Pendragon Saga: Chapter 2

Prince Arthur II of Deheubarth

House Words: Son of the Dragon

Standard: Crown of Or on an Azure Field

Living Members: 6

September 28, 892

Prince Arthur felt the cool sea spray against his eyelids, listened to the distant wash of the Môr Hafren. Nearby, on the muddy bank of the Wysk, he could hear the laughter and curses of peasant labourors gathering timber and stone, storing it in an old, repaired Roman storehouse. More supplies would arrive throughout the winter, and at the first thaw construction would start on a modest harbor for Caerllion.

“Admiring your new port, my prince?”

Arthur slowly opened his eyes and glanced over his shoulder. An old, one-eyed man on a palfrey sidled up beside him. Arthur reached out and clasped the hand of Hywel, his long serving steward, and his long serving lover.

“Only 25 autumns later.”

“You did say it would be years in the doing.”

And indeed the young lord had been right all those years ago. Now, at 41 winters, Prince Arthur of Deheubarth felt like he had lived several lifetimes in two decades.

*

His early years had been marred by failure and humiliation, some his own fault, some the simple whims of fate.

The first war he had lost was on the domestic front lines. Arthur had assumed when his Irish wife arrived there would be some time before she felt at home. What he hadn’t prepared for was how cold and difficult his wife would be. Lady Gormlaith had a quick temper, yet rarely said what she actually felt. He had attempted to provide some intimacy in their marriage bed, but she had rebuffed him. “I simply don’t feel the same way as you do, my lord,” she had offered the first night he had dismissed all the servants and invited her to his chambers.

She believed she had already fulfilled her marital duties by providing him with an heir not long after their marriage. She did not seem interested in more children in any hurry.

He had seen victory in battle, of course. But while he wore scars, deep gashes across his face, while peasants and nobles alike marvelled at the scarred warrior lord, few knew the scares were the result of an embarrassing training accident. Not long before that first failed siege of Caerdydd, he and Ithel had taken their knights field riding, and set up a course to simulate ambushing infantry in a forest. Leading one flank, young, invincible lord Arthur had decided to push through a tricky bit of bramble for a more aggressive charge. He had roared in fury like an Irish barbarian as he led the offensive. After inevitably getting thrown, he came to with the world spinning, his head throbbing, his vision the red of blood in his eyes. Nothing lasting, save the scars, but it had tempered his daring somewhat. Lucky he hadn’t driven his own sword through his eye socket, an ignoble end to the short lived reign of the last Pendragon of Gwent that would have been.

The true training came on the battlefield, a lesson in humility, how arbitrary the fortunes of war can be. Just as he had ordered, old Bishop Rhiwal had produced a claim on the lordship of Morgannwg. They had gathered their soldiers at Trefynwy and marched on Caerdydd. They laid siege to the cowardly Prince Hywel for months, were close to taking the castle, when two riders came. The first a messenger from Caerllion who had rode hard, vikings were raiding Gwent. The second a scout from the barrowlands up near Brecon. A sizeable force of soldiers flying the standard of Gwynedd had joined with the levies of aged Lord Elisedd of Brychcheiniog and marched on Caerdydd. There was confusion, were they coming to the aid of Prince Hywel? No, Elisedd was rebelling over some taxation the coward had imposed, and had Lord Elisedd’s wife’s family, the soldiers of Prince Rhodri the Great, joined the small rebellion.

Arthur broke the siege and ordered a march on Caerllion. If they hurried, they would miss being caught in the infighting between Rhodri and Hywel, and could come back later and take the keep once the Gwynedd forces had won. Too late, Prince Rhodri’s soldiers caught the forces of Gwent near the bishopric of Caerffili, charging them on sight as Arthur’s small force retreated. Too late, Arthur sent a messenger to Rhodri and Hywel, a white peace surrender, but his levies and men-at-arms had been whittled down, too many dead not from the war he had started, but a war they should have had no part in. Too late, the survivors threw themselves at the northmen barbarians raping and pillaging their way through the village, and Arthur was delivered another humiliation as he ordered a retreat, overwhelmed by their numbers and ferocity. When his routed forces had rallied and returned to the keep, they found homes burned, a keep ransacked, hostages taken, and more dead than Caerllion had seen in decades.

