Worldbuilding with food

After the previous post about “easy-ish” worldbuilding, this post by Joe M. McDermott about Worldbuilding and the Labor of Food certainly seems relevant! Also, food! Who doesn’t like that as a topic, right? Plus, I already specifically use details about food in worldbuilding anyway.

The labor of food! What crops are grown and who grows them, that’s part of the labor of food. So is cooking, from the day-in-day-out grinding of grain — did you know the skeletons of ancient Egyptian women show a very typical pathology linked to the continual labor to grind grain? That’s what leaped to mind for me when I saw the title of this post. I don’t know yet what direction McDermott will take here. I’ll look in a minute.

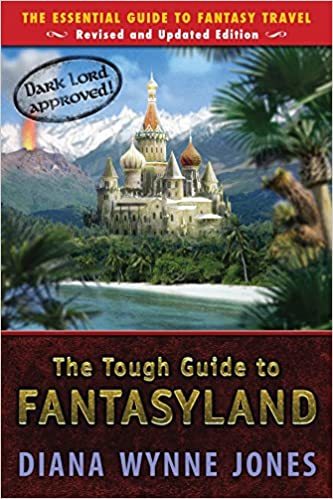

Of course, besides the labor of agriculture, there’s also the labor involved in cooking; who does the work and where, and with what variety and artistry? Remember the fun DWJ had with “stew” in The Tough Guide to Fantasyland?

Daily cooking is important, of course, but sometimes I prefer to focus on the beauty of special dishes rather than the labor involved in making, say, stew. Not just in The Floating Islands, where food is so central, but also in House of Shadows — remember the banquet scene? That was fun to write. Oh, hey, look at that, House of Shadows actually has a rating on Amazon of 4.7. I didn’t realize that until I pulled it up to get the link. I believe that must be my highest-rated book — certainly my highest rated traditionally published book. Let me just see … actually, quite a few 4.6 ratings, that’s nice to see … oh, look at this, The Sphere of the Winds actually has a star rating of 5.0!

![The Sphere of the Winds by [Rachel Neumeier]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1637742042i/32230644.jpg)

Wow, now I’m especially happy I self-published this book … was that just this past spring? How time flies! Thank you, everyone who has left a review.

Anyway, back to the topic — worldbuilding and the labor of food. Let’s see where McDermott goes with this …

I have a lot of fruit trees on my little, suburban lot. It’s a postage stamp lot, and packed in as tight as can be are six citrus trees, two pomegranates, two pears, two plums, two peaches, a jujube, three grapevines, a barbados cherry, two olive trees, a loquat, an elderberry, passionfruit vines, blackberries, raspberry…

Wow, I’m envious! I’m down to five apple trees, having given up on the stonefruits. We had tremendous trouble with brown rot starting the year when hail came in and whapped the poor peaches just as they were ripening. All the peaches rotted on the trees and brown rot sank its claws in deep and we couldn’t get rid of it no matter what we did. Huge problems every year until, as I say, we gave up and removed the trees.

We do still have elderberries and raspberries. How neat to have olive trees! Though it’s a lot easier to buy olives of whatever types appeal to you. If I could grow any fruit tree, it wouldn’t be olives. It would be a Haas avocado. If I could pick another, it’d be a mango.

McDermott has a bit more to say about the food plants at his own home. Then he segues into the actual topic:

I think about how many fantasy novels are written and read by people who don’t take even a moment to think about what the weather and landscape mean to available food. In some ways, the conspicuous absence when I read fantasy is found in the way food is grown, harvested, prepared.

This is not quite the same, but I’m thinking now about this YA series … let me see … oh, right, the series that starts with Life as We Knew It. I liked this book a lot, it was quick and fun to read — I mean, fun for a post-apocalyptic story — but I was shocked how none of the characters ever thought, “Here I am looking at imminent starvation, so maybe I should go shoot a deer before they all starve. Or I bet there are fish in that pond. Or maybe we should collect acorns; I know those are edible if you treat them somehow, might be time to try to figure that out.” It was exactly like these (rural, or rural-ish) people had no notion food could ever come from anything but a grocery store. My take: Wow, every single editor and copy editor who ever at this has got to live smack dab in the middle of NYC.

And yes, I once did gather a lot of acorns and make acorn flour. I mean, why not? I wanted to see what that was like, and there were SO MANY acorns just lying there on the deck and in the yard. I had to do something with them because some of the dogs kept wanting to eat them. To this day, Dora will drop an acorn if I point at her sternly. They are in fact somewhat toxic and I really do not want the dogs to eat them. They’re quite bitter without treatment, so I’m baffled why they want to. (I’m just letting this post ramble, as you’ve gathered.)

Back to McDermott’s post:

The amount of work that goes into a single grain of wheat, a single loaf of bread, has been lost to us. We have divided up that labor across different industries such that we see a farmhouse table in our minds populated with edible things, and we think nothing of the farm from which everything rose up to create that picturesque scene. We don’t see all the manual labor required to get the raw material of soil into seed into a form that we can eat and put on that table. …

You know who does a great job with this? LMB in the Sharing Knife series.

![Beguilement (The Sharing Knife, Book 1): Volume 1 (The Wide Green World Series) by [Lois McMaster Bujold]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1637742042i/32230645.jpg)

Because of the way Bujold focuses on normal people living normal lives (I mean, plus the occasional giant bats), we do see a lot of day-to-day life on farms and small villages. Plenty about planting and harvesting and the work involved in getting food on the table. I love the small-scale focus on daily life in this series. That’s one of the factors that makes this series so comfortable to re-read.

McDermott writes:

I have grown a bit of corn from seed and dried it and ground it up into corn flour, and saved the seeds for another year’s cornbread. I have reached into the past to try and figure out how the people who lived here for a thousand years and more managed to survive on acorns and roots and pumpkins and peppers. We talk about world-building all the time, as writers, but we do it in our heads, where we can invent whatever suits us. When I build a world in my little yard, and it is an act of world-building, of managing forces and distances, constructing ecosystems and figuring out solutions to problems I unintentionally create, I am forced to face the hard truth of building a world.

That’s nicely put.

Please Feel Free to Share:

The post Worldbuilding with food appeared first on Rachel Neumeier.