What Does it Mean to be Domesticated?

If you have been reading along for the last 1300 or so weekly essays of mine, you know sometimes I get testy about words. I decry those insensitive people who “desensitize” horses. I have no respect for those who hijacked the word “respect” to justify disrespecting horses. Both of those word abductions have sent me where I am currently, deep in a rabbit hole about whether horses are truly domesticated. Rabbits, by the way, are categorized as both wild and domestic. I notice when rabbits get out, most turn feral pretty quickly. The drama is short-lived because rabbits are prey animals with fragile necks and usually get eaten before they can raise a flag and claim independence. But were rabbits really tame in the first place? It’s pretty easy to catch wild baby rabbits because they play dead when they’re afraid. Is playing dead the same as being domesticated?

Most dictionaries say a domestic animal is defined as “an animal, as the horse or cat, that has been tamed and kept by humans as a work animal, food source, or pet…” And I have a problem. Are cats domesticated? Mine still hunt moths and mice, splatter-splat. It seems a pretty shallow definition to call a cat who lets you live in her house domesticated. Doesn’t that make the human the domesticated one if we’re talking cats? They train us to be their work animal. We feed them at the crap of dawn, to clean up after them, and the dogs will be the first to tell you cats are wild and unpredictable alien creatures who cannot be trusted, no, not even a minute. “Bark. Barkity-bark.”

Wait! Then the dictionary definition of domestication continues, “…especially a member of those species that have, through selective breeding, become notably different from their wild ancestors.”

Okay then, are dogs domesticated? The chart says yes, but I have one that looks like a short hoagie-shaped fox who’s never been reliably housebroken, leaving his signature like a respectable indoor wild dog. Wolves and Pomeranians have good hair in common, but every time I watch a sled dog team, I think no way, they’re not lapdogs. I got the chance to go into an acre-sized natural kennel with a large pack of husky sled dogs. I sat with my hands in my lap, watching their calming signals while they crept closer and checked me out. Surrounded as they carefully sniffed me, I was definitely the blushing awestruck domestic one that day. Sure, lots of dogs have been sitting on our laps eating cheese for hundreds of years but I’m not sure if we domesticated them or our furniture did. I confess, at a certain age, a dog can get me to drive him to a fast-food drive-thru for a burger. It’s usually on the last trip to the vet. Generations of dogs have taught me how to behave and made me their pet. Surviving them is my greatest human accomplishment.

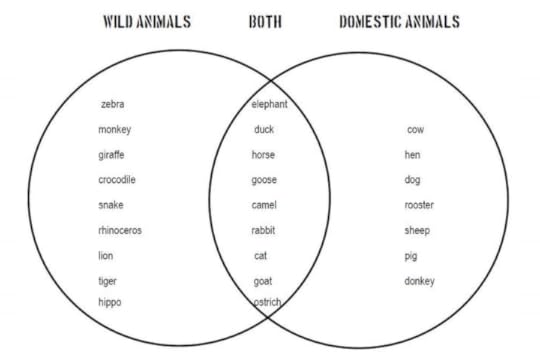

I found this diagram online. What I like is that it allows for a gray area between wild and domestic.

From the bottom of my rabbit hole, I ask in a loud, somewhat sarcastic voice, how are monkeys wild? They wear suits and smoke cigarettes; they look like your uncle Fred, down to the nose-picking. Who thinks sheep are domestic. Okay, I still hold a grudge against a Suffolk ram who broke my nose when I was five but my friend’s herd has a better recall than your dog. Maybe sheep are domesticated, but the snakes I see inside don’t look wild, so much as long lanky Zen masters who tie themselves in yoga knots and fast between feast days. Do they meditate on mice?

They are easier to catch, but does domesticating an animal improve them? What is lost? Yorkshire terriers were half-wild farm dogs who chased rodents all day before we turned them into purse dogs.

That pesky definition again: A domestic animal is defined as “an animal, as the horse or cat, that has been tamed and kept by humans as a work animal, food source, or pet, especially a member of those species that have, through selective breeding, become notably different from their wild ancestors.”

Of course, it’s horses that I care about; that I make no bad jokes about. Most definitions leave no gray area, horses are domestic animals. That humans changed them centuries ago from instinct-driven prey animals to beasts of burden. And we’ve selectively bred them, some to pull heavy loads and some small enough to fit into coal mines.

I’ve worked with wild horses: Mustangs, Kaimanawas, Brumbies, and even met a herd of Przewalski’s horses who spent much more time trying to get along than get away. Technically they are feral horses, but if feral horses are not domesticated, why do they look so similar to our horses? Why do they settle into captivity so quickly, and many times, are as easy to train? Why do our domestic horses are need fences to hold them? We like to think horses volunteer by coming to the gate for a carrot. Even if the pen is acres large, a horse knows he’s captive.

We want to think that draft horses are “gentle giants” when their flight response is no less sensitive than a hot-blooded plain-speaking Arabian. We want to think ponies are children’s horses when they have no special skill and a golden-retriever-of-a-quarter-horse would be a kinder, safer option for kids.

Why do so-called domestic horses still spook, listening to the environment for fear of predators instead of our voices? Why do our horses show anxiety when we stand too close? If we’re honest, we value “tame” horses, so shut down that their eyes look dead as a baby rabbit.

It matters because we make up untrue stories. We imagine horses into stuffed toys to cool our anxiety. We talk loud to dim their intelligence. We micromanage them to sublimate their strength. We overlook uncomfortable emotions to ignore their physical pain. It’s as if the more we believe horses are domesticated, the less we have to understand their true nature. It matters because horses are not all thriving under our care. Sometimes our drive for excellence in training turns into an effort to change who horses fundamentally are.

Here is a solemn salute to the many horses, especially mares, who have refused to submit to domination, prey animals who refused to be slaves to our anger and force? They might say, “What if horses are not domesticated so much as more tolerant than other wild animals?”

Would we be more patient or respectful of horses if we saw them as “wild” animals? Domestication is a statement that we own their life. Is it worth it if we diminish their autonomy?

To understand that a horse is a horse is to respect their sensitivity, to celebrate their hyper-awareness of the environment, and to never get complacent about the simple tasks. That we never become complacent about what it means to surrender to a halter, to give a hoof to a predator. It isn’t our right. Be humbled by that.

We are the ones who must learn respect. Not with the dominant use of discipline or with aggressive neck-clinging love. We must learn old-fashioned respect. We must value their autonomy.

…

Anna Blake, Relaxed & Forward, now scheduling 2022 clinics and also, barn visits. Information here.

Want more? Become a “Barnie.” Subscribe to our online training group with training videos, interactive sharing, audio blogs, live chats with Anna, and join the most supportive group of like-minded horsepeople anywhere.

Anna teaches ongoing courses like Calming Signals, Affirmative Training, and more at The Barn School, as well as virtual clinics and our infamous Happy Hour. Everyone’s welcome.

Visit annablake.com to find archived blogs, purchase signed books, schedule a live consultation, subscribe for email delivery of this blog, or ask a question about the art and science of working with horses.

Affirmative training is the fine art of saying yes.

The post What Does it Mean to be Domesticated? appeared first on Anna Blake.