“I am counted with them that go down into the pit”

Thanks for reading Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli ! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

On an almost sheer hillside, the Church of St. Peter in Gallicantu stands on the eastern slope of Mt. Zion. A golden rooster rises from the domed steeple. Indeed roosters’s crows can be heard all over the adjacent city of David. “Gallicantu” means “cock’s crow” in Latin, and the church pays homage to Christ’s prophesy that Peter would deny him three times “before the cock crows.” It’s here that Peter— the first one to name Christ rightly (“You are the Messiah!”)— warms himself by a charcoal fire, too cowardly to admit he’s even heard of Jesus of Nazareth and too cold to care that his own Galilean accent gives him away.

Jesus? Jesus of Nazareth? Never heard of him.

“I do not know the man.”

x3

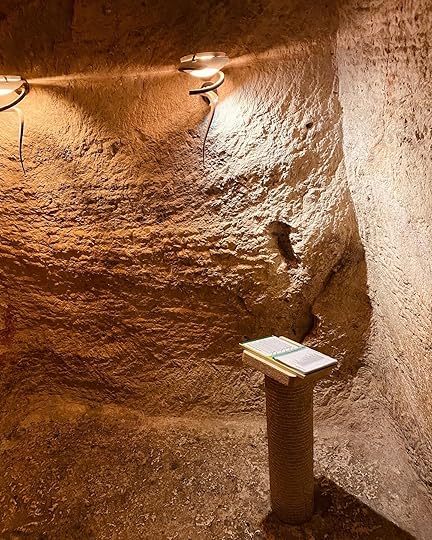

Peter’s threefold denial of Jesus is recorded in all four Gospel accounts of the Passion, and the evangelists report that the scene of Peter’s betrayal is the courtyard of the high priest Caiaphas. Thus, it’s not surprising the Church of St. Peter in Gallicantu, on its lower levels, contains both a guardroom and a prisoner’s cell hewn out of bedrock. Much like diplomatic offices today, in Jesus’s day, the position of high priest was less a religious role and more a political position purchased at a great price. The high priest functioned as the local municipal officer, not unlike a mayor, so it’s not surprising that Caiphas’s palace would contain a jail cell. The guardroom at St. Peter in Gallicantu contains wall fixtures to attach prisoners’ chains. Holes in the stone pillars would have been used to fasten a prisoner’s hands and feet when he was flogged. Bowls carved in the floor are believed to have contained salt and vinegar, either to aggravate the pain or to disinfect the wounds. The prisoner’s cell at Gallincantu not only offers an arresting insight into where Christ spent the night before he was crucified, it also conveys— in a way that an abstract, visualized crucifixion never could— the abject and utter hopelessness that must have enveloped Christ in those final hours. The only access to the bottle-necked jail cell at Gallicantu is through a shaft cut in the bedrock above. Having been beaten and flogged, Jesus would have been bound and then lowered through the hole in the rock by means of a rope harness.

From the floor of the pit to the top of the hole is twenty-five feet. Plus, the prisoner is bound. Once Jesus is down there, inside the pit, there’s no way out. There’s no hope. There is no one.

Standing in the pit today at Gallicantu, I was overwhelmed by the sensation of loneliness that surely accompanied Christ to the cross. While his friend Peter is above ground, just outside the palace walls, Jesus may as well be dead already, hidden like diamond deep in the dirt. If not earlier, Christ’s cry of forsakenness surely started here.

Today, a simple, spare lectern with a spiral bound notebook rests on the floor of the pit. The notebook contains Psalm 88 transcribed in hundreds of languages, from Armenian to Ukrainian. To an extant that will make you second-guess your functional atheism, Psalm 88 seems to refer to Christ as he languished in a dark stone hole. Christ alone in the pit seems to have been on the mind of God long before God was in Christ.

Psalm 88 reads:

“O lord God of my salvation, I have cried day and night before thee:

Let my prayer come before thee: incline thine ear unto my cry;

For my soul is full of troubles: and my life draweth nigh unto the grave.

I am counted with them that go down into the pit: I am as a man that hath no strength:

Free among the dead, like the slain that lie in the grave, whom thou rememberest no more: and they are cut off from thy hand.

Thou hast laid me in the lowest pit, in darkness, in the deeps.

Thy wrath lieth hard upon me, and thou hast afflicted me with all thy waves.

Thou hast put away mine acquaintance far from me; thou hast made me an abomination unto them: I am shut up, and I cannot come forth.

Mine eye mourneth by reason of affliction: Lord, I have called daily upon thee, I have stretched out my hands unto thee.

Wilt thou shew wonders to the dead? shall the dead arise and praise thee? Selah.

Shall thy lovingkindness be declared in the grave? or thy faithfulness in destruction?

Shall thy wonders be known in the dark? and thy righteousness in the land of forgetfulness?

But unto thee have I cried, O Lord; and in the morning shall my prayer prevent thee.

Lord, why castest thou off my soul? why hidest thou thy face from me?

