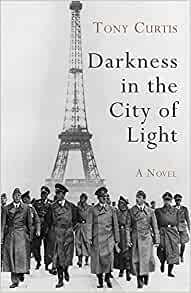

Review of Darkness in the City of Light by Tony Curtis, pub. Seren 2021

“Perhaps we will come through this present madness and the cafés, the Seine, the Sorbonne and the Louvre will be here as always and the city will be reclaimed by us again.”

The first thing to note about this novel is that the protagonist is not really any one person but rather the city of Paris itself at a certain time in its history; in this it is in the tradition of novels like Dos Passos’s Manhattan Transfer. It also resembles that novel in using several different narrative methods: diaries, letters, court reports, poems, newspaper articles, official posters, even photographs.

Some of the various voices will be familiar from other contexts: Picasso, keeping his head down in his apartment and painting carefully noncommittal still-lifes, Max Jacob, appealing to his friends for help that doesn’t come, Albert Camus, editing a Resistance paper, Ernst Jünger, a civilised man trying, unforgivably, to close his eyes and ears to barbarity, Hemingway, swaggering drunkenly through the Liberation unaware of how those who actually accomplished it are laughing at him behind his back. Others don’t speak but appear in memorable vignettes, like Fred Astaire tap-dancing down the Place Vendôme. The person the back cover concentrates on is the serial killer Maurice Petiot, who preyed on people wanting to escape the Nazis and murdered them for their possessions. But actually he does not dominate most of the novel any more than the others, which is just as well because, like many intrinsically evil people, he’s actually a bit of a bore, banal and predictable. I don’t doubt this portrayal of him is accurate enough, I just didn’t find him as interesting to read about as more equivocal, many-sided characters like Jünger and Picasso.

Their voices, and indeed the voices in general, are very well differentiated and convincing; the only conversation that didn’t quite ring true for me was a brief one between two GIs, “Jimmy” and “Sid”. But the character they are all working to build up is that of the city itself. This, as one would expect, is seldom black and white; it is clear, for instance, that some of the Resistance fighters, after the Liberation, behaved as thuggishly as the Milice did during the war. And some of the erstwhile conquerors, shorn of their authority, look, even to the recently oppressed, like what they are:

“And at the tail of this long rat procession, a few stragglers, some limping, some unsteady, with vacant faces and making their way through their own dream. And then scattered among them some so young that they seemed like schoolboys. Some with their hands behind their heads. One kid with his head slumped down against the back of the fellow in front, not looking or taking anything in. What was he thinking of – his mother, his home? What was he remembering? A few days ago, I thought, I could have slit his throat.”

Perhaps the strangest thing, though utterly convincing, is the consciousness that all this will be absorbed into the city’s history, like so much before:

“One morning when I went out in search of food within a short walk of our apartement I saw young boys and old men fishing in the Seine in the sunshine as if nothing was amiss. Some other boys dived from the bank and swam. This could be a painting by Seurat or Monet.”

This is an unusually structured novel with a lot of intrinsic interest, though for me, it does not in fact centre around Petiot, but around Paris.