Twinkle, twinkle, or stars and sparks

Nothing is known about the origin of the phrase Milky Way. The myths usually cited to explain it are late, that is, not recorded in Classical Greek. (The idea of milk is also reflected in the word galaxy: Greek gála “milk”; hence possibly Galatea, if her name means “ivory-white.” By contrast, the origin of the word star is not hopelessly obscure, which is good, because stars and obscurity have little in common. For example, the Slavic word for “star” (Russian zveda, and so forth) which, as we can see, is quite different from the English one, has been reconstructed as “shining; glistening.”

What then is the etymology of star (Old Engl. steorra, Dutch ster/star, German Stern, Old Norse stjarna)? Similar-sounding cognates occur all over the map, but I’ll mention only two, for the reasons that will become clear later: Latin stella and Greek aster (familiar to English speakers from stellar, constellation, astral, and asteroid). The noun star is obviously Indo-European, but the Semitic words are strikingly similar and are known to many people from the names of the deities Ishtar and Astarte, the counterparts of Venus. Some scholars maintain that the Indo-European word for “star” is a borrowing from Semitic. I have doubts about this conclusion and will return to it at the end of the blog post. Our predictable question is the same as always: “What was the connection between the meaning of the ancient word designating “star” and the phonetic shape of that word?”

Galatea with Rodin as Pygmalion.

Galatea with Rodin as Pygmalion.(By Auguste Rodin via The Met)

Below, I’ll report a hypothesis that few people remember. There was a scholar named Max Müller (1823-1900). At one time, every educated person knew his and his father’s name, for Wilhelm Müller (the father) is a poet to whose words Franz Schubert wrote many of his best songs. Max Müller was a mythologist and a great expert in Indian religion and Sanskrit. According to him, the oldest Aryan ancestors thought of stars as scatterers of light. The idea of scattering presumably passed on into the articulate word by which ancient people called a star. Müller coined the term clamor concomitant. He explained that, when, for example, people cut down a tree and saw splinters scattered on the ground, they would have accompanied the act of cutting with some cry or noise. Hence, allegedly, a verb like cut appeared, and similar was, according to Müller, the origin of all first words, including star, for stars are scatterers of light. In a way, he likened the human being to a bell: you strike a bell and some sound will come as a result.

Max Müller’s opponents called this rather bizarre approach to etymology the ding-dong theory. But, if instead of referring to the forever hidden impulses we say that some words evoke certain images and recognize the role of sound symbolism, we may ask ourselves: “Does the complex star, Indo-European or Semitic, conjure up any image in us?” Many words do: think of slobber, fluent, creak, and their likes. It is so fortunate that shrapnel was invented by General Henry Shrapnel, rather than by someone called Melissa Sweet or Lyle Darling: you pronounce shrapnel and guess its purpose. Earnest, as Gwendolen, a character in Oscar Wilde’s play, said, produces vibrations, while Jack does not. At first blush, star produces no vibrations.

Let us now turn to a short 2002 paper by the Russian scholar Mikhail Nikolaevich Bogoliubov (or Bogolyubov). But first I must cite Russian iskra “spark” (some historians my know that Iskra was the name of the newspaper founded by Lenin; its epigraph promised that a spark would start a fire; it did, it did) and Polish jaskry ~ Russian iasnyi “bright, scintillating.” A few other related words in Slavic and Baltic have the same meanings. Persian axtar “spark” and axgar “a live coal” are reminiscent of Greek aktís “ray; sheen” and Sanskrit aktú “light” (noun). The root is ak-.

These are Ishtar and Astarte, our great astral goddesses.

These are Ishtar and Astarte, our great astral goddesses.(Left: Ishtar on an Akkadian seal, Sailko. Right: Figure of Astarte-Isis, Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

According to Bogoliubov’s reconstruction, two roots competed in Indo-European: star– “star” and skar– “live coal” (remember Russian iskra!). Some Sanskrit and Greek forms show that initial s was unstable. Homeric teírea “constellations” (no initial s) is not isolated and has counterparts in Sanskrit. This situation resembles the case of the so-called movable s (s-mobile), to which I keep referring with depressing regularity. Now comes Bogoliubov’s main point. The instability of initial s in star– was allegedly obvious to the speakers of Indo-European, and they produced a blend, that is, they combined two roots by substituting ak– for s- in star. Initial a in Greek astér is then also a stub of another word for “burn.” The idea that this a- is some sort of prefix is old, but Bogoliubov gave an ingenious explanation of its existence and denied it the status of a prefix.

The origin of Russian iskra “spark” and its cognates has been discussed multiple times. I can only add that the etymology of words meaning “spark” is usually problematic (look up spunk and funk in English dictionaries and compare the latter with German Funke “spark”). According to what we have seen, two roots—str and spr—were involved in coining the recorded words for stars and sparks. The essence of sparks is revealed by the verb sparkle. Any open source of open fire strews sparks. It may therefore be profitable to accept an affinity between stars and sparks, with str and spr being sound-imitative or sound-symbolic complexes. Sparks resemble stars and are often associated because both spread fire and light. If the foregoing discussion has any weight, Max Müller will be partly vindicated, not because once upon a time a very ancient speaker of some Indo-European dialect looked at the stars and—ding-dong—the word star appeared. Rather, the spectacle of scattered, strewing light resulted in the coining of a sound-symbolic word. Once we agree that stars and sparks form a close alliance, this conclusion will appear quite reasonable.

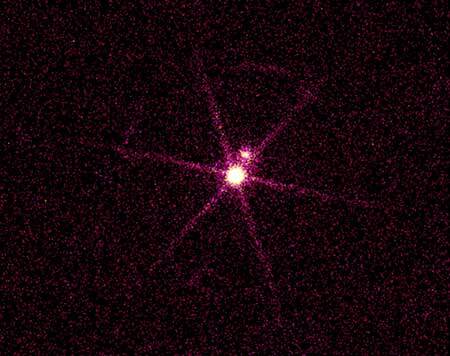

Sirius, the brightest and hottest star in the galaxy. Stay away!

Sirius, the brightest and hottest star in the galaxy. Stay away!(Image: Sirius A and B: A Double Star System in Canis Major, NASA)

Star has also been associated with Latin sternere “to spread out,” but this etymology would fit the entire Milky Way rather than a single star. The oldest form of the Indo-European word for “star” seems to have begun with the guttural sound: h or some other consonant like it. The same is true of the Semitic lookalikes. The function of this laryngeal has never been explained (an emphatic sound?). If the tie between star and words like Russian iskra “spark” can be accepted, star will remain a word of Indo-European origin, but the problem of the Semitic lookalikes will not go away. Are we dealing with a migratory word, or did the Semites borrow the word from their Indo-European neighbors?

Some minor problems needn’t be discussed here (for example, the length of rr, that is, long r in Old Engl. steorre and the origin of final n in German Stern “star”), but we can possibly agree that Latin stella goes back to ster-la. In recent years, only the phonetic structure of the many Indo-European words for “star” has been discussed in some detail. Bogoliubov’s short contribution is an exception: it throws a new light (!) on the old problem. If someone agreed to translate the note into English and publish it in some visible journal, Bogoliubov’s idea might become available to the entire constellation of modern etymologists.

The next blog post in the Oxford Etymologist series will be published on Wednesday 5 January 2022. The Oxford Etymologist wishes everybody a safe New Year!

Feature image by Graham Holtshausen via Unsplash

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers