CMP#69 The Bristol Heiress, part two

In today's post we're looking at a five volume novel, The Bristol Heiress, by Eleanor Sleath.

In today's post we're looking at a five volume novel, The Bristol Heiress, by Eleanor Sleath. For more posts about now-obscure 18th century authors, click the category "Authoresses" to the right CMP#69 I'll See Your Three Volumes and I'll Raise You Two More

Nobleman seeks rich merchant's daughter for matrimony In

my last post

, I shared some similarities between an 1809 novel, The Bristol Heiress, and Northanger Abbey. Most of the Austenesque coincidences came in the first and second volume of The Bristol Heiress. There's a lot more novel to get through. Spoilers ahead!

Nobleman seeks rich merchant's daughter for matrimony In

my last post

, I shared some similarities between an 1809 novel, The Bristol Heiress, and Northanger Abbey. Most of the Austenesque coincidences came in the first and second volume of The Bristol Heiress. There's a lot more novel to get through. Spoilers ahead!This novel features the popular themes of: (1) faulty education for girls and (2) London as a sinkhole of vice

Caroline Percival, our heroine, is the daughter of a rich but low-born (ie merchant family) mother and a well-born banker. The wife's money is necessary to the plot, but she isn't, so she's dispatched at the beginning of the novel. The father sends his only child, Caroline, to a boarding school in London to learn from the best masters. She grows up to be a beauty and she's taught all of the basic ladylike accomplishments. Her aristocratic aunt Lady Harcourt takes her up. Dad is thrilled because with Lady Harcourt to escort her around London society, Caroline has a good chance of making a brilliant match.

Decadent Lady Harcourt fastens on dad like a parasite, telling him he has to build a mansion and buy expensive clothes and jewels for his daughter, but a lot of the money goes into her pocket. Although Mr. Percival's fondest dream is to see his daughter with a coronet on her head, he lets the handsome but poor young clergyman Mr. Griffiths escort his lovely young daughter around the countryside every day to give her painting and sketching lessons. Of course the young people fall in love, but he can't speak because of the wealth gap between them and she won't admit her love because her ambition is to marry a rich aristocrat.

"Methodist Parson, Stark Mad!" After going to London with Lady Harcourt, Caroline makes a sensational debut with the ton and attracts the attention of a number of suitors, but dad and Lady Harcourt hold out for the best offer--from the son of an Earl who is in the market for an heiress-bride. Caroline also meets an assortment of selfish and unlikeable people. Her aunt hosts nightly card games at which everybody loses money. In other words, London society is presented as a venal and unpleasant world where everyone is obsessed with appearances. Yet, this is where everybody wants to be, including Caroline.

"Methodist Parson, Stark Mad!" After going to London with Lady Harcourt, Caroline makes a sensational debut with the ton and attracts the attention of a number of suitors, but dad and Lady Harcourt hold out for the best offer--from the son of an Earl who is in the market for an heiress-bride. Caroline also meets an assortment of selfish and unlikeable people. Her aunt hosts nightly card games at which everybody loses money. In other words, London society is presented as a venal and unpleasant world where everyone is obsessed with appearances. Yet, this is where everybody wants to be, including Caroline.Then things go badly for our heroine; dad loses all his money in a bank failure and dies. The engagement is called off, and Lady Harcourt even kicks Caroline out of the house. As with other novels of this type, (such as Ethelinde) this means she has to go and live with other various disagreeable relatives, including an aunt who is being preyed upon by a Methodist preacher who is really just a grifter. (I've recently read several novels with unflattering portraits of Methodists and puritans, so this will be another future blog post).

Caroline is not a "picture of perfection" heroine. At several points in the novel, she has the chance to turn her back on worldly ambition and marry the young clergyman Mr. Griffiths, and every time, she rejects him in favour of the pursuit of wealth. The dramatic tension in the story arises out of her fruitless quest for happiness through vain and worldly pleasures.

There is also a subplot about a " picture of perfection " heroine named Matilda, her brother Darnley, and her long-lost husband. This subplot starts when Caroline is riding around London with her friend Lady Mary. In a heavy-handed scene, Lady Mary is distraught when her dog's leg is injured but indifferent when her carriage rolls over a little child in the street and breaks his leg. Caroline goes back a few days later to enquire if the child is all right and meets Matilda, a beautiful and well-born lady who is down to her last shilling. While she calls herself 'Mrs.," the landlady is skeptical and hence rude to her. Caroline also isn't sure if she should give charity to a fallen woman, let alone be in the same room with her, but she helps out for the sake of the lovely little boy. In time we learn Matilda's mysterious backstory and through a string of amazing coincidences, which are handled very briskly in comparison to the main plot, Matilda is happily reunited with her husband and her brother. This is one of those plots which would never work today in our modern age with cell phones and email. Romeo to Juliet: U dead? Juliet: Lolz No!

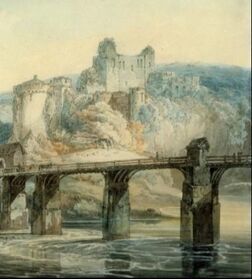

Chepstow Castle, detail, Turner, 1793 Meanwhile, Caroline manages to captivate Lord Castleton, a very wealthy but older nobleman. But we're just at volume 4 and there's another volume to go. More tribulations and misunderstandings follow.

Chepstow Castle, detail, Turner, 1793 Meanwhile, Caroline manages to captivate Lord Castleton, a very wealthy but older nobleman. But we're just at volume 4 and there's another volume to go. More tribulations and misunderstandings follow.Volume 5 is padded out with a segment set in an old castle in Wales, where Caroline has been banished when her husband suspects her of infidelity. Caroline hasn't been unfaithful, but she has been vortexing -- that is, getting caught up in the London social whirl, losing money at the card table, flirting too much. A jealous rival, Miss Moreland, manages to plant suspicions in her husband's mind. While there, Caroline comes across an old manuscript which I've excerpted below; a gothic tale which is a complete break from the main narrative.

With the help of the clergyman of the parish (what a coincidence, it's Mr. Griffith!), the misunderstandings are cleared up. Then everybody goes travelling. We have a travelogue about Wales and a digression on the poet Ossian . Finally we see Caroline--and basically everybody else--happy. Plus Miss Moreland gets religion and dies, and the evil Lady Harcourt gets her comeuppance but Caroline graciously forgives her.

I do think Eleanor Sleath was playing with our expectations a bit when Caroline didn't end up with the handsome clergyman from Volume I. Is Sleath subverting the typical marriage plot? We don't even meet Lord Castleton until Volume 4 and he's not a young romantic hero. He is a bit of a hypochondriac and very strait-laced. He does learn however, that he is happiest when he is fulfilling his responsibilities to his tenants and to his fellow man. Caroline wasn't really cut out for life as a clergyman's wife, so all's well that ends well.

The Awakening Conscience (detail) by Hunt, 1853 Sleath concludes: “Let those, then, who have endeavoured, like [our heroine], to win the phantom, worldly enjoyment, through the mazes of dissipation and luxurious indulgence, learn from her history to see that wealth and splendour can only be valuable when usefully applied—that a life devoted to fashionable pleasure is a life of labour, vexation, and pain—and that true satisfaction and sound enjoyment can only be expected and found in such pursuits as are founded upon good sense and wisdom, resting upon such principles as religion may dictate, and sound morality approve.”

The Awakening Conscience (detail) by Hunt, 1853 Sleath concludes: “Let those, then, who have endeavoured, like [our heroine], to win the phantom, worldly enjoyment, through the mazes of dissipation and luxurious indulgence, learn from her history to see that wealth and splendour can only be valuable when usefully applied—that a life devoted to fashionable pleasure is a life of labour, vexation, and pain—and that true satisfaction and sound enjoyment can only be expected and found in such pursuits as are founded upon good sense and wisdom, resting upon such principles as religion may dictate, and sound morality approve.”To return to the consideration of money and class in books of this sort, it seems to me that this is a kind of "have your cake and eat it too" story. We read many details about lavish wealth and the high life in London, and both of our heroines end up rich, but at the same time the author assures us that money does not bring happiness.

I do not see the treatment of money and class in The Bristol Heiress as representing a critical examination of social class in England, I see it as a book written to meet the prevailing tastes of a middle-class audience who are fascinated with a lifestyle they want to vicariously live while at the same time condemn. The poems supposedly by Ossian, a mythic Gaelic bard, are now generally thought to have been written by James MacPherson (1736–1796). The debate over whether Ossian's poems were genuine or fabricated was a hot topic at the time.

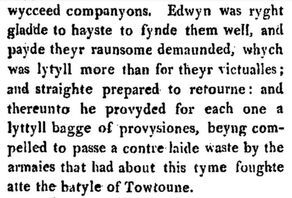

Eleanor Sleath also tried her hand at some old timey language in the fifth volume of The Bristol Heiress, when she threw in a short story for the heroine to read about a medieval lady in distress during the Wars of the Roses. More about Eleanor Sleath (1770-1847) at the "SleathSleuth" website.

excerpt from The Bristol Heiress, Vol. 5, p. 164 In Mansfield Park, Mary Crawford is attracted to Edmund Bertram, but she doesn't want to be a clergyman's wife in a small English village; she wants to live in London, which would more than what their "incomes united could authorise." If Mary wants a better lifestyle, she needs to find a richer husband. In my Mansfield Trilogy, I explore the possibility, what if Mary and Edmund did get married?

Click here for

more about my books. Click here for the introductory post in the "Clutching My Pearls" blog series.

excerpt from The Bristol Heiress, Vol. 5, p. 164 In Mansfield Park, Mary Crawford is attracted to Edmund Bertram, but she doesn't want to be a clergyman's wife in a small English village; she wants to live in London, which would more than what their "incomes united could authorise." If Mary wants a better lifestyle, she needs to find a richer husband. In my Mansfield Trilogy, I explore the possibility, what if Mary and Edmund did get married?

Click here for

more about my books. Click here for the introductory post in the "Clutching My Pearls" blog series.

Published on September 09, 2021 00:00

No comments have been added yet.