Should we make it our business to teach the business of being a writer?

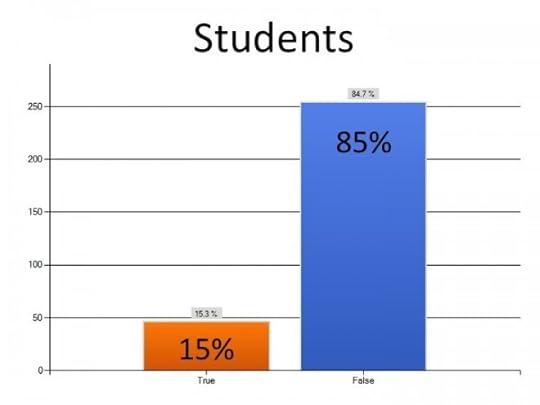

Here's the question I asked both MFA faculty and students on the survey.

MFA programs should avoid "professionalization" and "business" issues related to the writing life, such as discussions of the market and what sells.

And here are the results:

No surprise there!

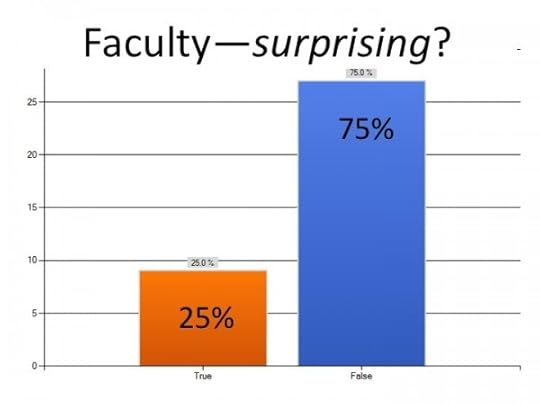

I was kind of blown away by how many faculty said false.

This might surprise you: I selected TRUE. Let me explain that. And let's talk about what we mean by "professionalization."

Which business are we preparing them for: academia or publishing?

I was trying to make a distinction between:

academic professionalization of grad students (creating a CV, how to apply for academic positions, how to give a "job talk")

non-academic professionalization (creating a resume, how to write a query letter, synopsis, or book proposal, how to enter the publishing world).

The former activity almost always happens in English departments, especially those with PhD programs. In my MFA program, the creative writers prepared themselves for the job market by going to meetings for PhD students on "How to enter the profession via the academic job search." We creative writers translated for our own purposes (dissertation = book manuscript, etc.) and sought additional assistance from the CW faculty and writer friends a few years ahead of us. I got very little MFA-specific guidance in how to pursue academic employment, but I did get something, even if it was pitched to PhD's, not creative writers.

The latter activity, non-academic professionalization, which we'll call "How to get published," or "What to do next," sometimes happens in MFA programs, but not often in classes, per se. You're more likely to find it happening in the co-curriculum (delivered via panels, visiting writers series, info sessions) or in one-on-one sessions between thesis advisee and adviser.

I got my MFA long ago in 1995, and back then, my program didn't explicitly address any of these things:

how to submit work to magazines

how to find an agent

how to pitch a nonfiction story to a national magazine

how to do a book proposal

how to apply for grants and fellowships

how going to writers' conferences might help me find new writing peers and possible blurbers

And I definitely didn't learn anything about how to build and maintain a website or online presence. (It was 1995. We were barely using email then.)

These days, I do talk about these things explicitly–at the end of my advanced undergraduate and graduate courses. If you check out the syllabus of my novel-writing class, you'll see that I teach them how to write a pitch, query, and synopsis. I show them how to format a book manuscript. I show them how to submit to literary magazines and how to learn from rejection.

Dangling the Carrot

If you encourage someone to embark on a big thing, dangle a carrot in front of them so they'll finish it. I tell my students, "If you keep writing this book and revise it and make it as perfect as you can, send it to me and I'll see what I can do to help you." A few weeks ago, one of my former undergrads got an agent who is going out with the novel my student started in my Senior Seminar. In this case, I was able to help a student directly, although most of the time, my help is more indirect, more like pointing former students in the right directions or encouraging them not to give up.

If you encourage someone to embark on a big thing, dangle a carrot in front of them so they'll finish it. I tell my students, "If you keep writing this book and revise it and make it as perfect as you can, send it to me and I'll see what I can do to help you." A few weeks ago, one of my former undergrads got an agent who is going out with the novel my student started in my Senior Seminar. In this case, I was able to help a student directly, although most of the time, my help is more indirect, more like pointing former students in the right directions or encouraging them not to give up.

Why do so many apprentice writers give up writing? I think it's because they don't know what to do next. They don't know what to do with the books we encourage them to write. They think publishing is a secret society, and they aren't the right sort, they won't get in. I say bullshit. I say read this. I say let's give them some agency, and I don't mean a literary agent.

But I need to tell you this: I'm enormously conflicted about the fact that I do these things.

If writing is a business, should we teach marketing?

