Five days in June

Today marks the 54th anniversary of the funeral of Robert F. Kennedy. I'm currently reading a book about his presidential campaign—totally coincidental, I might add; I don't have enough foresight to plan this kind of thing—and not long ago finished one examining the evidence against Sirhan. So, what with the occasional flashbacks I've been seeing pop up in the last few days, it's difficult not to have it on the mind, especially if you remember the moment. Here's something I wrote several years ago about those times, lightly edited for improvement. It still holds up pretty well, if I do say so myself.

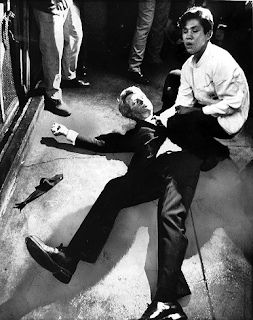

It was the middle of the night when Robert F. Kennedy was shot following his victory in the California primary—arguably the biggest American news event ever to occur during the overnight hours. Kennedy gave his victory speech at a quarter past midnight Pacific time—3:15 a.m. on the East Coast—and in those wee hours of the early morning, many people would get their first news of the shooting not from television, but from radio.* In the days before 24/7 television, it's not hard to imagine people lying in bed with the radio on, unable to sleep, listening to a late-night music program when the news broke, and thereafter continuing to lay there in the stillness of the dark, listening to disembodied voices describing what had happened in far-away Los Angeles.

It was the middle of the night when Robert F. Kennedy was shot following his victory in the California primary—arguably the biggest American news event ever to occur during the overnight hours. Kennedy gave his victory speech at a quarter past midnight Pacific time—3:15 a.m. on the East Coast—and in those wee hours of the early morning, many people would get their first news of the shooting not from television, but from radio.* In the days before 24/7 television, it's not hard to imagine people lying in bed with the radio on, unable to sleep, listening to a late-night music program when the news broke, and thereafter continuing to lay there in the stillness of the dark, listening to disembodied voices describing what had happened in far-away Los Angeles. *According to a contemporary poll, 56% first received the news on radio. And most people didn't even find out until they'd gotten up that morning; less than 20% had heard the news by 5:00 a.m. ET. By 7:00 a.m., however, 15.9% of all homes with television were watching; on a usual morning, the figure was 1.6%

In Minneapolis, Franklin Hobbs was hosting his popular overnight music program "Hobbs House" on clear channel WCCO-AM, and he presented wire-service reports until CBS came on the air with network coverage.* One thing that stands out from these contemporary bulletins is how fresh in the memory the assassination of JFK still was—RFK is often referred to as "the brother of assassinated President John Kennedy." One report talked of Kennedy's eyes being "open but unseeing," and Hobbes, perhaps trying to keep listeners from panicking, cautions that this might be an "overly-dramatic" report.

*Those early reports had Kennedy being shot in the hip; I've never been sure if someone originally misunderstood "head" as "hip," or if they confused the wounds with those of one of the other bystanders who'd been shot.

I've referred in the past to television as being the most intimate form of communications, but radio can be even more intimate, more one-on-one, especially at nighttime. Television reporters talk at you, their words providing a backdrop to the dominant pictures, while radio reporters talk to you, and the effect can be far more intimate.* And so, lacking the images that television could provide, radio reporters were forced to paint word pictures for their listeners, and these disembodied voices, speaking in that lonely darkness of Wednesday morning, create an unreal, almost surrealistic atmosphere.

I've referred in the past to television as being the most intimate form of communications, but radio can be even more intimate, more one-on-one, especially at nighttime. Television reporters talk at you, their words providing a backdrop to the dominant pictures, while radio reporters talk to you, and the effect can be far more intimate.* And so, lacking the images that television could provide, radio reporters were forced to paint word pictures for their listeners, and these disembodied voices, speaking in that lonely darkness of Wednesday morning, create an unreal, almost surrealistic atmosphere. *As any baseball fan can tell you.

Imagine listening to the reports as you lay in bed during those small hours, your bedside alarm clock silently glowing. Perhaps you were agitated, you had to get up and walk around, slipping on your robe, trying to comprehend this latest horror in a year of increasing horrors—as you looked out your window, was the neighborhood shrouded in blackness, with only the radio voices breaking the dead night? Did you lay there, unwilling or perhaps even afraid to turn on the lights, preferring the shelter of the night, your agony a silent and solitary one? Or did lights begin to snap on in houses up and down the block as the news spread, and did you perhaps call a friend or family member yourself, compelled to share your agitation with others?

, .l l l

The television networks scrambled to get back on the air. Tabulation of the vote had been miserably slow, in spite of—or perhaps, as Howard K. Smith noted wryly, because of—new automated voting equipment. Therefore, coverage had already stretched more than two hours beyond the planned cutoff by the time Kennedy came down to the ballroom of the Ambassador Hotel to claim victory. He then left the stage, cutting through the pantry behind the ballroom, headed for a press conference that was never held.

By this time, according to Broadcasting magazine, CBS had already ended their coverage, and in New York ,anchor Joseph Benti was across the street at a bar, unwinding a bit after the long broadcast. As news spread, he raced back to the studio and went on the air with the bulletin. At NBC , the only one of the three networks to be broadcasting from Los Angeles, Frank McGee, having received unconfirmed reports in his earpiece, vamped for a few minutes, keeping the studio coverage live until the report could be confirmed. ABC , the only network yet to project Kennedy as the winner, was in the process of signing off in favor of Joey Bishop's show; the credits were actually rolling when the first report came in, and after a couple of "please stand by" announcements, Howard K. Smith returned with the news.

WPIX in New York broadcast the single word "Shame" for over

WPIX in New York broadcast the single word "Shame" for overtwo hours Wednesday morning as RFK underwent surgery.

Kennedy underwent surgery early that Wednesday morning; expected to last less than an hour, it instead ran for almost four. The networks maintained continuous coverage throughout the morning; in ABC's case, devoting Dick Cavett's morning talk show to commercial-free discussion of the breaking story. (See here and here .)

Kennedy clung to life for over 24 hours, and his passing, like the shooting itself, came in the middle of the night. Throughout Wednesday afternoon and evening, networks provided periodic medical bulletins and special reports, otherwise maintaining a semblance of their regular programming, albeit with subtle changes: ABC cancelled a planned repeat of the murder mystery Laura (featuring Lee Radziwill, Jackie Kennedy's sister). Wednesday's Joey Bishop Show was expanded to two hours, commercial free, and included an interview with Andrew West of Mutual Broadcasting, who had been only feet away from Kennedy when the shots were fired, resulting in a memorable radio broadcast.

Kennedy died just after 4:30 a.m. Eastern time Thursday morning. and the networks remained on the air until noon, returning later in the afternoon for the departure of the plane returning his body to New York. CBS preempted its primetime schedule for continuous coverage, while ABC and NBC presented special broadcasts following an abbreviated schedule. ABC substituted episodes of less violent episodes of The Avengers and The Flying Nun,* and Johnny Carson devoted that night's entire Tonight Show to the assassination. Meanwhile, on NET, Fred Rogers presented the first primetime episode of Mister Rogers' Neighborhood to help parents talk about the assassination with their children.

*The Flying Nun too violent? Oh, yes; that night's storyline involved Sr. Bertrille finding herself in the middle of a mob hit.

Kennedy's body lay in state in St. Patrick's Cathedral in New York throughout Friday. The funeral Mass was held there on Saturday, and then the body was taken by funeral train to Washington, D.C. where he was buried next to his brother on Saturday night.

l l l

YouTube is loaded with television coverage of John F. Kennedy's assassination, and there's a good chunk of broadcast material from Robert F. Kennedy's as well, including the initial broadcasts from all three networks. When hard news wasn't being rehashed, discussion turned to the issues of violence in American (in general) and gun control (in particular), not only on programs like The Dick Cavett Show, but from news commentators as well. If you want proof, look no further than Frank Reynolds and his impassioned commentary on gun control during ABC's Wednesday morning coverage.

These television broadcasts are all fascinating, as they would be to someone who runs a blog called It's About TV!, but it's the radio coverage I want to return to. I began by discussing how the news spread on radio, and thanks to this amazing collection of radio broadcasts we can hear how the coverage proceeds throughout the early morning hours on Wednesday, to the announcement of Kennedy's death Thursday, and the funeral and burial on Saturday. Particularly interesting is Arthur Godfrey's shrewd commentary on his CBS morning show Thursday. Amid the calls for restrictions on guns and other liberties, Godfrey says, people will say that "there ought to be a law." But, he continues, "We can only hope and pray that reason will continue to prevail...the danger at hand, it seems to me, is that men of questionable purpose will find an excuse in what's happened to alter our system, to use our emotional state as a cover for rushing through some repressive laws that purport to cure the ills of society. In my view it's not a time for hysterical action or pejorative oratory." Godfrey was a master of communication, it's true, but even so it's difficult to imagine that a television commentator (other than, perhaps, Ronald Reagan), could make the same connection to an audience.

In much the same way, radio coverage of Saturday's funeral and burial provides a dimension different from that of television. Without the fillers that TV pictures provide, the announcers were forced to describe the unfolding events, and during the many times when nothing at all was happening, their commentary provided nothing so much as an insight into their own hearts. During the funeral, covered on CBS radio by Douglas Edwards and Maury Robinson, the men struggle with the unfamiliar "new" liturgy of the Catholic Church (a hybrid between the old Latin Tridentine rite and the soon-to-be-revealed Vatican II Novus Ordo), all the while explaining the significance of the words and gestures occurring in front of them.

Images of Saturday (upper): Ted Kennedy eulogizes his brother; Leonard Bernstein conducts the New York Philharmonic in the Adagietto from Mahler's Seventh; (lower) a passenger train coming from the other direction kills two in New Jersey; RFK is laid to rest hours behind schedule.

Images of Saturday (upper): Ted Kennedy eulogizes his brother; Leonard Bernstein conducts the New York Philharmonic in the Adagietto from Mahler's Seventh; (lower) a passenger train coming from the other direction kills two in New Jersey; RFK is laid to rest hours behind schedule. Without the pictures, the listener is forced to remember not the sights, but the sounds, of those events: the quivering voice of Edward Kennedy eulogizing his brother; the mournful strains of Mahler's Adagietto accompanying the procession of Kennedy youngsters as they brought the Communion offerings to the altar, the smooth, sad voice of Andy Williams singing "The Battle Hymn of the Republic" as the pallbearers prepare to remove the casket from the Cathedral. Amazingly, near the end of Kennedy's funeral, a news update informs us that James Earl Ray, accused of assassinating Martin Luther King a mere two months before, had been apprehended in London. News, like death, takes no holiday.

The funeral train taking Kennedy's body from New York to Washington was both a tribute and, in some respects, a fiasco. Two people were killed in Elizabeth, New Jersey by an express train travelling in the opposite direction, and after that the Penn Central shut down northbound rail traffic. The funeral train was almost five hours late in arriving in Washington, travelling slowly to afford the crowds, estimated at perhaps two million people, a better chance to view it. It had been expected that the burial would occur in late afternoon or early evening, and Major League Baseball had rescheduled the day's games to the evening, to start after the ceremony. Instead, the first pitches were thrown as the train continued its slow progress; the actual burial didn't occur until after 10:00 p.m. Eastern. On television the remote images showed the train pulling into Washington's Union Station; on radio, one hears only the lonely ringing of the train's bell. As the motorcade processes down Constitution Avenue to Arlington, a radio reporter apologizes for not being able to provide better coverage, but the darkness combined with the leafy canopy formed by the trees lining the street served to obscure her view. George Herman, anchoring CBS' radio coverage, mentions the Kennedy people asking CBS to pass along a request to those lining the funeral route and listening to transistor radios that they light a match as the cortege passes by.

l l l

I was eight years old in 1968, and I have more of a personal memory of Robert Kennedy's death than that of John's. I watched the coverage the day through, not really understanding or appreciating what I was saying. I was upset that the baseball game had been preempted, and as the day and night wore on I hung in there, waiting for the Bedtime Nooz , Channel 4's late-Saturday night satiric comedy news show. When it did air, as the hour approached midnight, it was done straight, without humor. Again, I was disappointed.

Watching and listening to the events from that week (covered in fascinating detail in this issue of Broadcasting ) has provided an opportunity to reflect on everything that happened, and how it was broadcast. Nineteen sixty-eight had already been an eventful, grim year: the Tet Offensive, Eugene McCarthy's challenge to President Johnson and LBJ's subsequent decision not to seek reelection, the assassination of Martin Luther King, race riots, war protests, and now this. Still to come was the tumultuous Democratic convention in Chicago and the election; one of the few bright spots was Apollo 8's memorable Christmas Eve trip around the moon.

As such, I think the American people were a more cynical lot, numbed somewhat to the events that seemed to cascade, one after another, throughout the year. Whereas JFK's assassination was truly shocking, if not incomprehensible, by June of 1968 the assassination of Robert Kennedy was all-too believable. And perhaps that's what made it such a deeply sad event for so many, for without the anesthesia of shock to cushion the blow, the emotions that had been rubbed raw were there for the taking. It was so stunning, so unexpected, so quick. I freely admit that I am not now and never have been a fan of the Kennedys politically; in most issues, we're about as far apart as can be. But the events of that week in June worked on so many levels: the political, the personal, the familial. And as the day drew to an end, and the country worried about what might come next,

That night, in recounting the "stunning tragedy" of Robert F. Kennedy, ABC's Keith McBee reviewed the "unique, painful events" of Saturday, June 8, 1968. Those two descriptions combined the best of the elements we've discussed, picture and sound. It was, indeed, a unique, painful, and tragic week. TV

Published on June 08, 2022 05:00

No comments have been added yet.

It's About TV!

Insightful commentary on how classic TV shows mirrored and influenced American society, tracing the impact of iconic series on national identity, cultural change, and the challenges we face today.

- Mitchell Hadley's profile

- 5 followers