I am afflicted and ready to die from my youth up: while I suffer thy terrors I am distracted.

Thy fierce wrath goeth over me; thy terrors have cut me off.

They came round about me daily like water; they compassed me about together.

Lover and friend hast thou put far from me, and mine acquaintance into darkness. “

When I was a student at Princeton, I took a class on the Death of Jesus. Our professor, Dr. Donald Juel, began the first session of the course with the obvious question, “Why did Jesus have to die?” You don’t even need to be a Christian to know many of the answers that popped up from those who raised their hands. Down through the centuries, the theologians have called such explanations to Dr. Joel’s question, “atonement theories.”

Jesus dies to pay our debt of sin, some explain.

Jesus defeats the power of Death and Sin, others answer.

Jesus is the Second Adam.

Jesus is our Passover.

Jesus is our Ultimate Scapegoat.

Say theologians.

In one sense, the eerie and unmistakable manner in which Psalm 88 prophetically foreshadows the pit in which the Man of Sorrows is imprisoned lends credence to the argument that the cross of Christ is a work of divine necessity. As Caiphas’s crooked cops lower the beaten Jesus down into the bedrock hole clearly, we could conclude, some predetermined plan of the Father for the preexistent Son is clicking into gear.And yet—The unyielding silence of the hewn out hole, the sheer solitariness of the pit beneath the palace, demand, I believe, a more mundane and everyday explanation.

It’s perhaps a more threatening explanation too.

Jesus dies because we killed him.

The theologian Gerhard Forde writes that conspicuously missing from the way most Christians speak of the crucifixion is the brute fact that we killed him. We’ve so pushed the cross into the realm of theory, anchored it to divine necessity (what Forde calls “covering the cross with roses”) that we forget the cross was an event, in actual history, as real as any story in the newspapers, the end result of a basically simple story: In Christ, God came preaching the unconditional forgiveness of sins for sinners who do not deserve it, and we killed him for it. Jesus is the one in whom God did God to us. He did God’s mercy and forgiveness to us. He bore relentless witness to it; therefore, he had to die. And not just die, his reckless message had to be hammered into oblivion.

Well, first we beat him and then dumped him in a hole in the basement while we figured out how to justify it ex post facto.

I stood this morning in the cold, dark pit at the bottom of the chief priest’s palace, and I thought that, actually, perhaps the best “explanation” for the death of Jesus is that Jesus died because the very best of society— church and state, soldiers and citizens— simply agreed with Caiphas.

“We have no king but Caesar!” the chief priest insists to Pontius Pilate.

We conveniently forget—

Judaism was a shining light in the ancient world, offering not only a visible testimony to God who made the heavens and the earth but a way of life that promised order and stability and well-being of the neighbor. And in a world threatened by anarchy and barbarism, the Roman empire brought peace and unity to a frightening and chaotic world. The people who did away with Jesus— Pilate and his soldiers, the chief priests and the Passover pilgrims gathered in Jerusalem— they were all from the best of society not the worst. And they were all doing what they were appointed to do. What they thought they had to do. What they thought was necessary for the public good.

The chief priests’s reasoning (It’s better for one man to die than for all to die…”) is not only a perfectly rational position it’s the best explanation for how Jesus spent his last night in a cold, dark hole as quiet as hell.

Theologians give explanations and theories:

Jesus had to die in order for God to be gracious.

Jesus had to die in order for God to forgive us of our sin.

Jesus had to die to pay a debt we owed but could not pay ourselves.

I’m not arguing that such theories are wrong or unhelpful or contrary to scripture. Many of them are quite helpful in illuminating the crucifixion. But as I listened to Psalm 88 echo underneath what was once Caiphas’s palace, I couldn’t shake the conviction that they are not the best explanation for why Christ was forsaken in the pit. The best explanation for Jesus, like Joseph, being dumped in a hole in the earth and left for dead is the bitter news that this is the only possible conclusion to God taking flesh and coming among us. In Christ God gets close, and we respond by pushing him as far away from us possible, first in a hole hewn in bedrock and later pushed out of the world on a tree.

The theologians attempt to give us answers for the crucifixion.

But the Passion stories themselves leave us to wonder, simply, if this is the best we can do?

The theologians explain.

The Passion stories leave us to wonder if the only possible result of God-with-us—God with people like us— is us dumping God in a hole like so much rubbish, a pit where God-with-us is made all alone.

The horrific silence of Christ’s hole should chasten us who are quick to find good news in an even more brutal experience.

I left the pit under Caiphas’s palace today thinking, “Isn’t it ironic? The only person who can touch us and heal us and forgive us and make us whole was dumped in a basement hole, forsaken, and left for dead.”

What’s true of his garden tomb is true of his hole in the bedrock, but I think it took the latter today to help me realize the former: our only hope in this world is that God will not leave him there.

Share Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli

Read Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli in the new Substack appNow available for iOSGet the app

Read Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli in the new Substack appNow available for iOSGet the app

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers