How A Rhinocerous Named Max Altered My Perceptions

Rhinos have always appeared to me to be elusive, other-worldly beings. Most people, including myself, who have seen the rare rhinoceros don’t usually talk about them with the same emotional furor used to speak about elephants, big cats or gorillas.

The rhino’s pre-historic coats of armor don’t inspire warm and cuddly feelings.

And, although I was always elated to see one on safari, the emotions were ephemeral, a result of understanding how rare the sighting was.

Rhinos and leopards are the rarest of the Big 5 to spot on safari

Rhinos and leopards are the rarest of the Big 5 to spot on safariAll of that changed when I met Max.

After reading Daphne Sheldrick’s book I visited her elephant orphanage in Kenya. Although the main attraction here were the orphaned baby elephants, at the end of the visit I noticed an enclosure separated from the elephants stalls.

Inside was an intimidating bulk of animal – a one-and-a-half-ton rhinoceros. Sensing me, Max, the blind orphaned rhino walked straight towards me.

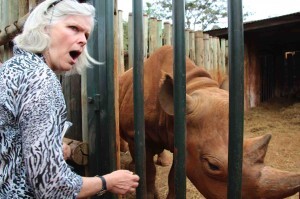

PETTING A RHINOCEROUSTwo lethal looking horns projected from the front of his head as he turned his body sideways against the steel bars separating me from him.

I reached my hand through the slat. Doubting he could sense my touch through rhino skin that felt dry, gritty, like sandpaper, I began to scratch.

His head sunk incrementally lower and lower toward the ground as his muscles gave way to my massage. And he closed his eyes.

I rubbed around his face, ears, and cheeks. And then he maneuvered his belly towards my hand. Did he really want me to rub his belly?

blind Max asking to be rubbed. photo: Barbara Calvo

blind Max asking to be rubbed. photo: Barbara CalvoYes, he did.

And then I heard it: A long low sigh– a sound that seemed to come from somewhere deep inside.

Was he crying?

What is Max saying? Photo: Barbara Calvo

What is Max saying? Photo: Barbara CalvoFound blind and motherless, Maxwell was brought to the elephant orphanage at the start of 2007. I kept stroking him, and then I started to cry. I wept for my lack of understanding of this magnificent animal, and for all the pain inflicted on his species.

POACHING CRISIS

The news is full of rhino poaching stories. There are an estimated 1,000 rhinos killed annually, and an estimated 30,000 left in the wild.

The poachings have a mafia-like level of sophistication, and the prices fetched ($133 per gram of powdered horn) equal profits rivaled in drug and sex trafficking.

The rhino’s horns are brutally hacked off their faces (fatally wounding the animals) and then shipped to Laos, China, and Vietnam where the horns are used as high-level gifts by governmental officials and other wealthy business people.

Credit: World Rhino Day web site

Credit: World Rhino Day web site

The crazy thing is, the horns are made of keratin, the same substance of our finger and toenails.

Good News for RhinoOn all my Kenya safari itineraries I include the Lewa Wildlife Conservancy. The place started as a rhino sanctuary and has become a model of conservation worldwide. Working with the local communities there has resulted been zero poaching in the area for many years.

When I told Max’s caretakers at the Sheldrick orphanage that Max seemed to be crying while I caressed him, they replied, “No, no, he wasn’t crying. He was happy,” they said.

“He loves to be touched and he especially loves to be tickled.”

Rhinos love to be tickled. And why wouldn’t they?

****

WHAT YOU CAN DO:

Help save rhino. Donate to Saving Wild and we will send your money to the best organizations helping to save the rhino from extinction. To make a donation, go here.

The post appeared first on Saving Wild.