Sic Transit Transitory: Yes. Sic Transit Inflation?: Unfortunately not.

So today inflation as measured by the Consumer Price Index checked in at 8.6 percent annualized. Which is an uptick in the rate rather than the promised easing.

Sic transit transitory.

The Queen of Transitory, Janet Yellen (Jerome Powell being the King) acknowledged as much earlier this week in Congressional testimony, admitting that her prediction had been wrong. Whoopsie!

One wonders about her (and Powell’s and the rest of the herd’s) mental model of inflation, especially under current circumstances. The usual explanation is some version of the Phillips Curve inflation-unemployment tradeoff. Which is stupid because it is just a correlation, and a worthless one at that since it is about as stable as Amber Heard.

But even that idiocy obviously won’t fly here, so Yellen mumbled about COVID and supply chains and Putin and blah blah blah (as well as holding forth on gun control and abortion, which are OBVIOUSLY primary responsibilities of the Treasury Secretary). These explanations are also inadequate.

Insofar as COVID is concerned, arguably the policy response to it (not COVID itself) shifted back supply curves as stores were closed and people stayed home from work. But those restrictions peaked in early-2021 and have been easing then, so can’t explain by themselves accelerating inflation in the subsequent months.

Yes, COVID has had lingering effects on certain sectors that have constrained supply while demand has rebounded. For example, a lot of truckers that left the industry in 2020-2021 haven’t come back. Interestingly, trucking schools shut down during the pandemic, which has constrained the flow of new labor to the market. In industries such as lumber and oil refining, the largely policy-driven collapse in demand in 2020 led to actual disinvestment and a loss of capacity. We saw the impacts of that in the lumber market a year ago, and are seeing it in the markets for refined products now.

But those factors alone cannot explain the recent spikes: demand has to be part of the equation as well.

Also, supply constraints (and supply chain bottlenecks) cannot explain increases in the general price level, especially as measured by broader measures such as the Producer Price Index and the GDP Deflator. Here’s a straightforward example.

Consider computer chips, inadequate supplies of which hit the auto industry hard, and which are blamed as a major culprit for inflation. Yes, the chip supply constraint limited the production of new automobiles, raising the prices of both new and used cars (which are substitutes for new ones). But, the limitation on the output of automobiles reduced the derived demand for other automobile inputs, such as aluminum, steel, rubber, labor, and capital goods. Ceteris paribus, that should have put downward pressure on the prices of those inputs.

Put differently, bottlenecks increase prices on one side of the bottleneck relative to the prices on the other side. One cannot attribute a rise in the price level (in which the prices of most if not all goods and services are rising, albeit some more than others) to bottlenecks, at least not directly. Bottlenecks can cause prices to fall too. You can’t just look at the impact on the downstream side.

A more indirect story is that by limiting output (and therefore income) bottlenecks cause real income to be lower, thereby reducing the demand for real money balances. Given the nominal supply of money, the only way to equilibrate the now lower demand for real balances with a given nominal supply is to reduce the real value of the money stock by increasing the price level.

Color me skeptical that this can explain the magnitude of the inflation we’ve seen. (The Fed juicing base money by almost 50 percent in 2021 could have added to this impact.)

I therefore am deeply skeptical that supply constraints, attributable to COVID or otherwise, explain the broad rise in prices that has been accelerating over the past year plus.

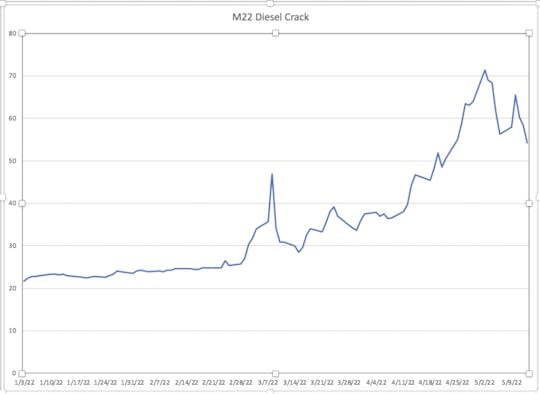

What about Putin, Biden’s favorite scapegoat? Well, the Ukraine War doesn’t really explain the timing. Consider diesel prices.

There was a spike in the crack spread right at the time of the invasion in late-February, but that subsided quickly. The subsequent runup, especially the ramp-up in mid-April, is harder to ascribe to the war and almost certainly reflects some demand side factors.

Furthermore, it usually takes some time for upstream shocks to translate into higher prices at the consumer level (e.g., a wheat price shock impacting retail food prices). Meaning that a lot of the impact of a disruption first occurring in March is yet to have been fully felt. Good news all around, eh?

No, I think that the stock explanations that the likes of Yellen, Biden and the media fall back on to explain the accelerating inflation are woefully inadequate. Supply chain (and the effects of COVID thereon) in particular.

The most plausible explanation to me is the fiscal theory of the price level, developed formally some years ago by Thomas Sargent and recently studied deeply by John Cochrane. In a nutshell, the theory posits that the price level adjusts to equate the real value of government debt to the discounted real value of government primary surplus. Holding primary surplus constant, an increase in government obligations requires a price level rise to reduce the real value of outstanding debt by the amount of the new debt. Similarly, given the level of government debt, any reduction in expected future surpluses requires a rise in the price level. (The theory is obviously a lot more complicated: that’s a Cliffs’ Notes version of the Cliffs’ Notes of John’s book.)

The massive COVID-driven fiscal stimuluses of both Trump and Biden dramatically increased the nominal value of US government debt. Moreover, the clear preference of this administration and Congress is to expand government spending (and debt) further (e.g., student debt forgiveness, among other things). (It will be interesting to see what happens to inflation if there is a big shift in Congress in 2022.)

I would also suggest that the big regulation plus big “green” agenda pursued by this administration and Congress are also inimical to growth, and expectations about growth. (I put “green” in quotes because as I’ve written before, a monomaniacal focus on CO2 is not a balanced environmental policy, and is indeed inimical to the environment in many ways.)

The green agenda is particularly pernicious. BIden and others (not just in the US) keep yammering away about the wonderful transition to green energy that will occur. What this really means is a transition to more expensive energy and lower incomes. Sic transit transition? I wish.

Less growth means lower future GDP means less future government revenue means smaller primary surpluses.

Meaning that both from the debt side and the growth/surplus side the COVID and post-COVID years are, according to the fiscal theory of the price level, a recipe for large increases in the price level. We’ve seen just such an increase. The timing works out. The fact that the increase in prices is broad works out.

This administration–of which Yellen is unfortunately an accurate avatar–not only does not believe in the fiscal theory, but finds it an anathema because its implications regarding the need to restrain government spending and to jettison onerous regulations and its cherished CO2 agenda require it to become, well, Reaganites. So what is likely the right model of the current inflation will never be their mental model.

Which means we will not be able to say sic transit inflation anytime soon.

Craig Pirrong's Blog

- Craig Pirrong's profile

- 2 followers