papers 17, pp. 37+39-52.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/23206766

Pierguidi, S. 2002. "Botticelli and Protogenes: An anecdote from Pliny's Naturalis Historia," Notes in the History of Art 21 (3), pp. 15-18.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/43872969..., W. S. 1956. "'Anadyomene' in the medieval tradition: (Pelagia - Cleopatra - Aphrodite). A prelude to Botticelli's 'Birth of Venus'," Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek (NKJ) / Netherlands Yearbook for History of Art 7, pp. 1-38.

https://www.ft.com/content/026a19fc-f..., T. 2022. "Why âwoman in the windowâ is such an enduring theme in art," FT Magazine - Visual Arts, <https://www.ft.com/content/026a19fc-f... (14 August 2022).

ÎονιδάÏÎ·Ï Î. 2022. "WOMAN AT THE WINDOW. ÎÎ¥ÎÎÎÎÎ ÎÎΤÎΠΤÎÎ¥ÎΥΣΠÎΠΠΤΠÎÎΩΡÎÎÎ (καÏαÏκοÏία - ÏαÏακÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Ïα)," ÎÎÎÎÎΤÎΣÎ, <https://dnkonidaris.blogspot.com/2022... (14 August 2022).

https://www.academia.edu/48069027/Bot..., A. and C. Elam, eds. 2019. Botticelli Past and Present, UCL Press.

Î ÏÏ

κοÏανÏία ÏοÏ

ÎÏελλή (Botticelli, De calumnia, 1494-1495, ΦλÏÏενÏία, ÎÏ

ÏίÏÏι)

Î ÏÏ

κοÏανÏία ÏοÏ

ÎÏελλή (Botticelli, De calumnia, 1494-1495, ΦλÏÏενÏία, ÎÏ

ÏίÏÏι)Î Îιαβολή (ή ÏÏ ÎºÎ¿ÏανÏία) ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏελλή (ÎÏαλικά: La Calunnia di Apelle, είναι ÏÎ¯Î½Î±ÎºÎ±Ï Î¶ÏγÏαÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïον ÎÏÎ±Î»Ï ÎºÎ±Î»Î»Î¹ÏÎÏνη ÏÎ·Ï ÎναγÎννηÏÎ·Ï Î£Î¬Î½ÏÏο ÎÏοÏιÏÏÎλι. ΦιλοÏεÏνήθηκε ÏεÏίÏÎ¿Ï Ïο 1494 â 1495. ΣήμεÏα βÏίÏκεÏαι ÏÏη ÏÏ Î»Î»Î¿Î³Î® ÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Î¿Ï ÏÎµÎ¯Î¿Ï ÎÏ ÏίÏÏι ÏÏη ΦλÏÏενÏία, ÏÏην Î±Î¯Î¸Î¿Ï Ïα ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ αÏιεÏÏμÎνη ÏÏο μεγάλο Î´Î·Î¼Î¹Î¿Ï ÏγÏ. ΠΣάνÏÏο ÎÏοÏιÏÏÎλι άνÏληÏε Ïο θÎμα ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏÏ Îνα διάÏημο Ïίνακα ÏÎ¿Ï Îλληνα καλλιÏÎÏνη ÏÎ·Ï ÎµÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÏÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÏεÏιÏÎ´Î¿Ï ÎÏελλή, ÏÏÏÏ Î±Ï ÏÏÏ ÏεÏιγÏάÏηκε αÏÏ Ïο ÎÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ¹Î±Î½Ï ÏÏον ÏÎÏαÏÏο ÏÏμο αÏÏ Ïα ογδÏνÏα ÏÏζÏμενα ÎÏγα ÏÎ¿Ï , ÏÏην ÏÏαγμαÏεία ÏÎ¿Ï Î ÎµÏὶ Ïοῦ μὴ ῥᾳδίÏÏ ÏιÏÏεÏειν διαβολá¿.ΠλÏÎ³Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿ ÎÏÎµÎ»Î»Î®Ï ÏιλοÏÎÏνηÏε Ïον Ïίνακα Î±Ï ÏÏ Î®Ïαν ÎÎ½Î±Ï ÏÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Î½Î± ÏεÏιγÏάÏει Ïα ÏÏ Î½Î±Î¹ÏθήμαÏα θλίÏÎ·Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ οÏÎ³Î®Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿ Î¯Î´Î¹Î¿Ï ÎνιÏÏε ÏÏαν καÏηγοÏήθηκε άδικα, αÏÏ Îναν ανÏαγÏνιÏÏή ÏÎ¿Ï , Ïον ÎνÏίÏιλο, για Ïη δήθεν ÏÏ Î¼Î¼ÎµÏοÏή ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏο Îγκλημα ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏ Î½ÏμοÏÎ¯Î±Ï ÎºÎ±Ïά ÏÎ¿Ï Î¦Î±ÏÎ±Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎλληνιÏÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎιγÏÏÏÎ¿Ï , Î ÏÎ¿Î»ÎµÎ¼Î±Î¯Î¿Ï Îâ ÏÎ¿Ï Î£ÏÏήÏα. ÎÏαν αÏοδείÏÏηκε η αθÏÏÏηÏά ÏÎ¿Ï , αÏοÏάÏιÏε να μεÏαÏÎÏει Ïο ÏÏοÏÏÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î²Î¯Ïμα ÏÏον Ïίνακα Î±Ï ÏÏ. Το ÎÏγο δεν ÏÏζÏÏαν ÏÏÎ¹Ï Î¼ÎÏÎµÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏοÏιÏÏÎλι. ΩÏÏÏÏο η ÏεÏιγÏαÏή ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ¹Î±Î½Î¿Ï ÎµÎ¯Ïε μεÏαÏÏαÏÏεί ÎµÏ ÏÎÏÏ. ΣÏον Î´Î¹ÎºÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ïίνακα, ο αναγεννηÏιακÏÏ Î¶ÏγÏάÏÎ¿Ï Î´Î¹Î±ÏήÏηÏε Ïο ÏÎºÎ·Î½Î¹ÎºÏ ÏÏήÏιμο ÏÏν μοÏÏÏν αÏÏ Ïην ÏεÏιγÏαÏή ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ¹Î±Î½Î¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ δημιοÏÏγηÏε Îνα ÏεÏίÏεÏνα ÏÏολιÏμÎνο αÏÏιÏεκÏÎ¿Î½Î¹ÎºÏ ÏÏνÏο για εκείνεÏ.

ÎÎ Î ÎÎΣΩ ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎΡÎ[10]: ÎÏμα ÏÏ ÎºÎ¿ÏανÏÎ¯Î±Ï Ï ÏήÏξε κάÏοÏε και ο ÏεÏίÏÎ·Î¼Î¿Ï Î¶ÏγÏάÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎλληνιÏÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÏεÏιÏÎ´Î¿Ï ÎÏελλήÏ, ο οÏÎ¿Î¯Î¿Ï ÎºÎ±ÏηγοÏήθηκε αÏÏ ÎºÎ¬Ïοιον ομÏÏεÏÎ½Ï ÏÎ¿Ï , Ïον ÎνÏίÏιλο, ÏÏÏ ÏÏ Î½ÏμÏÏηÏε ÏÏο ÏÎ»ÎµÏ ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î¥ÏάÏÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï Î¤ÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎεοδÏÏα ενανÏίον ÏÎ¿Ï Î²Î±Ïιλιά ÏÎ·Ï ÎιγÏÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÎµÏ ÎµÏγÎÏη ÏÎ¿Ï , Î ÏÎ¿Î»ÎµÎ¼Î±Î¯Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ. Î ÏεÏιÏÎÏεια ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏελλή Îληξε γÏήγοÏα καθÏÏ Î±ÏοδείÏθηκε ÏÏÏ Î´ÎµÎ½ είÏε εÏιÏκεÏÏεί ÏοÏÎ ÏÎ¿Ï Ïην ΤÏÏο. ÎÏÎ ÏÏι ÏαίνεÏαι ÏμÏÏ Ïον ÏÏιγμάÏιÏε ÏÏÏο ÏÎ¿Ï Î¸ÎληÏε να αÏοÏÏ ÏÏÏει Ïην οδÏνη ÏÎ¿Ï Î¶ÏγÏαÏίζονÏÎ±Ï Îνα ÏÎ¿Î»Ï ÏÏνθεÏο ÎÏγο με ÏίÏλο «Îιαβολή». Î ÏÎ¯Î½Î±ÎºÎ±Ï Î´Ï ÏÏÏ ÏÏÏ Î´Îµ διαÏÏθηκε. ÎιÏÎ½ÎµÏ Î±ÏγÏÏεÏα ÏμÏÏ Î¿ ΣάνÏÏο ÎÏοÏιÏÏÎλλι εμÏÎ½ÎµÏ ÏμÎÎ½Î¿Ï Î±ÏÏ ÏÎ¹Ï Î»ÎµÏÏομεÏÎµÎ¯Ï ÏεÏιγÏαÏÎÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏÎ³Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏελλή ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿ ÎÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ¹Î±Î½ÏÏ Î±Î½ÎÏεÏε ÏÏην ÏÏαγμαÏεία ÏÎ¿Ï , «ΠεÏὶ Ïοῦ μὴ ῥᾳδίÏÏ ÏιÏÏεÏειν διαβολá¿Â», καÏάÏεÏε να Ïον αναÏαÏαγάγει και να αÏοδÏÏει με μεγάλη ÏαÏαÏÏαÏικÏÏηÏα Ïο δÏάμα ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏÏÎ±Î¯Î¿Ï Î¶ÏγÏάÏÎ¿Ï Î¼ÎµÏαÏÎÏονÏÎ¬Ï Ïο ÏÏην εÏοÏή ÏÎ¿Ï .

O ÎÎΣΣÎÎÎÎÎÎÎΥΣ ÎÎÎÎ. ÎÎÎÎΣ ΣΤÎÎ 'ÎÎΤΡÎÎΠΤΩΠÎÎÎΩÎ' ΤÎÎ¥ ÎÎ ÎΤÎΤΣÎÎÎÎ (Sandro Botticelli, âAdoration of the Magiâ, 1475-1476. Uffizi, Italy)

ÎκÏιβÏÏ Î±ÏιÏÏεÏά ÏÎ¿Ï ÎεοδÏÏÎ¿Ï Îαζή [Î Î. ÎαζήÏ, ο εÏονομαζÏÎ¼ÎµÎ½Î¿Ï ÎεÏÏαλονικεÏÏ Î® Thessalonicensis ÏÏα λαÏινικά, ήÏαν ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î±Ï Î¿Ï Î¼Î±Î½Î¹ÏÏήÏ, μεÏαÏÏαÏÏÎ®Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏιÏÏοÏÎÎ»Î¿Ï Ï, εÏιÏÏÎ®Î¼Î¿Î½Î±Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ λÏÎ³Î¹Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï 15Î¿Ï Î±Î¹ÏνοÏ, διακÏίθηκε ÏÏην λεγομÎνη Î ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎÎÎÎÎ ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎÎΣÎ!] ÏÏÎκεÏαι ο ÏοÏηγÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ïίνακα, Lorenzo Medici, ÏÏα μαÏÏα και δεξιά ο Î¯Î´Î¹Î¿Ï Î¿ ζÏγÏάÏÎ¿Ï Sandro Botticelli με ÏοÏÏοκαλί μανδÏα. ÎÎ½Ï Î¿ Î³Î¹Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î Î¹ÎÏÏο ÏÏ Î´ÎµÏÏεÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ¬Î³Î¿Ï Î³Î¿Î½Î±Ïίζει ÏÏο κÎνÏÏο ÏÎ·Ï ÎµÎ¹ÎºÏÎ½Î±Ï Î¼Îµ κÏκκινο μανδÏα, δίÏλα ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ ο αδεÏÏÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î¤Î¶Î¹Î¿Î²Î¬Î½Î¹ ÏÏ ÏÏίÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ¬Î³Î¿Ï ÎµÎ½Ï Î±ÏεικονίζονÏαι και Ïα εγγÏνια ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏζιμο, Î¤Î¶Î¿Ï Î»Î¹Î¬Î½Î¿ και ÎοÏÎνÏζο. Îι ÏÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÎÎδικοι ÏÎ¿Ï ÏαÏÎ¿Ï Ïίαζαν ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÎÎ¬Î³Î¿Ï Ï ÎµÎ¯Ïαν ήδη Ïεθάνει Ïην ÏÏιγμή ÏÎ·Ï Î´Î·Î¼Î¹Î¿Ï ÏÎ³Î¯Î±Ï Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Ïίνακα και η ΦλÏÏενÏία ÎµÎºÏ Î²ÎµÏνάÏο αÏÏ Ïον ÎοÏÎνÏζο, ÏÏοÏανÏÏ Î¼ÎµÎ³Î¬Î»Î¿ Î¸Î±Ï Î¼Î±ÏÏή ÏÎ¿Ï Îαζή, ÏÎ¿Ï Î²ÏιÏκÏÏαν ακÏιβÏÏ ÏίÏÏ Î±ÏÏ Ïην ÏλάÏη ÏÎ¿Ï .-------------------------------------------------------------------Immediately to the left of Theodor Gaza stands the client of the painting, Lorenzo Medici, in black, and to the right is the painter Sandro Botticelli himself, in an orange cloak. While his son Piettro as the second Magi kneels in the center of the picture in a red cloak, next to him are his brother Giovanni as the third Magi and Cosimo's grandchildren Giuliano and Lorenzo pictured. Three Mediciâs presenting three Magiâs had already died at the time of creation of this painting, and Florence was ruled by Lorenzo, obviously very fond of Gaza, located just behind his back.

.. From 1440 to 1449, as the successor of the Byzantine Nicholas Secundinus, Gaza taught Greek while studying at Ferrara. His service in that city was the first sign of the dispersal of Greek learning in the European West, as it took place only a few decades after Chrysoloras' first systematic lectures on the Greek language in the Renaissance at a Florentine Studium. Gaza's lectures were so successful that in1449 he was appointed the first rector of the University of Ferrara after its renewal by Duke Lionello d'Este.Gaza's surviving inaugural speech, âOn Greek Writersâ (âDe litteris graecisâ), is probably the earliest surviving inaugural presentation on the importance of Greek studies held in Italy by an emigrant Byzantine scholar. Manuel Chrysoloras' earlier presentation in Florence has not been preserved. In hispresentation, Gaza emphasized that the ancient Romans also had extensive knowledge of Greek literature and its invaluable value for active participation in political life. According to Gaza, leading Roman political figures sent their sons to study in Greece. SOURCE: The Byzantine Renaissance as the predominant source and impetus for the Italian Renaissance - Theodore Gaza in Mantua, Ferrara, Rome and Naples and Nicolaos Leonicos Tomeos in Venice, Florence and Padua - <https://www.researchgate.net/.../3516... ΠΣΧÎÎΠΤΩΠÎÎÎÎΩΠ- ΡÎΦÎÎÎ -->

Î ÎÏ Î¶Î±Î½Ïινή [ΠαλαιολÏγεια] ÎναγÎννηÏη ÏÏ Î· ÎºÏ ÏίαÏÏη Ïηγή και ÏθηÏη για Ïην ÎÏαλική ÎναγÎννηÏη[20]

«ΠÎÏ Î¶Î±Î½Ïινή ÎναγÎννηÏη ÏÏ Ïο κοÏÏ Ïαίο θεμÎλιο ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏÎ±Î»Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎναγÎννηÏηÏ: ÎεÏδÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ±Î¶Î®Ï ÏÏην ÎάνÏοβα, ΦεÏάÏα, ΡÏμη και ÎάÏολη και ÎικÏÎ»Î±Î¿Ï ÎεÏÎ½Î¹ÎºÎ¿Ï ÎÏμεÏÏ ÏÏην ÎενεÏία, ΦλÏÏενÏία και ΠάνÏοβα" ÎÏο ακÏμη άÏομα ÏÏν οÏοίÏν η άÏιξη ÏÏην ÎÏαλία βοήθηÏε ÏάÏα ÏÎ¿Î»Ï Î½Î± καÏÎµÏ Î¸Ïνει Ïον Ï ÏάÏÏονÏα ÎνθÏÏÏιÏÎ¼Ï Î±ÏÏ Î±Ï Ïήν Ïην αÏÏική ÎμÏαÏη ÏÎ¿Ï ÏηÏοÏÎ¹ÎºÎ¿Ï Ï ÏήÏξαν οι Î²Ï Î¶Î±Î½Ïινοί καθηγηÏÎÏ ÎεÏδÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ±Î¶Î®Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÎικÏÎ»Î±Î¿Ï ÎεÏÎ½Î¹ÎºÎ¿Ï ÎÏμεÏÏ, ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ οι δÏο ÏÏοήδÏÎµÏ Ïαν εδÏÏν αÏιεÏÏμÎνÏν ÏÏην ελληνική ÏιλοÏοÏία Ïε ÏανεÏιÏÏήμια ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏÎ±Î»Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï Î§ÎµÏÏονήÏÎ¿Ï . ΠκαÏιÎÏα ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î¼ÏοÏεί να είναι διÏαÏμÎνη Ïε διαÏοÏεÏικÎÏ Î¼ÎµÎ³Î¬Î»ÎµÏ ÏάÏειÏ. ÎÏιÏμÎνα ÏÏάδια είναι ανεÏαÏκÏÏ Î³Î½ÏÏÏά λÏÎ³Ï ÎµÎ»Î»ÎµÎ¯ÏεÏÏ ÏÏÏÏν ÏÏιν αÏÏ Ïην ÏÏÏÏη ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏνÏÏανÏÎ¹Î½Î¿Ï ÏÏλεÏÏ ÏÏα ÏÎ¿Ï Ïκικά ÏÎÏια Ïο 1453. Îλλα, αÏκεÏά μεγαλÏÏεÏÎ·Ï Î´Î¹Î¬ÏÎºÎµÎ¹Î±Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ Ïιο ÏημανÏικά για Ïην ιÏαλική ÎναγÎννηÏη, ÏαÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¹Î¬Î¶Î¿Ï Î½ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î²Ï Î¶Î±Î½ÏινοÏÏ Î»ÏÎ³Î¹Î¿Ï Ï ÏÏ Î»ÎκÏοÏÎµÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏαÏÏολοÏνÏαι Ïε Ïλην Ïην ÎÏαλία, Ïην εÏοÏή ÏÎ¿Ï Î±Ï Ïή η ÏÏÏα Îμελλε να ÏÏάÏει ÏÏο αÏÏγειο ÏÎ·Ï ÏÎ®Î¼Î·Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏ Ïο κÎνÏÏο ÏÎ¿Ï ÎνθÏÏÏιÏμοÏ.Π«ÎνθÏÏÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎναγεννήÏεÏÏ», ÎÎ½Î±Ï Î¬Î½Î¸ÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Îµ ÎµÏ ÏÏ Ïεδίο ÏκÎÏεÏν και ÏÏάξεÏν, ÎÎ½Î±Ï ÏαγκοÏÎ¼Î¯Î¿Ï ÏÎ®Î¼Î·Ï ÏÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏ Î½Î®Î¸ÏÏ ÎµÏαÏμÏζεÏαι ÏÏον ιÏÎ±Î»Î¹ÎºÏ Î¿Ï Î¼Î±Î½Î¹ÏÎ¼Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ Ïην αναγÎννηÏη, ÏÏοÏανÏÏ Î±Î½Î®ÎºÎµÎ¹ ÏÏÏÏα και κÏÏια ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î²Ï Î¶Î±Î½ÏινοÏÏ Î¼ÎµÎ»ÎµÏηÏÎÏ.ÎÏÏÏ ÏαίνεÏαι ξεκάθαÏα εδÏ, η Ïίζα ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÎ·Ï Î¿Ï ÏÎ¯Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Â«ÎνθÏÏÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎναγεννήÏεÏÏ» ÎγκειÏαι ÏÏην ÏÏαγμαÏικÏÏηÏα ÏÏην Îλληνική και ÎÏ Î¶Î±Î½Ïινή «εγκÏκλειο Ïαιδεία», ÏÏÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ Ïην «ÏÎ¿Î»Ï Î¸ÎµÎ¼Î±Ïική θεÏÏηÏη», κÏÏια ÏαÏακÏηÏιÏÏικά ενÏÏ ÎµÎºÏÎ±Î¹Î´ÎµÏ ÏÎ¹ÎºÎ¿Ï ÏÏ ÏÏήμαÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï Î±Ï ÏοκÏαÏοÏÎ¯Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÏÏοÏοÏοÏÏε Ïε ÏÎ»Î¿Ï Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÎºÎ»Î¬Î´Î¿Ï Ï ÏÏην ανεÏÏÏ Î³Î¼Îνη ÎÏ ÏÏÏη και Ïην ÎεÏÏγειο για ÏεÏιÏÏÏÏεÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î±ÏÏ Îνδεκα αιÏνεÏ, καÏά Ïον ίδιο ÏÏÏÏο ÏÎ¿Ï Ïο ΠανεÏιÏÏήμιο ÏÎ·Ï ÎαγναÏÏÎ±Ï Î® ΠανδιδακÏήÏιο ή ÎÎ±Î¸Î¿Î»Î¹ÎºÏ Î Î±Î½/μιο ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏνÏÏανÏÎ¹Î½Î¿Ï ÏÏλεÏÏ, η ÎδÏα ÏÎ·Ï Î¿ÏÎ¿Î¯Î±Ï ÎµÏÏημαÏοδοÏείÏο αÏÏ Ïον ΣÎÏβο ΤÏάÏο ÎÏÏÎ¿Ï Ïον ÎδÏναμο (!?)[ΠΣÏÎÏÎ±Î½Î¿Ï ÎÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ ÎÏοÏÏαν, γνÏÏÏÏÏ ÏÏ ÎÏοÏÏαν ο ÎÏÏÏ ÏÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÏα ελληνικά ÏÏ Î£ÏÎÏÎ±Î½Î¿Ï ÎÎ¿Ï Ïάν, ήÏαν βαÏÎ¹Î»Î¹Î¬Ï ÏÎ·Ï Î£ÎµÏÎ²Î¯Î±Ï Î±ÏÏ ÏÎ¹Ï 8 ΣεÏÏεμβÏÎ¯Î¿Ï 1331 και ÎÏ ÏοκÏάÏοÏÎ±Ï Î£ÎÏβÏν, ÎλλήνÏν, ÎÎ¿Ï Î»Î³Î¬ÏÏν, ÎλάÏÏν και ÎλβανÏν αÏÏ ÏÎ¹Ï 16 ÎÏÏÎ¹Î»Î¯Î¿Ï 1346 μÎÏÏι Ïον θάναÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ], ήÏαν Ïο κοÏÏ Ïαίο ίδÏÏ Î¼Î± για ÏÏεδÏν μια ÏιλιεÏία ÏÏιν αÏÏ Ïην ίδÏÏ Ïη ÏÏν ÏανεÏιÏÏημίÏν ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏολÏνια, ÏÎ·Ï Î Î¬Î½ÏοβαÏ, ÏÎ·Ï Î£Î¿ÏβÏÎ½Î½Î·Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÎ·Ï ÎξÏÏÏδηÏ.ÎÏÏ ÎµÎºÎµÎ¯ ακÏιβÏÏ ÏÏοÎÏÏεÏαι η ιÏαλική ÎναγÎννηÏη. ------------------------------------------------------------------- The Byzantine Renaissance as the predominant source and impetus for the Italian Renaissance âThe Byzantine Renaissance as the premier foundation of the Italian Renaissance: Theodore Gaza in Mantova, Ferrara, Rome and Naples and Nikolaos Leonikostomeos in Venice, Florence and Paduaâ Two more persons whose arrival in Italy helped immensely to direct the existing Humanism from its original rhetorician emphasis were Byzantine professors Theodoros Gaza and Niccolo Leonico Tomeo, who both chaired a Greek philosophy at universities around the peninsula. Their careers may be divided into different large phases. Certain stages are insufficiently known due to a lack of resources before thefall of the Byzantine capital Constantinople into Turkish hands in 1453. Other, considerably longer and more important for the Italian Renaissance, represents Byzantine scholars as lecturers employed throughout Italy, at the time when this country was about to reach the height of its fame as a Humanism center.The âRenaissance Manâ, a man with broad scopes of thoughts and deeds, a world-renowned term usually applied to Italian Humanism and Renaissance, obviously belongs first and foremost to Byzantine scholars.As clearly visible here, the root of the term and essence of a âRenaissance Manâ actually is in Greek and Byzantine âenkyklios paideiaâ, as âall embracing thoughtfulnessâ, main characteristics of an educational system of the empire that was leading in all terms and most developed in Europe and the Mediterranean for more than eleven centuries, in as much as Constantinopleâs Catholicon University, the headquarters of which were financed by Serbian Tsar UroÅ¡ the Weak (!?), was the leading one for nearly a millennium before Bologna, Padua, Sorbonne and Oxford universities were established.That is exactly where an Italian Renaissance is coming from. Predrag MiloÅ¡eviÄ -->

ΠΠΡΩΤÎÎÎÎÎΣ ÎΩÎΡÎΦÎÎΩΠΤÎÎ ÎÎÎΥΣΠ(ÎΡÎΠΤÎÎ¥ Giorgio Vasari, 1540s. Vasari's House, Arezzo)[1000]

ΠζÏγÏάÏÎ¿Ï Î ÏÏÏογÎÎ½Î·Ï Î®Ïαν διάÏÎ·Î¼Î¿Ï Î³Î¹Î± Îναν Ïίνακα ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏεικÏνιζε Ïον ήÏÏα ÎÎ¬Î»Ï Ïο ÏÏην ΡÏδο, για Ïην ολοκλήÏÏÏη ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿ÏÎ¿Î¯Î¿Ï ÎµÏγάÏÏηκε εÏÏά ÏÏÏνια. ÎÏαν μάλιÏÏα ο ÏÎ¯Î½Î±ÎºÎ±Ï Î²ÏιÏκÏÏαν ÏÏο ÏÎµÎ»Î¹ÎºÏ ÏÏάδιο, Ïο 305-304 Ï.Χ., ο ÎημήÏÏÎ¹Î¿Ï Î Î¿Î»Î¹Î¿ÏκηÏÎ®Ï ÎµÎ¾ÎµÏÏÏάÏÎµÏ Ïε ενανÏίον ÏÎ·Ï Î¡ÏÎ´Î¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹, αÏÏ ÏεβαÏÎ¼Ï ÏÏÎ¿Ï Îνα ÏÏÏο εξαιÏεÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÎÏγο ÏÎÏνηÏ, διÎÏαξε Ïα ÏÏÏαÏεÏμαÏά ÏÎ¿Ï Î½Î± μην ÏÏ ÏÏολήÏÎ¿Ï Î½ Ïην ÏÏλη. ÎαÏά Ïη διάÏκεια ÏÎ·Ï ÏολιοÏκίαÏ, ο καλλιÏÎÏÎ½Î·Ï ÏÏ Î½ÎÏιÏε να εÏγάζεÏαι αμÎÏιμνοÏ, λÎγονÏÎ±Ï ÏαÏακÏηÏιÏÏικά ÏÏι ο βαÏÎ¹Î»Î¹Î¬Ï Îκανε ÏÏλεμο ενανÏίον ÏÎ·Ï Î¡ÏÎ´Î¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÏι ενανÏίον ÏÏν ÏεÏνÏν. Î ÎημήÏÏÎ¹Î¿Ï ÎθεÏε Ï ÏÏ ÏÏοÏÏηÏη Ïον Î ÏÏÏογÎνη, για να διαÏÏαλίÏει Ïη ÏÏμαÏική ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÎºÎµÏαιÏÏηÏα. Î¥ÏÏ Î±Ï ÏÎÏ ÏÎ¹Ï ÏÏ Î½Î¸Î®ÎºÎµÏ Î¿ καλλιÏÎÏÎ½Î·Ï Î¶ÏγÏάÏιÏε Ïον ÏεÏίÏημο ÎναÏÎ±Ï Ïμενο ΣάÏÏ ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï . ................. ..................................................................................................... ΣÏο ÎÏγο Î¦Ï Ïική ÎÏÏοÏία (Naturalis Historia) ÏÎ¿Ï Î Î»Î¹Î½Î¯Î¿Ï , ο Î ÏÏÏογÎÎ½Î·Ï Î±Î½Î±ÏÎÏεÏαι ÏÏ Î¿ Ïιο διάÏÎ·Î¼Î¿Ï Î¶ÏγÏάÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏεÏάÏÏÎ¿Ï Î±Î¹Ïνα Ï.Χ. μαζί με Ïον ÎÏελλή, ÏεÏιγÏάÏεÏαι δε ÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î»Î»Î¹ÏÎÏÎ½Î·Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î´Î¯Î½ÎµÎ¹ ιδιαίÏεÏη ÏÏοÏοÏή ÏÏην λεÏÏομÎÏεια. ΣÏμÏÏνα με Ïον Πλίνιο, ÏÏαν ο Î ÏÏÏογÎÎ½Î·Ï Î¶ÏγÏάÏιζε Ïο Ïιο διάÏημο ÎÏγο ÏÎ¿Ï - ο ÎºÏ Î½Î·Î³ÏÏ ÎÎ±Î»Ï ÏÏÏ ÏÏ Î½Î¿Î´ÎµÏ ÏÎ¼ÎµÎ½Î¿Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïον ÏκÏλο ÏÎ¿Ï - δοÏλεÏε αÏÏαμάÏηÏα Ïε μία λεÏÏομÎÏεια, ÏάÏνονÏÎ±Ï Îναν ÏÏÏÏο αÏεικονίÏεÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏÏÎ¿Ï Î³ÏÏÏ Î±ÏÏ Ïο ÏÏÏμα ÏÎ¿Ï ÏκÏÎ»Î¿Ï , ÎÏÏ ÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ¾Î¿ÏγίÏÏηκε και ÎÏιξε Îνα ÏÏÎ¿Ï Î³Î³Î¬Ïι ÏÏην εικÏνα. ÎÏ ÏÏ Î¬ÏηÏε ÏÏι ο Botticelli ίÏÏÏ Î¸Î± είÏε οÏίÏει ÏÏ 'Îνα ίÏνοÏ', ÏÏο οÏοίο ο Î ÏÏÏογÎÎ½Î·Ï Î±Î½Î±Î³Î½ÏÏιÏε ÏÏι εÏιÏÏ Î³ÏάνεÏο ÏÏ Ïαία Ïο αÏοÏÎλεÏμα για Ïο οÏοίο είÏε ÏÏοÏÏαθήÏει ÏÏÏο κοÏιαÏÏικά. ÎÏ ÏÏ Ïο εÏειÏÏδιο, μαζί με άλλα ανÎκδοÏα ÏÎ¿Ï Î Î»Î¹Î½Î¯Î¿Ï Î³Î¹Î± ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î¼ÎµÎ³Î¬Î»Î¿Ï Ï Î¶ÏγÏάÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÎ·Ï Î±ÏÏαιÏÏηÏαÏ, αÏεικονίζεÏαι Ïε μια ÏοιÏογÏαÏία ζÏγÏαÏιÏμÎνη αÏÏ Ïον Vasari ÏÏην οικία ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏο ÎÏÎÏÏο. ........ "ÎιαÏί αÏλÏÏ ÏίÏνονÏÎ±Ï Îνα ÏÏÎ¿Ï Î³Î³Î¬Ïι γεμάÏο με διαÏοÏεÏικά ÏÏÏμαÏα ÏÏον ÏοίÏο, Î´Î·Î¼Î¹Î¿Ï ÏγείÏε ÎνανλεκÎ, ÏÏον οÏοίο μÏοÏείÏε να δείÏε μια ÏμοÏÏη αÏεικÏνιÏη ÏοÏÎ¯Î¿Ï .' ΦαίνεÏαι ÏÏι με Î±Ï ÏÎÏ ÏÎ¹Ï Î»ÎξειÏ, ÏÎ¹Ï Î¿ÏÎ¿Î¯ÎµÏ ÏαÏαθÎÏει με εÏιμÎλεια ο ÎεονάÏνÏο ÏÏο Libro di Pittura, ο Botticelli δικαιολογεί Ïην αδιαÏοÏία ÏÎ¿Ï Î³Î¹Î± Ïην ζÏγÏαÏική ÏοÏÎ¯Î¿Ï . Το ÏÏÏÏÏÏÏ Ïο κείμενο ÏÎ¿Ï da Vinci ÎÏει ÎÏει Ïαθεί, αλλά ο κÏÎ´Î¹ÎºÎ±Ï ÏÏην ÎÏοÏÏολική Îιβλιοθήκη ÏÎ¿Ï ÎαÏÎ¹ÎºÎ±Î½Î¿Ï ÏÏην οÏοία Ïο αÏÏÏÏαÏμα ÎÏει αναÏαÏαÏθεί θεÏÏείÏαι ÏÎ¿Î»Ï Î±Î¾Î¹ÏÏιÏÏη. Î Î±Ï 'Ïλα Î±Ï Ïά, ο Horne εξÎÏÏαÏε αμÏιβολία ÏÏ ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ïην ειλικÏίνεια ÏÎ·Ï Î´Î·Î»ÏÏεÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏοÏιÏÏÎλι, ÏÎ¿Ï , καÏά Ïη γνÏμη ÏÎ¿Ï , δεν μÏοÏοÏÏε να διαβαÏÏεί με οÏοιονδήÏοÏε άλλο ÏÏÏÏο εκÏÏÏ Î±ÏÏ "ÏαÏάδοξο ÏÏÏ Î»" ÏαÏακÏηÏιÏÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î»Î»Î¹ÏÎÏνη ÏÎ·Ï Î¦Î»ÏÏενÏίαÏ. ΣÏην ÏÏαγμαÏικÏÏηÏα, είναι αÏίθανο ÏÏι ο ÎÏοÏιÏÏÎλι θα μÏοÏοÏÏε ÏοβαÏά να ÏÏολιάÏει Ïην ζÏγÏαÏική ÏοÏÎ¯Î¿Ï Î¼Îµ Î±Ï ÏοÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ αν ÏÏηÏιμοÏοιοÏÏε Ïην ακÏαία εικÏνα ÏÎ¿Ï Î»ÎµÎºÎ ÏÏον ÏοίÏο ÏÏ Ï ÏοκαÏάÏÏαÏο ÏÎ¿Ï 'ÏμοÏÏÎ¿Ï ÏοÏÎ¯Î¿Ï ' θα ήÏαν μÏνο Ïε ÏÏÎÏη με Ïο ανÎκδοÏο ÏÎ¿Ï Î Î»Î¹Î½Î¯Î¿Ï Î³Î¹Î± Îναν αÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Ïιο διάÏÎ·Î¼Î¿Ï Ï Î¶ÏγÏάÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÎ·Ï Î±ÏÏαιÏÏηÏαÏ, Ïον Î ÏÏÏογÎνη ...

