Three days at Camp David and a year in Cyprus

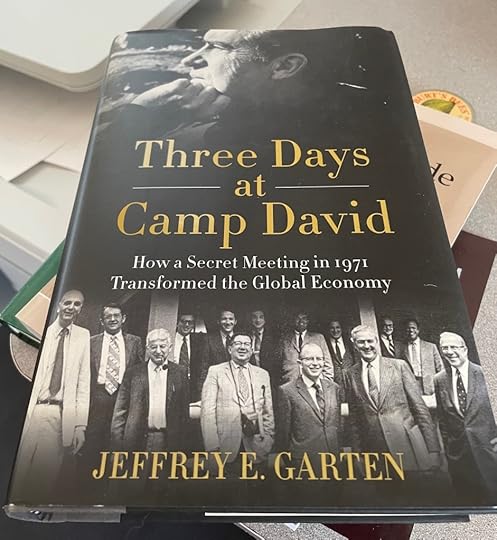

Jeffrey Garten’s new book, Three Days at Camp David,has worked its way to the top of my reading pile. Why would I want to spend some 300 pages studying a change in monetary policy from 50 years ago?

Well, I’m a bit of a money nerd, having covered business for more than 30 years, including a decade or so covering regional Federal Reserve banks. But the main reason is more personal. The Camp David meetings in 1971 led to President Nixon’s decision to sever the dollar from the gold supply. The effects of that decision hit home for my family a year later and half a world away.

In 1972, we had moved to the Mediterranean island nation of Cyprus, where my father was reassembling the sunken fragments of a 2,300-year-old Greek merchant ship in the coastal hamlet of Kyrenia.

My book, The Man Who Thought Like a Ship,tells the story of how my dad, a small-town electrician at the time, found himself in a position of rebuilding an ancient ship on the other side of the world, but the point is that then, as now, nautical archaeology doesn’t happen without funding.

My parents were counting on a UNESCO grant to pay our living expenses for a year. The grant not only paid my father’s salary, it also had an expense account that enabled him to buy tools and equipment.

The decision to decouple the dollar from the gold standard caused the dollar’s value to fall, and the decline accelerated as the Watergate scandal unfolded. UNESCO paid its grantees in U.S. dollars, but the Cypriot pound was tied to the British pound in those days. At first, my parents just faced the concern that the money wouldn’t go as far. Then, UNESCO began cutting back on grantees, starting with the newest ones. My dad was near the top of the list.

He was chasing a dream, but he was also practical. He told Michael Katzev, the director of the Kyrenia Ship Project, that without the grant, he’d have to return to the U.S. and resume his electrician’s job. He support a family on no income.

It was the first time I remembered my parents being openly worried about money. They rarely discussed their finances, and in fact, I had no idea what my parents made or how grave the situation in Cyprus was until I started writing my book. But I remember my mother telling me we might be leaving early, and I knew my dad would never leave the Kyrenia Ship unfinished unless the situation was dire.

When you’re a child, seeing your parents in distress leaves an impression. So I wanted to understand more about this monetary policy decision that wound up having such an impact on my family.

Our personal crisis itself was averted. Katzev told my father he would figure something out, and he did. “Michael somehow scraped some funding together to keep me on; I have always suspected it was his own money,” my dad wrote years later.

The financial struggles would continue for the next few years, and my dad did, in fact, go without an income for a few years until he joined the faculty of Texas A&M University in 1976.

The Camp David meetings may have “transformed the global economy,” as Garten’s subtitle says, but it almost undermined the transformation of my father’s career and derailed his dreams.

In a subtle way, it also influenced my approach to business writing. I’ve always gravitated toward stories about the unintended consequences of money, and as a columnist at the Houston Chronicle, I frequently wrote about how esoteric monetary issues affected ordinary people, often in ways they hadn’t thought about. So I’d like to better understand one of the most important money policy decisions of my lifetime, and I’ll be interested to read Garten’s perspective.