Frantic action

9 October 1297. On this day Jean de Chalon, a lord of eastern Burgundy, sends two letters to Edward I at Ghent. He informs the king that Jean and his followers have stormed the castle of Ornans and slaughtered the French garrison:

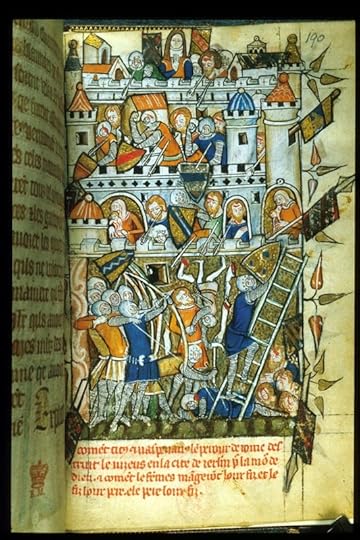

9 October 1297. On this day Jean de Chalon, a lord of eastern Burgundy, sends two letters to Edward I at Ghent. He informs the king that Jean and his followers have stormed the castle of Ornans and slaughtered the French garrison:“Most dear sire, this is to inform you, that on Tuesday, the eve of the feast of Saint Denis, myself and my companions of Burgundy captured and razed the castle of Ornans, which was held by Burgundy of the King of France and was the strongest castle in the whole of Burgundy. And know that, I and my other comrades broke down the walls of the castle and forced our way inside, and secured the castle, and took nine prisoners and put a large number to the sword, apart from those who threw themselves down below the rock.”

In the second letter, written hastily after the first, Jean adds that French reinforcements have arrived in Burgundy. Thus, Jean cannot leave to join Edward in Flanders as quickly as he would have liked.

Edward's fortunes have improved slightly, but his position is still fragile. Two-thirds of Flanders has been overrun by the French, and his allies will not reach him before the middle of October at the earliest.

To add to his problems, some of his allies are now fighting each other. Jean de Chalon's brother, Hugh, Bishop of Liége, is at war with Duke John II of Brabant over the city of Maastricht. Both men are also part of Edward's coalition against the French. Duke John, a noted Anglophile, is with the king at Ghent:

“The Duke of Brabant was also there

with many men, as you should know,

from his land, and also with many

from the borders of the Meuse, many a lord,

and also from the Rhine.”

For the umpteenth time in his reign, Edward is asked to step in and resolve a dispute. He sends another of his capable agents, Aymon de Quart, to mediate between Hugh and Duke John. While messages go back and forth, a battle rages in the streets of Maastricht between supporters of the rival parties. A local chronicle describes the conflict:

“A dispute arose in Maastricht between the bishop's and the duke's men, because the duke's party were greatly oppressing our people. By no means able to bear this harassment for long, they rose against the Brabanters, and, behold, a great battle took place between them. But since the bishop's party grew ever smaller and the duke's increasingly larger, our men were unable to fight for long and were brought to the point of total surrender. Wherefore, the Brabanters split them up, killing or wounding some and taking others prisoner. The rest fled wherever they could.”

From this it appears Duke John's men win the battle. It occurs in early October: on the 10th Hugh writes a letter to King Edward, complaining of the hostile acts of the Brabanters.

The king perseveres with his diplomacy. At the same time one royal eye is anxiously watching the German border for any sign of another ally, Adolf of Nassau. The other looks south-west, towards the French army encamped at Ingelmunster. Will Philip the Fair advance to offer battle, or stay put? No doubt to Edward's relief, the French don't budge.

Thanks to the frantic efforts of Aymon de Quart, the war in Liéges is quickly resolved by arbitration. His competence is hailed on both sides. He is yet another of the many Savoyards who entered Edward's service as soldiers, diplomats and engineers. Appointed canon and provost of Beverley Cathedral in Yorkshire in 1295, he will go on to become Bishop of Geneva.

Published on October 09, 2021 04:16

No comments have been added yet.