Before They Became Woke: Eugene McDaniels’ 'Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse' by Mark Anthony Neal

Before They Became Woke: Eugene McDaniels’ Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse

by Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

In this moment of wokeness (always, already under assault), the enduring search is not only for a politics of equity and justice, but for a ready-made soundtrack – an easily accessible streaming playlist to be more specific – in support of those aspirations. In some ways the latter has proved as elusive as the former at a time when attention spans are bombarded with an unprecedented amount of information and the “song of the week” takes a back seat to the Tik-Tok post of the hour. What a century of protest and protest music has offered is that revolution, in sound and otherwise, is a slow cooked meal, where some of the ingredients are often found in the cupboards – the archives – of history and struggle.

For that greatest generation of activists, those who were involved in the early days of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), they found their inspiration in the labor songs of earlier generations, such as Pete Seeger and Lee Hays’ “If I Had a Hammer” (1949) or “We Shall Overcome” which was made popular at the Highlanders Folk School, which trained a generation of activists like Ella Baker and Rosa Parks. Today’s activists and agents of change might find their own inspiration in the archive with one of the great obscure gems of protest music, Eugene McDaniels’ Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse, which was released in 1971, a watershed moment for Black political music.

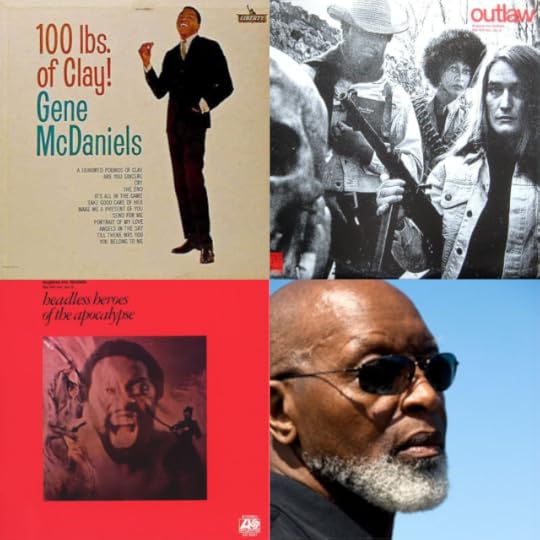

As the 1960s began and the Civil Right Movement gained the momentum that would lead to the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965, Eugene McDaniel was charting a career as a pop singer with songs like the timeless “A Hundred Pounds of Clay,” and “Tower of Strength”. Though the Civil Rights Movement produced pop anthems like Sam Cooke’s “A Change is Gonna Come” and Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind,” few artists in the early 1960s could risk recording music that blatantly addressed the political realities of the era. As the non-violent protest of the Civil Rights Movement ceded space to anti-Vietnam protests and the militants of the Black Power Movement, the music captured the new radicalism, where even some of the musical avatars of Black respectability in the 1960s began to push the political envelope including The Temptations (“Ball of Confusion”) and most famously James Brown, with “Say It Loud”.

Eugene McDaniels was not immune to the moment or the new music, and reemerged after a brief exile in Europe, bringing the liberation movement into focus in his music. Two early contributions from McDaniels in this era appeared on Jazz albums that were released 1969. McDaniels co-wrote the title track and provided lead vocals on Bobby Hutcherson’s Slow Change, as well as two other tracks (“Now” and “Hello the Wind”). An overlooked gem in its own right, McDaniels work with Hutcherson was overshadowed by a recording of his song “Compared to What.” Though the song first appeared as the opening track on Roberta Flack’s debut First Take, released in June of 1969, it was a live version of the song performed by saxophonist Eddie Harris and pianist Les McCann (Flack’s manager at the time) at the 1969 Montreux Jazz Festival (also in June of 1969) that became a crossover hit as the lead single of the duo’s Swiss Movement. The album topped the Jazz charts and the single peaked at 35 on the Billboardpop charts in January of 1970.

Originally written in 1966, the original target of McDaniels’ ire (“The President, he's got his war,folk don't know just what it's for”) was President Lyndon B. Johnson, but by the time the Harris/McCann version was released such ire was directed at then President Richard M. Nixon. McDaniels would keep his eyes on that prize when he went back into the studio to record Outlaw for Atlantic Records in 1970. Released a year before Marvin Gaye’s seminal What’s Going On, Outlawoffered a multifaceted perspective on those living on the margins, from the poor, homeless citizens of “Welfare City” to Black youth on a track like “Black Boy”. But McDaniels also took on the status quo on songs like “Love Letter to America” and especially on “Silent Majority”, where he juxtaposed the so-called electorate behind President Nixon’s victory in 1968 to quite another “silent majority” – “Silent majority is calling out loud to you and me / From Arlington Cemetery” – in reference those American citizens that died in the Vietnam conflict.

McDaniels was not done; a single “Tell Me Mr. President”, arranged by the great Thom Bell and produced by Joel Dorn appears in early 1971with little fanfare. It might be considered a warning shot; McDaniels took more explicit aim when Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse was released later in 1971. More than fifty years after its release, Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse remains one of the most blatantly political musical recordings ever released commercially by a major label. The album contained critiques of blue-eyed soul (“Jagger the Dagger”), examined the phenomenon of “shopping while Black” (“Supermarket Blues”)—years before “racial profiling” entered into the national lexicon—and the futility of race hatred (“Headless Heroes'').

“The Parasite” (dedicated presumably to Buffy Sainte-Marie) was McDaniels’ most stinging critique though, as he gets at the root of American Imperialism and its relationship to the genocide of America’s native populations. On the track McDaniels describes some of the early settlers as “ex-hoodlums” and “jailbirds” who used “forked tongues” in their drive to pollute the water and defile the air. Referencing America’s ideology of “Manifest Destiny”, McDaniels sarcastically sang that as “agents of God, they did damned well what they pleased.” To capture the annihilation brought upon the Native populations, McDaniels plucks a stringed instrument in a way that replicates Native resistance by way of bow and arrow. McDaniels, whose vocal style was not unlike that of Chuck Jackson and Brook Benton, two peers who crossed over in the early 1960s, screams at points in the song, as if mimicking the ways that “respectability” politics and civility were coming undone.

Shortly after the release of Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse, McDaniels was unceremoniously “dropped” from Atlantic. McDaniels apparently caught the attention of the White House with a not so thinly veiled shot at the Nixon administration and their “Law and Order” domestic policy (“rewriting the standards of what’s good and fair/promote law and order/let justice go to hell”). As the story goes, then Vice-President Spiro Agnew reached out to Atlantic founders Armet and Neshui Ertegun, and McDaniels was released from his contract. McDaniels recalled thirty years later, “It was a Black man in open, conscious resistance of the power that was trying to keep him enslaved—that was me…At last I had a chance to say what I believed in my deepest heart about politics, slavery, and about the genocide of Indians.” (Pitch Magazine, 2001)

Even with the setback, other artists began to record McDaniels’ songs; his “Sunday and Sister Jones” appears on Flack’s 1972 album Quiet Fire (he also sings backup with McCann on the album’s “To Love Somebody”) and also contributed “River” on Flack’s career defining album Killing Me Softly (1973). Most famously Roberta Flack recorded McDaniels’s “Feel Like Makin’ Love,” which is among the most well known pop recordings from the period. With his political points made, McDaniels seemed to be trying to find a way to function within the recording industry on his own terms. He did so by also producing other artists like Lenny Williams, who also covered “River”, Merry Clayton(Keep Your Eye on the Sparrow), and Gladys Knight & The Pips(2nd Anniversary) among others in the 1970s and much later producing tracks for Nancy Wilson and Phyllis Hyman in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse might have remained an obscurity if not for the crate diggers of the late 1980s and early 1990s who liberated it from the metaphoric dust bin. Out of print for more than 20 years, Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse found its way into the music of A Tribe Called Quest, Organized Konfusion, The Beasties and Pete Rock and CL Smooth as samples. The original recording quickly became a collectable and bootlegged CD pressings of the album also appeared. In his 2001 profile of McDaniels in Pitch Magazine, writer Shawn Edwards notes the irony that Atlantic continues to collect royalties for the album’s sampled use.

When Coke decided to launch an ad campaign in 2003 featuring “Compared to What?” McDaniels’ profile increased. The intent of the song seemed lost on a generation of caffeinated fizz drinkers, even as the commercials, which featured Common, Mya, Amel Larrieux, Angie Stone and Musiq, was released as it was increasingly clear that the United States was going to invade Iraq. Even as it was being reclaimed, the song, and to some extent, McDaniels’ legacy was being gutted of its political impulses. Thankfully, Eugene McDaniels, lived long enough to hear Meshell Ndegeocello’s brilliant reading of “Compared to What?,” on the soundtrack of Talk to Me, the biopic of one of McDaniels’ political contemporaries, Petey Greene, and the release of the John Legend/The Roots collaboration Wake Up!, which featured a version of “Compared to What?.”

In the past decade, and certainly since the emergence of Black Lives Matter, a generation of artists have been able to leverage their celebrity and social media presence in the name of social justice, and in a few cases, some policy reforms. In most cases they were able to do so with little sustained damage to their commercial livelihoods. While we can celebrate their abilities to be both woke and paid, it’s incumbent to remember the names of those forebears, who sacrificed fame, livelihoods and safety for their political beliefs; names like Billie Holiday, Josh White, Nina Simone, and Sam Cooke to name just a few, and certainly Eugene McDaniels is among them.

***

Mark Anthony Neal is the James B. Duke Distinguished Professor of African & African American Studies at Duke University, and the author of several books including the just published Black Ephemera: The Crisis and Challenge of the Musical Archive (NYU Press) and What the Music Said: Black Popular Music and Black Public Culture.

*

A version of this essay appears as part of the 50th Anniversary Limited Vinyl Edition of Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse.

@font-face {font-family:Helvetica; panose-1:0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1342208091 0 0 415 0;}@font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:roman; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:3 0 0 0 1 0;}@font-face {font-family:Calibri; panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:swiss; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536859905 -1073732485 9 0 511 0;}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0in; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;}.MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;}div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;}

@font-face {font-family:Helvetica; panose-1:0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1342208091 0 0 415 0;}@font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:roman; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:3 0 0 0 1 0;}@font-face {font-family:Calibri; panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:swiss; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536859905 -1073732485 9 0 511 0;}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0in; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;}.MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;}div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;}

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers