False Profits: The Ponzi scheme and spiritual impoverishment

False Profits | John B. Buescher | Catholic World Report

A cautionary history of the Ponzi scheme, and what it tells us about our spiritual impoverishment.

I. Payoff at Infinity

In 1933, at the height of the worldwide economic depression, G. K. Chesterton wrote, "The modern world began by Bentham writing the Defense of Usury." He was referring to Jeremy Bentham's 1787 essay rejecting any state-imposed limit on interest rates. Bentham's contemporary, Adam Smith, the father of free markets, nevertheless recommended such a limit, fearing that without it, profligates and projectors, which is to say, speculators, would suck up more and more money into riskier and riskier future "projections."

Bentham's paean to credit had more than a whiff of utopia about it. The idea was to put behind us the inhibitions we had about usury so that capital could be liberated to bloweth where it listeth, to be invested in innovation, in change, and so, in effect, in the future. Mere individual charity would be replaced by a centrally directed but abstract "Philanthropy." Without limits on interest rates, the future itself could be liberated from the constraints of the past and the present. Through investment, the future could be gathered up and harvested now. It was a financial form of a secular messianism, through which mankind would initiate a new heaven on earth, rather than waiting on Providence to do it.

Like other universal projects of the Enlightenment, it was in fact an illuminatio praecox, a Premature Enlightenment. It lacked a grasp of the richly paradoxical view of salvation that the Catholic Church has sought to keep before her: we are already saved, but the judgment is yet to come and at a time be decided by God. Christ has already redeemed us, but Christ will come again in judgment. Grace already flows to us freely, but there are also works to be done, sufferings to be borne, and consequences from our actions to be endured. Heaven is here and heaven is not yet here. We stand at the intersection of Time and Eternity, the finite and the infinite—which is to say, the Incarnation—and we cannot ignore either.

Nor can we ignore the consequences of Original Sin, which blights all man's projects with pride, until at their harvest when they are thrown into the fire. In this fallen world, what we call thievery is a sin. In the heaven of limitless credit, it is merely a transfer payment, a redistribution of wealth in the interest of egalitarian fairness.

As Bentham's predecessor Bernard de Mandeville put it in his 1705 Fable of the Hive, thievery increases the velocity of the money taken. That is a good thing for society inasmuch as the thief would then put it into circulation buying things for himself—whores, in Mandeville's provocative example, who would then pay their butchers and their grocers, who would then pay their blacksmiths, and so on. Organized thievery then would be a kind of stimulus package focused on job creation. Mandeville, it appears, neglected the fact that butchers, blacksmiths, grocers, and farmers would not stay around a place overrun by thieves, highwaymen, bounty hunters, and whores.

Bentham's financial alchemy would "immanetize the Eschaton," in Eric Voegelin's phrase, and would consist of credit transactions, traveling at limitless velocity, transmuting goods into credit, the present into the projected future, time into infinity, and, as we might say, matter into spirit. It is a Gnostic project through and through, in which each person is swept up into the Spirit. People caught up in financial schemes based on a confidence in limitless credit behave and speak very much like End Time ecstatics who have been given a "Go to Heaven Free" card.

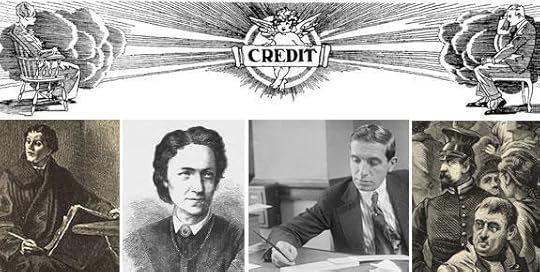

The Catholic Church has typically looked on such projects with more or less unease, as greater or lesser heresy. Is it surprising, therefore, that Catholics—Adele Spitzeder and Charles Ponzi—were responsible for history's most infamous perpetual money machines, which magically spewed out "free" wealth until they suddenly exploded?

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers