Magic Mirror

In October of 2021, a small black mirror added a new chapter to its fascinating story. It’s slightly over 7” in diameter, concave, made from black obsidian (volcanic glass) and polished on both sides. A flange at the top is pierced by a single hole, allowing the mirror to be suspended by a cord.

Mostly we think of mirrors as useful items in our everyday life. They help us check whether we have spinach in our teeth or whether a car is coming up alongside us. They work in cameras, telescopes, lighthouses. They help dentists and surgeons. These are working mirrors.

But the small black mirror that made the news was a magic mirror. We don’t hear about them much, except in stories like “Snow White,” “Through the Looking Glass,” (illustration by John Tenniel shown below) and “Beauty and the Beast,” or the Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter series. Those are powerful, enchanted mirrors.

A 2021 study published in the journal Antiquity showed that the obsidian “spirit mirror” used by Queen Elizabeth I’s court scientist/astrologer/seer, John Dee, actually had Aztec origins. Researchers had suspected as much, since the mirror was said to belong to Montezuma, but the study proved its source, identifying the particular combination of elements found in the mirror as coming from Pachuca, just northeast of Mexico City.

In 1521, Spanish forces under Hernan Cortes conquered Tenochtitlan (later site of Mexico City). They captured and killed Montezuma, burned the city, and shipped plundered treasures, including gold, silver, jewels, and ceramics back to Spain. Among these treasures were what were considered “curiosities,” exotic bits and pieces that the wealthy could display in curio cabinets. While the fancy ceramics and jewelry found ready homes, the little mirror was passed from one estate to another.

John Dee

John DeeEventually, John Dee acquired it and added it to his collection of magical objects, using it for “scrying,” looking at the surface of the mirror in an attempt to find visions of the future or answers to questions. Divination was a tradition in the royal court. Henry VII and Henry VIII had seers. Dee started out advising Mary, Queen of Scots, Elizabeth’s half-sister and rival. When Mary died (by execution), he went on to advise the new Queen, quite an impressive feat of political juggling.

Queen Elizabeth I, like many others, felt there was little difference between magic and science. Certainly, many of the advancements of the age must have seemed like magic. The refracting telescope showed Galileo Galilei the skies. Anton Van Leeuwenhoek saw and described bacteria. Wilhelm Leibniz invented a calculating machine. Thomas Savery invented a steam pump. Suddenly the world became more complicated and the stakes higher. Elizabeth faced threats from both Spain and the Catholics at home who followed her half-sister, Mary. Religious/political wars raged. She needed whatever help science/magic could offer.

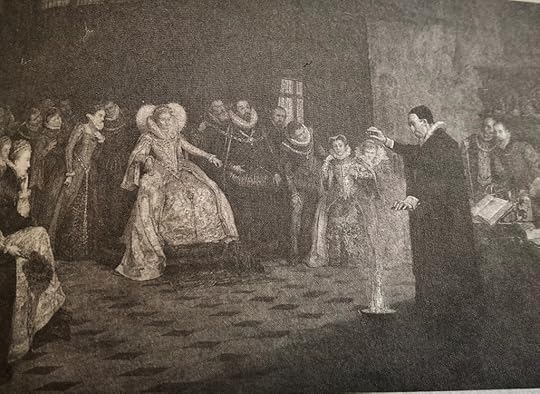

Queen Elizabeth and court with John Dee

Queen Elizabeth and court with John DeeThe drawing in the photo shows Queen Elizabeth in a group watching John Dee “combine elements.”

Elizabeth looked to Dee for advice on science, technology, and medicine, as well as matters of the spirit. He became a trusted advisor. However, his interest in the occult arts, particularly speaking to ghosts and angels, eventually did him in. After Elizabeth I died, James, son of Mary, Queen of Scots, became King. He hated anything smacking of magic. Dee was excluded from the court and left to find whatever work he could. He died impoverished, even after selling off his collection of ancient books and occult items. Some scientists are now trying to emphasize his contributions to mathematics and astronomy. But he’s mostly remembered as Elizabeth’s seer, who, along with his cohort, Edward Kelley, carried on seances and scrying sessions.