Some people think that MFA programs should help students build an online presence. Last year in the Chronicle, Brian Croxall advised PhD students to do this:

…you want to start now in building an online profile so that you'll like what they find. You can start by Googling yourself to see what information is out there already. Then work to grab your own space on the web, whether it's a blog, wiki, static website, or space on Twitter (or all four). In these spaces you should keep your updated CV, materials related to courses you've taught, first drafts of your work, or anything else to help colleagues and potential employers understand your research, teaching, and skill profiles. As guest ProfHacker and friend Dave Parry wrote in a post on academic branding, you want your profile to "demonstrate to the world what type of scholar you are, and what you do." I personally recommend using your real name, as it will establish your online foothold that much more strongly.

Do we really want to teach MFA fiction candidates how to create a website, how to understand the market they're writing for, how to brand themselves? Do most MFA faculty even understand what that means?

Just thinking about this issue makes me itchy–because it's a complete anathema to the way I became a writer, and yet, I know it's incredibly important these days to be an "author-preneur."

I work now with the Midwest Writers Workshop, a great conference in Muncie, Indiana. Last year, I was on the faculty and over a two-day period, I taught short sessions on craft, but because I was scheduled against sessions on HOW TO GET AN AGENT and HOW TO GET A MILLION TWITTER FOLLOWERS (I'm exaggerating a little), I spoke to a very small number of people. To address this problem, this summer, we created an entire block of nothing but craft sessions to emphasize how much the conferences values good writing AND learning the business.

The point is: Faced with the choice between an opportunity to learn how to be a successful, popular writer vs. an opportunity to learn how to be good, highly skilled writer, most people will choose the former. Do MFA programs really want to present even more opportunities for young writers to obsess about SEO or their Klout score?

If writing is a business, should we teach them how to stay in business?

But on the other hand (can you tell how conflicted I am about this subject?!) given the state of the academic job market, how can we not offer some real-world survival skills to the hundreds of students we loose upon the world each year?

This is a very serious question.

And isn't this at least part of the reason to offer instruction to fiction writers in how to write a novel?

And while we're at it, how about teaching them how to adapt the novel into a screenplay or teleplay, as writers like Benjamin Percy and Dean Bakopoulos and many others have done?

In a Huffington Post article last year, Brian Joseph Davis suggested "diversifying with more commercial applications of creative writing," which would "balance practical skills with the no less important art of completely impractical, clever and beautifully unmarketable literary fiction writing."

In a Huffington Post article last year, Brian Joseph Davis suggested "diversifying with more commercial applications of creative writing," which would "balance practical skills with the no less important art of completely impractical, clever and beautifully unmarketable literary fiction writing."

I'd suggest including screenwriting, as some programs already do, or adding more new media courses. How about courses that prepare MFA grads for ghostwriting an unauthorized Hugh Laurie biography, one that earns them enough money to pay rent for a year so they can work on a novel?

As a former MFA faculty member, I'm interested in anything that gives MFA students an opportunity to lead literary lives–however they choose to lead them. At the same time, I want to pose this question: Isn't it hard enough to teach someone to read and write well in 2 or 3 years? Are MFA programs responsible for equipping graduates for all possible professional outcomes?

I don't know the answer to this question, mind you.

This will make me sound like a fuddy duddy, but I have to say it: as mentioned above, my MFA program didn't professionalize me about the publishing world, and yet, here I am anyway. Everything I thought "being a writer" would mean in 1995 is completely different today, and I've adjusted.

It's not that I think my students should "learn things the hard way" just because I did. Rather, I think the way is always hard, no matter what you do or how you prepare someone.

Meaningful anecdote

Once, I was on a committee charged with reading alumni surveys. All undergrad English majors. One guy wrote to say he was very disappointed in his major because at his first high school teaching job, he was asked to teach The Sun Also Rises, "and you never made me read that book!" To which we responded, "Did you read any Hemingway? Did you read any Lost Generation writers? Did we teach you how to read a book critically, how to research things you don't already know? Surely we did. Surely we can't prepare you for the exact circumstance each graduate will face. We hope we taught you the most important thing: how to teach yourself."

If writing is a business, so is creative writing instruction

In the years ahead, MFA programs must decide whether or not to respond to these demands for more professionalization, more real-world, practical skills. Because they will start losing students: to the Grub Street Novel Incubator, to low-res programs, to courses (IRL and online) offered by independent centers and literary magazines and the distance-education arms of major universities, to the growing number of writer conferences, to privately run writing groups, to critique sessions offered by writers.

As creative-writing instruction goes, MFA programs used to be the only game in town. Now, they aren't. If a young writer knows exactly what she wants and an MFA program can't provide that, she will look elsewhere for those opportunities–and believe me, she will find someone ready to give her exactly what she wants.

What about you? What do you think? I'd really like to know, because as you can tell, I'm awfully conflicted on this issue. I'd also like to expand these thoughts and publish them. What other topics should I explore?