A woman in charge – three books set between 1860s and 1815

WORKING DRAFT

A woman in charge – three books set between 1860s and 1815

Thanks to the Ed Baugh Lecture held on May 9, 2022 I first heard about what could be considered as the first novel by a Jamaican woman. A notable fact, but I read the novel a few days later and it is remarkable that it is set in 1915-1917 about a Jamaican woman and her banana estate. The author, I think, gives us the world as it would have been seen by a contemporary observer and it led me to think about two other books with women in charge: Far From the Madding Crowd by Thomas Hardy and Gone With the Wind by Margaret Mitchell.

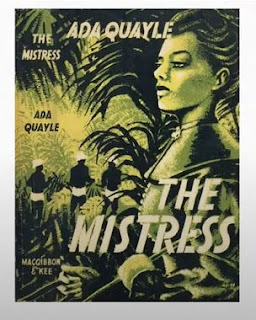

The lecture was delivered by Head of School of Literature, Drama and Creative Writing, Professor Alison Donnell’s theme was: The Missing Mid-Century West Indian Woman Writer and Another Quarrel With History. She addressed three writers, Ada Quayle, Jamaican and author of one novel, The Mistress (1957); Edwina Melville, Guyana, journalist and short story writer; and Monica Skeete, Barbados, novelist and short story writer.

The protagonists of the three books that came to my mind: GWTW, FFTMC and The Mistress are similar in age and outstanding circumstances outside of their control caused them to come into control of farm land. I considered the books on three points: steward of the land; language and lovers.

Following the death of her uncle in the 1860s, Englishwoman Bathsheba Everdene, at about age 18 or 20, and without any agricultural or managerial experience, decides to manage her inheritance Weatherbury the sheep and grain farm.

Upheaval caused by the American Civil War in the 1860s led nineteen-year-old twice widowed and mother Scarlett O’Hara to assume the running of her family’s ruined cotton plantation as her father did not have the will to carry on.

In 1916, sixteen-year-old Jamaican Laura Pettigrew unexpectedly inherits Newbiggin after her mother dies as the result of an accidental overdose of an Obeah spell set on her by her coachman.

Bathsheba makes it a point to consider Weatherbury as her means to independence from the control of a man and she admirably makes the proper running of it her priority. As Hardy allows her to say to the workforce, “I shall be up before you are awake; I shall be afield before you are up; and I shall have breakfasted before you are afield. In short, I shall astonish you all.”

The book turns its attention to her relationships with men as an equal, with farm life being the backdrop for her determination and the rural landscape.

As a plantation manager and matriarch, Scarlett, lives in ruin and displays a determination that nothing material is too much for her to bear. She rages while watching her cotton harvest burn, at the hands of the republican army, “As God is my witness they're not going to lick me. I'm going to live through this and when it's all over, I'll never be hungry again. No, nor any of my folk. If I have to lie, steal, cheat or kill. As God is my witness, I'll never be hungry again”.

Not written in the high literary style of Hardy, Quayle nonetheless demonstrates several times Laura’s determination to make her farm productive. The possible reason why this book has remained in obscurity is the strength of character was many times accompanied by the unvarnished brutality that the mistress delivered to her workers. This renders Laura ignoble while Bathsheba and Scarlett are heroines.

The language of The Mistress is notable in that Laura speaks the same Jamaican language as her workers, on that point, they are one. They also worship at the same church that is on her property. In addition to attending church though, the workers also have their own religious ceremonies and also patronize the obeahman at times.

Bathsheba, however, does not speak like her workers and it is her language and customs that cause her to separate herself from suitors to find a husband who satisfies her cultural tastes.

Scarlett speaks differently from the enslaved persons who work her plantation but there is complete understanding between them.

Each of these three landowning women consider themselves free to choose a suitor or a lover. In the opening pages of The Mistress, Laura has taken her neighbour Neil Naunton as her lover and even when he lets her down financially and also by taking on her neighbour as his fiancée, for a long time she is determined to love him and only him but she finally accepts that she is being used for her money by him.

Bathsheba allows herself to fall in love with Sergeant Troy whom she marries and who brings her towards financial ruin and also impregnates her worker.

Scarlett, on the other hand, had more complex emotional outings. She loved the mild-mannered Ashley Wilkes whom she could not have, and when he died became attracted and connected to Rhett Butler, who had a domineering character.

One question to me was how much did The Mistress borrow from GWTW. I think nothing at all. The character of Laura was immensely Jamaican in speech and mannerisms. The author also had good knowledge of the land and farming in Jamaica and this came out in her descriptions. The tension between expatriate workers, peasants, black overseer, white pastor, coloured wealthy relative and the sexual determination of women of every colour seems to be island based. Also, in FFTMC and GWTW the lead women travelled in carriages while Laura was an excellent on horseback, the novel gives us many examples of her riding.

The poem on which FFTMC gets its name, "Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard" is apt for the stories around Bathsheba, Scarlett and Laura Pettigrew. The poem pays tribute to countryfolk whose hearts and passions were probably as grand as any leader of nations or grand artists or philosophers.

As it says in the 8th and 9th stanzas: “

Let not Ambition mock their useful toil,

Their homely joys, and destiny obscure;

Nor Grandeur hear with a disdainful smile

The short and simple annals of the poor.

The boast of heraldry, the pomp of pow'r,

And all that beauty, all that wealth e'er gave,

Awaits alike th' inevitable hour.

The paths of glory lead but to the grave.”

But, these thoughts started because of the 2022 Ed Baugh Lecture, so to him I must give the privilege to wrap these characters together, and his poem Elemental allows me to do so. It is a poem of carrying on through unknown perils and to rejoice at the end for bravery to have made the journey.

I would have words as tenacious as mules

to bear us, sure-footeed

up the mountain of night

to where, at daybreak;

we would shake hands with the sun

and breathe the breezes of the farthest ocean

and, as we descended,

in sunlight,

We would be amazed

to see what hazards we had passed.

END