ÎÎ½Î±Î´Ï Î¿Î¼Îνη ÎÏÏοδίÏη & Botticelli[1100]

MFA AC. NR. 1982.286, ÏÏ

ÏÏεÏιÏθείÏα με Ïην ÎλεοÏάÏÏα η οÏοία αναδÏ

ομÎνη ÏÏ

νανÏά Ïον ÎνÏÏνιο, Ïην ÎÏία Πελαγία - ÎαÏγαÏίÏα ÎºÎ»Ï (γενειοÏÏÏο ή μή)

MFA AC. NR. 1982.286, ÏÏ

ÏÏεÏιÏθείÏα με Ïην ÎλεοÏάÏÏα η οÏοία αναδÏ

ομÎνη ÏÏ

νανÏά Ïον ÎνÏÏνιο, Ïην ÎÏία Πελαγία - ÎαÏγαÏίÏα ÎºÎ»Ï (γενειοÏÏÏο ή μή) ÎναδÏ

ομÎνη ÏοÏ

ÎεοÏίλοÏ

ÎναδÏ

ομÎνη ÏοÏ

ÎεοÏίλοÏ

Î ÏοÏÏÏογÏαÏία νεÏÎ±Ï Î³Ï Î½Î±Î¯ÎºÎ±Ï[1200]Portrait of a Young Woman is a painting which is commonly believed to be by the Italian Renaissance painter Sandro Botticelli, executed between 1480 and 1485. The woman is shown in profile but with her bust reveal a cameo medallion she is wearing around her neck. The medallion is a copy in reverse of "Nero's Seal" (**), a famous antique carnelian representing Apollo and Marsyas, which belonged to Lorenzo de' Medici . The art historian Aby Warburg first suggested the painting was an idealised portrait of Simonetta Vespucci. This challenged a previous interpretation, put forward by German scholars, according to which the painting describes an ideally beautiful young woman mythologised as a nymph or goddess, a view reflected in the title given it by the Städel. It belongs to a group of such paintings by Botticelli or his workshop. Art historian Emanuele Lugli has suggested that the three "tassels" of hair at the center of the painting represents downward flames, symbolising the love that onlookers ought to experience when looking at the portrait since, in the Renaissance it was thought that "hair inflames desire.

(**)In the story about Apollo and Marsyas, a Phrygian mortal named Marsyas, who may have been a satyr, ( satyrs are one of a class of lustful, drunken woodland gods. In Greek art they were represented as a man with a horse's ears and tail, but in Roman representations as a man with a goat's ears, tail, legs, and horns.) who boasted about his musical skill on the aulos. The aulos was a double-reed flute. The instrument has multiple origin stories. In one, Marsyas found the instrument after Athena had abandoned it. In another origin story, Marsyas invented the aulos. Cleopatra's father evidently also played this instrument, since he was known as Ptolemy Auletes. Marsyas claimed he could produce music on his pipes far superior to that of the cithara-plucking Apollo. Some versions of this myth say it was Athena who punished Marsyas for daring to pick up the instrument she had discarded (because it had disfigured her face when she puffed out her cheeks to blow). In response to the mortal braggadocio, different versions hold that either the god challenged Marsyas to a contest or Marsyas challenged the god. The loser would have to pay a gruesome price. In their music contest, Apollo and Marsyas took turns on their instruments: Apollo on his stringed cithara and Marsyas on his double-pipe aulos. Although Apollo is the god of music, he faced a worthy opponent: musically speaking, that is. Were Marsyas truly an opponent worthy of a god, there would be little more to be said. The deciding judges are also different in different versions of the story. One holds that the Muses judged the wind vs. string contest and another version says it was Midas, king of Phrygia. Marsyas and Apollo were almost equal for the first round, and so the Muses judged Marsyas the victor, but Apollo had not yet given up. Depending on the variation you are reading, either Apollo turned his instrument upside down to play the same tune, or he sang to the accompaniment of his lyre. Since Marsyas could neither blow into the wrong and widely separate ends of his aulos, nor singâeven assuming his voice could have been a match for that of the god of musicâwhile blowing into his pipes, he did not stand a chance in either version. Apollo won and claimed the prize of the victor that they had agreed upon before beginning the contest. Apollo could do whatever he wished to Marsyas. So Marsyas paid for his hubris by being pinned to a tree and flayed alive by Apollo.The short story is ; `Nero`s seal` was a hidden message given by Botticelli ; `do not challenge god` Sandro Botticelli was fundamentalist religious man of early Renausans .

'ÎÎ¥ÎÎÎÎÎΣ ΣΤΠΠÎΡÎÎΥΡÎ': ÎΠΠΤÎÎ ÎÎÎΩÎΤΠ& ÎÎ¥ÎÎÎÎÎΠΤÎÎΧÎÎΡÎΦΠΣΤÎÎ ÎÎ ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎÎΥΨΠΤÎΣ ÎÎÎÎÎΤÎÎÎÎΣ ÎΠΠΤÎÎ BOTICELLI .. ÎΤÎÎ Î ÎÎ¥ÎÎÎÎÎ Î ÎΡÎÎÎÎ ÎÎ ÎÎΡΡÎΣ ΤΠ'ÎΡÎÎ'![1300]

âWomen in a loggiaâ from ramp house deposit, Mycenae 'ÎÏ

Î½Î±Î¯ÎºÎµÏ ÏÏο θεÏÏείο' ÎÏ

κήναι

âWomen in a loggiaâ from ramp house deposit, Mycenae 'ÎÏ

Î½Î±Î¯ÎºÎµÏ ÏÏο θεÏÏείο' ÎÏ

κήναι Botticelliâs Portrait of Smeralda Bandinelli, c147l, âbreaking the frameâ.

Botticelliâs Portrait of Smeralda Bandinelli, c147l, âbreaking the frameâ.

Pablo Picasso, âLa femme à la fenêtreâ (1952) © Succession Picasso/DACS, London 2021. Photo: Tate

Pablo Picasso, âLa femme à la fenêtreâ (1952) © Succession Picasso/DACS, London 2021. Photo: Tate Woman in a Red Hat (c. 1915) : Vanessa Bell