Two interesting questions arise about the mirror:

Why did it have such a dark, dangerous reputation? Notes stored with Dee’s mirror refer to it as “The Devil’s Looking Glass.” When I was reading reviews of one mirror on-line, I came across several warnings about the mirror’s ability to suck one’s soul into Darkness.

(Despite the warnings, I bought a small obsidian mirror and found the images fascinating and somewhat mysterious. Pictured is a model of a knight reflected in my mirror. So far, I’ve not felt my soul being sucked into Darkness.)

How much did Dee know about the mirror’s history or use in pre-Conquest Mesoamerican culture? Was he trying to continue Aztec customs or did he see the mirror as simply an exotic accoutrement of a distant civilization, something useful in a show of magical power?Mirrors in Mesoamerica

Mirrors have a very long history in what is today called Mexico, often found in Olmec, Maya, and Teotihuacan archaeological sites.(See map) The oldest mirrors discovered predate the Olmec civilization, making them close to 5,000 years old. Many are quite sophisticated, showing extensive knowledge of materials, grinding techniques, and light refraction. But over the centuries, their use and meaning seems to have changed.

Olmecs (2500 – 400 BCE)

Olmec sculptures and burials show both men and women wearing small round mirrors, usually on the chest or in a headdress. The statue in the photo above shows a woman with a chest mirror. Several smaller figurines of women with chest mirrors are on display at the Museo de Antropologia in Mexico City.

In addition to being a striking piece of elite jewelry, the mirror must have been a marker of exceptional power/energy. They often appear in headdresses of living leaders. In burials, round mirrors were placed on the dead person’s head, chest, sometimes back and groin.

While a flat mirror would have been striking, a concave mirror (one that curves inward), which is more time-consuming to make, is found more often. Why? Did these people see them as magic?

Here’s one possibility: A concave mirror is a fire starter. For example: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CupTM0R1DME

Mirrors were often associated with the sun, perhaps because of this fire-starting ability. It would have been particularly impressive if the fire source was the mirror in the headdress.

In addition, a mirror can change the direction of a light source. If you shine a flashlight at a mirror, it will redirect the light depending on how you hold both items. If ancient people were trying to see around a dark corner, a mirror and a torch would be a big help.

It can also play games with perception. A concave mirror can enlarge, shrink, or invert an image. If you look at your reflection in a spoon that’s close up, your reflection looks normal, but if you back away, your reflection looks upside down. Here’s a fun explanation: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N6n0FAZ_6N8

If otherworld entities – ancestors and supernaturals — were thought to be on the far side of the mirror, the mirror would become a portal to a world that could be seen but not entered.

Take the sculpture of the ruler pictured. He has a mirror in his headdress and holds a larger mirror. With two mirrors, he could create multiple images that seem to recede into infinity.

If he lit a bit of oil in a pot in front of the mirror on his headdress, would he become a human light, a messenger of the sun? A light in the darkness, a “smoking mirror”?

Maya City States (1500 BCE to 200 CE)

The Maya, like the Olmecs, valued mirrors. Hundreds of mirrors have been found in Maya sites. In burials, they were placed near the head, chest, back, groin and feet. The “smoking mirror” image became part of the creator god named Huracan/Hurricane, the Heart of Sky.

“There is also the Heart of Sky. This is the name of the god, as it is spoken. And then came his word, he came here to the Sovereign Plumed Serpent, here in the blackness, in the early dawn… They agreed with each other, they joined their words, their thoughts. Then it was clear, then they reached accord in the light, and then humanity was clear, when they conceived the growth, the generation of trees, of bushes, and the growth of life, of humankind, in the blackness, all because of the Heart of Sky, named Hurricane….” – Quote and illustration from the Popol Vuh, translated by Dennis Tedlock

In this drawing by Karl Taube taken from a ceramic vase, the figure of Heart of Sky is shown with the obsidian mirror in his forehead and the swirls of smoke and flame coming out of it.

The god K’awil, which seems related, is often pictured with an obsidian mirror on his forehead with an axe stuck in it. Typically, he has one serpent leg. The scepter bearing his image is often associated with kings.

