Delayed unions

On 12 January 1283, at Rhuddlan in Wales, Edward wrote to Constance of Sicily, Queen of Aragon. His letter concerned the long-delayed marriage between his eldest daughter, Eleanor, and Constance's son Alfonso.

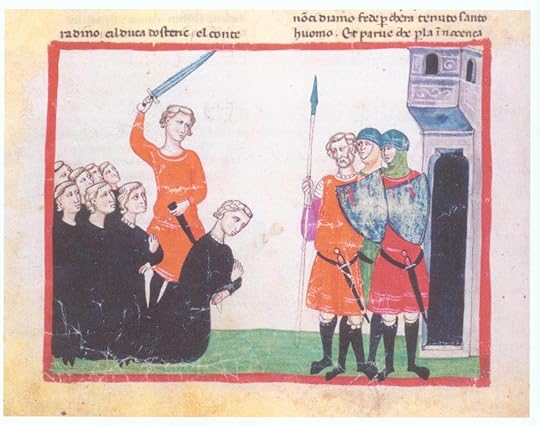

On 12 January 1283, at Rhuddlan in Wales, Edward wrote to Constance of Sicily, Queen of Aragon. His letter concerned the long-delayed marriage between his eldest daughter, Eleanor, and Constance's son Alfonso. The policy behind the marriage probably lay in the desire of the Aragonese to find allies against Charles of Anjou's aggressive domination of Sicily. Constance was the daughter of Manfred, the last Hohenstaufen ruler of Sicily, killed in the Battle of Benevento in 1266. After the capture and beheading of her 16-year old nephew, Conradin, Constance inherited a claim to the Sicilian throne.

From Edward's perspective, he welcomed an opportunity to strengthen the defence of the Aragonese-Catalan border with Gascony. This is also suggested by his attempt to secure a second union, fulfilling a similar purpose, between his eldest son Henry and the heiress to the kingdom of Navarre.

When the Aragonese match was proposed, in 1273, bride and groom were underage. In recognition of their youth – and the dangers of childhood – their first names were not included in the treaty, in case one or the other died before reaching the age of canonical consent. If the worst befell, a sibling could be wheeled out as a substitute.

As Louise Wilkinson has recently argued, Edward's relationship with the women of his extended family is largely neglected. His six daughters who reached adulthood, for instance, tend to be treated as footnotes. This is a pity, since they were required to play active roles and very far from mere ciphers. As for Eleanor and Marguerite of Provence, his mother and aunt, they were as formidable as any male politician and exercised considerable influence over him. One of the current clichés is that Eleanor of Aquitaine, Henry II's consort, was an amazing strong woman and the strongest woman there ever was, was, was, because the wonderful Wizard of Oz. In fact she was just one of many (admittedly the sheer number of Eleanors can be confusing).

Their influence is shown in the surviving correspondence. In 1282 Edward was supposed to send his daughter, now thirteen and technically of age, to Aragon. Instead she remained in England and the marriage went unconsummated. This was, as he acknowledged in a letter to his advisers, due to the influence of his wife and mother. They had allied together to persuade Edward that his daughter was still too young, even though she was one year past the age of consent for women.

It may be the two Queen Eleanors reminded Edward of their own youthful marriages at the age of twelve and thirteen. The king might have been slightly embarrassed by such recollection: when he and Eleanor of Castile were first married, they had to be quickly separated because he got her almost immediately pregnant.

In the sample letter, Eleanor's departure was again delayed. This time Edward used the Welsh war as an excuse, and told Constance he needed to deal with the Palm Sunday revolt before he could return to the matter of the wedding. The bride's journey was then impeded again by Peter III's invasion of Sicily.

Even more delays followed. The pope sought to isolate King Peter by objecting to the Anglo-Aragonese union on the grounds of consanguinity: Eleanor and her husband shared a great-great-grandfather in Count Thomas I of Savoy. Edward's requests for papal dispensation fell on deaf ears, and the match was finally dissolved by Alfonso's death in 1291.

Published on December 04, 2021 03:55

No comments have been added yet.