Woman in a Red Hat (c. 1915) : Vanessa BellΧÏονολογοÏμενη ÏεÏίÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïο 1475, Î±Ï Ïή η ÏÏοÏÏÏογÏαÏία ÏÏιÏν ÏεÏάÏÏÏν ÏÎÏει μια Ïαλαιά εÏιγÏαÏή ÏÏο ÏεÏβάζι ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏεικονίζεÏαι ÏÏο κάÏÏ Î¼ÎÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎµÎ¹ÎºÏναÏ, ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿Î´Î®Î³Î·Ïε ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î¹ÏÏοÏικοÏÏ ÏÏο ÏαÏελθÏν να ÏÎ±Ï ÏοÏοιήÏÎ¿Ï Î½ Ïην καθήμενη ÏÏ Smeralda di M. Bandinelli Moglie di VI, ÏÎ¿Ï ÏιÏÏεÏεÏαι ÏÏι είναι η γιαγιά ÏÎ¿Ï Î³Î»ÏÏÏη Baccio Bandinelli. ΩÏÏÏÏο, είναι ÏÎ¹Î¸Î±Î½Ï ÏÏι η εÏιγÏαÏή να ÏÏοÏÏÎθηκε αÏγÏÏεÏα, καθÏÏ Î¿ γλÏÏÏÎ·Ï ÏήÏε Î±Ï ÏÏ Ïο εÏÏÎ½Ï Î¼Î¿ μÏνο Ïο 1530. ÎÏÏ Ïα αÏÏειακά ÏεκμήÏια είναι γνÏÏÏÏ ÏÏι Ïο 1469 η Smeralda ήÏαν ÏÏιάνÏα εÏÏν. ÎÏει ÏÏοÏαθεί ÏÏι η ÏÏοÏÏÏογÏαÏία ζÏγÏαÏίÏÏηκε αÏÏ Îναν αÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î²Î¿Î·Î¸Î¿ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Botticelli καÏά Ïη διάÏκεια ÏÎ·Ï Î´ÎµÎºÎ±ÎµÏÎ¯Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï 1470, ÎµÎ½Ï Î¬Î»Î»Î¿Î¹ ÎµÎ¾Î±ÎºÎ¿Î»Î¿Ï Î¸Î¿Ïν να ÏιÏÏεÏÎ¿Ï Î½ ÏÏι αÏοÏελεί γνήÏιο ÎÏγο ÏÎÏÎ½Î·Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Botticelli. Î ÏÎ¯Î½Î±ÎºÎ±Ï ÎºÎ±ÏαδεικνÏει Ïην μεγάλη ÏÏ Î¼Î²Î¿Î»Î® ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î»Î»Î¹ÏÎÏνη ÏÏην ιÏÏοÏία ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏοÏÏÏογÏαÏίαÏ, αÏομακÏÏνονÏÎ±Ï Ïο ενδιαÏÎÏον αÏÏ Ïα ÏÏαÏικά ÎÏγα εμÏÏοÏÎ¸Î¯Î±Ï ÏÏεÏÏ (ÏÏοÏίλ) και ειÏάγονÏÎ±Ï Ïην ÎµÎ»ÎºÏ ÏÏική ÏÏάÏη ÏÏν ÏÏιÏν ÏεÏάÏÏÏν, εÏιÏÏÎÏονÏÎ±Ï ÎÏÏι ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î¸ÎµÎ±ÏÎÏ Î½Î± αλληλεÏιδÏάÏÎ¿Ï Î½ άμεÏα με Ïα θÎμαÏα ÏÏν ÏινάκÏν. Î Smeralda εμÏανίζεÏαι με Ïο ÏÎÏι ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏο ÏλαίÏιο ÏÎ¿Ï ÏαÏαθÏÏÎ¿Ï , μια άλλη εÏεÏÏεÏη ÏÎ¿Ï Botticelli, αμÏιÏβηÏÏνÏÎ±Ï Î³Î¹Î± άλλη μια ÏοÏά Ïην Îννοια ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏαγμαÏικÏÏηÏÎ±Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ καÏαÏÏίÏÏονÏÎ±Ï Ïο εÏίÏεδο ÏÎ·Ï ÎµÎ¹ÎºÏÎ½Î±Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ Ïον ÏÏÏο μεÏÎ±Î¾Ï Î¸ÎμαÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ θεαÏή. ΥιοθεÏÏνÏÎ±Ï Î±Ï ÏÏ Ïο νÎο ÏÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏοÏÏÏογÏαÏίαÏ, ο Botticelli Îδινε μια αίÏθηÏη κίνηÏÎ·Ï ÏÏÎ¹Ï ÏÏοÏÏÏογÏαÏÎ¯ÎµÏ ÏÎ¿Ï , αÏοδίνονÏÎ±Ï ÏÏοκληÏικά ζÏή ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏίνακÎÏ ÏÎ¿Ï . Îι καινοÏÎ¿Î¼Î¯ÎµÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î»Î»Î¹ÏÎÏνη εÏαναλήÏθηκαν γÏήγοÏα αÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÏ Î³ÏÏÏÎ½Î¿Ï Ï ÏÎ¿Ï . ..

SAINT AVIA (THE JAILED WOMAN)c. 1500 France[1400]

SAINT AVIA (THE JAILED WOMAN)c. 1500 France[1400]ΣÎÎÎÎΩΣÎÎΣ[10]. https://www.facebook.com/TheMythologi.... MiloÅ¡eviÄ 2021.[1000]. Pierguidi 2002.[1100]. Heckscherthe 1956.[1200]. https://www.facebook.com/permalink.ph.... https://www.samfogg.com/exhibitions/2...

ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎΡÎΦÎÎ

https://www.researchgate.net/publicat..., P. 2021. "The Byzantine Renaissance as the predominant source and impetus for the Italian Renaissance - Theodore Gaza in Mantua, Ferrara, Rome and Naples and Nicolaos Leonicos Tomeos in Venice, Florence and Padua," in Conference: The Byzantine Renaissance as the predominant source and impetus for the Italian Renaissance - Theodore Gaza in Mantua, Ferrara, Rome and Naples and Nicolaos Leonicos Tomeos in Venice, Florence and Padua -At: Laboratório de Estudos Medievais (LEME/UNIFESP) and by the Laboratório de Estudos Mediterrânicos e Bizantinos (LÃMEB), based at the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP), Brazil.

https://ia801200.us.archive.org/1/ite... J. H. Jenkins. 1963. "The Hellenistic Origins of Byzantine Literature," Dumbarton Oaks Papers 17, pp. 37+39-52.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/23206766

Pierguidi, S. 2002. "Botticelli and Protogenes: An anecdote from Pliny's Naturalis Historia," Notes in the History of Art 21 (3), pp. 15-18.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/43872969..., W. S. 1956. "'Anadyomene' in the medieval tradition: (Pelagia - Cleopatra - Aphrodite). A prelude to Botticelli's 'Birth of Venus'," Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek (NKJ) / Netherlands Yearbook for History of Art 7, pp. 1-38.

https://www.ft.com/content/026a19fc-f..., T. 2022. "Why âwoman in the windowâ is such an enduring theme in art," FT Magazine - Visual Arts, <https://www.ft.com/content/026a19fc-f... (14 August 2022).

ÎονιδάÏÎ·Ï Î. 2022. "WOMAN AT THE WINDOW. ÎÎ¥ÎÎÎÎÎ ÎÎΤÎΠΤÎÎ¥ÎΥΣΠÎΠΠΤΠÎÎΩΡÎÎÎ (καÏαÏκοÏία - ÏαÏακÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Ïα)," ÎÎÎÎÎΤÎΣÎ, <https://dnkonidaris.blogspot.com/2022... (14 August 2022).

https://www.academia.edu/48069027/Bot..., A. and C. Elam, eds. 2019. Botticelli Past and Present, UCL Press.

Published on August 15, 2022 05:58

No comments have been added yet.