Clearly, the obsidian mirror in these cases is associated with great power, the generative power of the gods at the moment of creation. When it is incorporated into a king’s scepter, it becomes a divine justification for his rule.

Teotihuacan (200 BCE – 600 CE)

In the great empire of central Mexico, mirrors were associated with faces, especially eyes. Like the people before them, elite Teotihuacanos wore mirrors as part of their costume, often in headdresses, on belts, and on the chest. Some were hand-held. They were associated with fire and the sun. When they were used for divination, they were considered caves or portals to another world. Sometimes serpents were shown emerging from the mirrors.

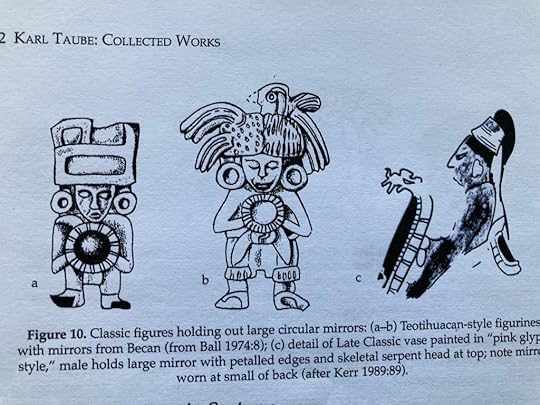

Toltec warrior with back mirror with face, Teotihuacan ruler with mirrors, drawings of figures holding mirrors

Toltec warrior with back mirror with face, Teotihuacan ruler with mirrors, drawings of figures holding mirrorsMirrors were also part of battle gear, worn on the chest and on the back, as well as used in shields. It’s interesting to speculate on their purpose. Were the mirrors meant to stun the enemy? Were they worn as protection against supernatural forces or a way to call on their aid? Did the troops have specific maneuvers with the mirror shields that would blind the enemy?

Mirrors are more about military power here. Together, they would have made an intimidating display of might.

Aztec Empire (1200 CE – 1521 CE)

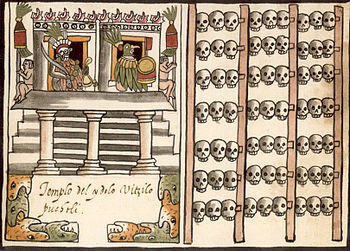

skull rack, Tezcatlipoca, and mask

skull rack, Tezcatlipoca, and maskThe Aztec deity Tezcatlipoca, “Smoking Mirror,” is the personification of a black obsidian mirror. In paintings, he has black and yellow stripes across his face. One of his feet is usually a mirror. In the image shown, you can see the mirror foot and another mirror in his headdress, with wisps of smoke emerging from each. He is a powerful, dangerous deity. He’s associated with night, hurricanes, hostility, sorcery, temptation, and war. In Aztec mythology, he is famous for tricking his brother and rival, Quetzalcoatl, the Feathered Serpent, into getting drunk and sleeping with his sister, which so shamed him that he disappeared beyond the eastern horizon.

In many ways, Tezcatlipoca is the later, darker version of the “smoking mirror” figures we’ve seen developing over the course of Mesoamerican history. The similarities with K’awil and Huracan are hard to miss. They too were powerful creator gods marked by their use of black obsidian mirrors. But Tezcatlipoca, the Smoking Mirror, was a figure of violent extremes. His spirit animal, the jaguar, was the embodiment of the sun at night. His names included “Night Wind” and “Enemy of Both Sides.” The turquoise mask of Tezcatlipoca (shown), from the British Museum collection, is terrifying. It features a gaping mouth with ragged teeth and strange mirror eyes. It suits a deity to whom thousands were sacrificed.

The mirrors here seem very different from the statue of the Olmec woman with the mirror on her chest.

Montezuma was said to have foreseen his downfall in an obsidian mirror. It was a vision of warriors mounted on deer. In a different version of the story, he saw the image of a brown bird with a mirror on its forehead which showed the night sky. When he looked again, he saw many warriors attacking. These stories probably added to the sense of the mirror being the harbinger of doom.

What did John Dee know about the history of the obsidian mirror in Mesoamerica? Hard to guess. He may have heard some of the stories about Montezuma and his dark visions of defeat. Maybe he read something about Tezcatlipoca and the staggering number of blood sacrifices made to him, but Dee probably knew almost nothing of the earlier history of the obsidian mirror in Mexico. Most of the handwritten records of the Maya and Aztecs were destroyed by the conquerors, the monuments torn down, the people converted, by force if necessary, to the new religion, the old gods replaced with new ones. The bits and pieces left behind turned into legend and rumor.

And so, separated from the culture that gave it meaning, the polished obsidian mirror became only a curiosity, part of a magic show meant to entertain the Queen, and a novelty for the people who glance at it today in its glass case in the British Museum. Interestingly, though, even after all these years it retains a touch of its dark magic, enough to make people post warnings online about its power.

Sources and interesting reading:

Cartwright, Mark, “Tezcatlipoca,” World History Encyclopedia, 14 August 2013, https://www.worldhistory.org/Tezcatlipoca/

Fields, Virginia M and Dorie Reents-Budet, Lords of Creation: The Origin of Sacred Maya Kingship. Catalog of the Los Angeles County Museum exhibition, first published by Scala, London, 2005, source of images of K’awil, the seated ruled with mirror headdress and divination mirror, and the seated female figure with mirror on her chest

Foster, Lynn V. Handbook to Life in the Ancient Maya World. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Gosden, Chris, Magic: A History: from Alchemy to Witchcraft, from the Ice Age to The Present. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020.

Maestri, Nicoletta, “Tezcatlipoca: Aztec God of Night and Smoking Mirrors,” 03 July 2019, Thought Co. https://www.thoughtco.com/tezcatlipoca-aztec-god-of-night-172964

“magical mirror; mirror case,” British Museum description of John Dee’s mirror and case, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/H_1966-1001-1

“Mayan Gods: Huracan,” Yucatan Living, 22 June 2017, https://yucantanliving.com/culture/this-is-the-story-of-the-huracan

Miller, Mary and Simon Martin, Courtly Art of the Ancient Maya, catalog of the exhibition at the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, Kathleen Berrin, Curator, Thames and Hudson, 2004

“Mirrors in Mesoamerican culture,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MIrrors_in_Mesoamerican_culture

“Reflection,” Ology, American Museum of Natural History, concave and convex, https://www.amnh.org/explore/ology/physics/see-the-light2/reflection

Schele, Linda and Mary Miller, The Blood of Kings: Dynasty and Ritual in Maya Art, first published by George Braziller, Inc, in association with the Kimbell Art Museum, 1986.

“Scrying,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scrying

Stone, Andrea and Marc Zender, Reading Maya Art: A Hieroglyphic Guide to Ancient Maya Painting and Sculpture. London: Thames and Hudson, 2011. Source of mirror glyph and example

Strickland, Ashley, “Obsidian ‘spirit mirror’ used by Elizabeth I’s adviser has Aztec origins,” CNN, 6 October 2021, https://www.cnn.com/2021/10/06/world/obsidian-mirror-aztecs-queen-elizabeth-i-scn.index.html

Taube, Karl, “Iconography of mirrors at Teotihuacan,” [1992] 2018 In Studies in Ancient Mesoamerican Art and Architecture: Selected Works by Karl Andreas Taube, pp. 204 – 225. Precolumbia Mesoweb Press, San Francisco. Electronic version available: http://www.mesoweb.com/publications/Works

Tedlock, Dennis, translator, Popol Vuh: The Definitive Edition of the Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life and the Glories of Gods and Kings. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995.

Vit, Josef and Michael A. Rappengluck, “Looking through a telescope with an obsidian mirror. Could specialists of ancient cultures have been able to view the night sky using such an instrument?” Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry, Vol 16, no 4 (2016) Open access.

Weisberger, Mindy, “’Spirit mirror’ used by 16th century occultist John Dee came from the Aztec Empire,” 07 October 2021, Live Science, https://www.livescience.com/john-dee-spirit-mirror-aztec source of image of John Dee and the mirror