Lady Gormlaith had been taken, as had the wife of one of his knights. Aunty Agnes had been killed in the slaughter, as had his spymaster Eurowyn. Those weighed heavy on him, especially Agnes. As they recovered and rebuilt, he had to sit across the table from Cynwallon, whose eyes were always red and whose interest in the rule of Caerllion dwindled, even as he remarried a beautiful Cispaline woman. Eventually Arthur allowed him to return to the village and live the rest of his quiet life, replacing him with a gentle giant from Ireland named Murchad.

Arthur was numb all during that time. The war he’d abandoned had drained the coffers of Caerllion, with no loot from taking the coward’s keep to build on, and so he was forced to sit and watch as the silver trickled in. Life had taken on a kind of surreal normality. He was little more than a farmer with a fancy little fortress, so he had spent time patrolling his land with his men, settling minor disputes, helping the small farmsteads rebuild and sow a new harvest, raise his son.

He missed even the occasional times Gormlaith would share his marital bed. However neglectful she could be, he was comforted by the sound of someone sleeping next to him. Even with all the distractions of rebuilding he had been lonely. Perhaps that’s why he’d turned to Hywel.

While they rebuilt the village, Arthur began to meet with Hywel at least once a week to discuss the harbor. An idle fantasy given Arthur couldn’t even afford to ransom his wife back from barbarians, but it gave him something simple to look forward to; building something new.

It happened the first time they rode down to survey the old Roman ruins, all those years ago.

A beautiful summer day, the kind that is coloured golden in memory. Motes of pollen drifted lazily through the gentle, intoxicating breeze. The two men dismounted, letting their horses nibble on grass, and Arthur began to take notes with the occasional, sardonic comment from Hywel.

Eventually they sat on the bank of the Wysk and shared a flagon of water, and some bread and cheese.

“I’m very sorry about your wife, m’lord.”

Arthur looked up at his steward. The older man seemed genuine, a change from his usual teasing.

Arthur shrugged, “Truth be told, it only means I sleep alone a little more often than if she were here.”

He had no idea why he would admit such a thing to someone lowborn, a peasant, an apple picker. He didn’t know why, but it felt like Hywel had offered something, and Arthur had returned the sentiment. As if a key had opened a lock.

He’d expected to be roundly teased by his steward, but Hywel merely lifted himself up from the ground to sit on the stone next to Arthur. “You shouldn’t have to sleep alone.”

Arthur felt a heat ignite deep in his gut, “You seem to have no problem doing so.”

Hywel grinned, and young Arthur melted. “Who says I sleep alone every night?”

“If you’ve ever snuck a strumpet into your cottage, you’ve hid it from the village gossip-mongers quite well.”

“And who says it would be a strumpet I sneak into my cottage.”

Arthur’s stomach dropped out, and he gulped nervously, like a dumb show character as he felt a hand cup his basket.

“Apple pickers tend not to care which tree they pick from, or at least not the ones I know,” Hywel murmured tenderly as he stroked his liege. “There’s a great deal you could learn, m’lord. A great deal I could teach you.”

Arthur reached down and clasped Hywel’s hand. The peasant man’s eyes went wide in fear, but Arthur merely raised the hand to his mouth and kissed it tenderly. “Thank you for your counsel, steward. I will take your proposal under advisement.”

Hywel smiled that same rugged, crooked-tooth smile. He could feel Arthur’s hand trebling. He had felt how his liege… reacted to the advance.

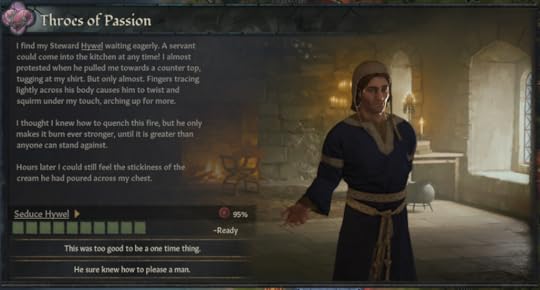

Arthur became consumed by the exchange, he began to seek out any time he could to meet with Hywel to discuss the port. They would ride down to the river on pleasant days, pretending to plan the harbour, or drink wine and talk late into the night in the kitchen, picking at the last remnants of the evening meal. Hywel allowed Arthur to make his own approach. Hywel received a small silver locket and had worn it every day since given, which Arthur took as a good sign. One night, in a fury of passion, Arthur sent for his steward to meet him in the kitchen to discuss something of great importance.

Arthur wanted to confess how his adoration for Hywel had blossomed, but they came together violently, like a storm over the channel. Arthur almost told Hywel to stop as he found himself pressed against a countertop. It was late, but that didn’t mean a servant wouldn’t come to finish their duties, or a coal boy wasn’t skulking nearby. But as Hywel ran his hands under Arthur’s shirt, the young lord returned the gesture and found a power in his hands on Hywel’s body as his steward squirmed in pleasure.

They did not entirely consummate their love that evening, that came a few days later, but Arthur returned to his chambers with Hywel’s issue coating his chest. Arthur had hoped confessing would help temper these feelings somewhat, but he hadn’t confessed and their joining hadn’t tempered anything. He burned for Hywel.

Meanwhile, Caerllion would receive occasional messages from Gormlaith and the Irish noblewoman, the wife of his knight Sir Einion. The council was disgusted when, about a year after the raid, word came that the Jarl of Mann had taken the noblewoman as his concubine. Arthur feared for the day the same message would arrive about Gormlaith, thrown to be rutted by those feral sea snakes. Her only protection was her worth for ransom. Arthur didn’t even succeed at that, Lady Gormlaith arrived at Caerllion in rags a few years after being taken. A Cumbrian petty king of the north had taken Mann and released the jarl’s prisoners. She had been freed by the whims of fate. Failure after failure.

While he had taken Caerdydd not long after that, tragedy continued to dog him for a time. He brought on Ithel’s wife to replace Euronwy. Ealdgyth was a shrewd, bold, callous woman. Well suited to the work, but not well suited to win any hearts. She and Gormlaith loathed one another, his wife’s temper setting off Ealdgyth’s paranoia–council meetings were tense when both women were present, everyone waiting for one to set off the other–so when a coal boy discovered Gormlaith stabbed to death in her chambers, her jewelry stolen, Arthur had his suspicions. Of course Ealdgyth was nowhere near the keep the evening of Gormlaith’s death. She had enthusiastically investigated the murder but found no evidence and believed it was a theft gone awry. Arthur had sat with the evil shrew at the council table, wondering, for 18 years.

Still, however awful Gormlaith’s death it was something of a relief for Arthur. He sought out a landless Dutch noblewoman renowned for her beauty, shy but headstrong and level-headed. No significant allies, but loving Lady Cecily as a wife was no more a challenge than bedding her, and she gave him many beautiful sons. The way he dreamed marriage to a good woman should be.

*

“Lost in thought, m’lord?”

Arthur blinked away the fog of memory. “Just thinking of that rock by the river.”

Hywel smiled and dismounted–with some difficulty. At 54 summers the man was ancient compared to most of the villagers, healthy for now, but his youthful vigor faded with every year. He was slower now. Arthur climbed off his palfrey and the two men’s lips met. Hywel reached for Arthur’s cock, and even at the advanced age of 41, he responded like a man half his age. They rutted slowly, carefully, they both had aches and pains and old wounds. After they lay together half-dressed on a bower of grass watching the sun set over the channel.

They perhaps didn’t take as much care as they should. Ealdgyth had come to Arthur one night with news that a roughly dressed man had been seen sneaking out of Hywel’s cottage late at night by an inquisitive neighbour–probably some opportunistic crone who received a little gold for spying on the steward. Arthur assumed the man was him… or else one of Hywel’s apple pickers. He’d never told Hywel, only kept their assignations more contained. Hywel was one of his knights, after all, and a knight always stood guard by their lord’s chambers at night. A convenient occasional excuse to spend the night together.

Arthur turned and studied the sun-browned, weather-lined, battle-scarred face of his paramour. Hywel had lost his left eye in the fight for the Principality of Deheubarth. A holy battle, given the how it was instigated, so Hywel joked that he was now “hole-y-er” too.

In the aftermath of the devastating Viking raids from Mann, Arthur had travelled to Canterbury, partly for some new perspective, partly to get away from the death that walked the halls of Caerllion in his mind. At the encouragement from the bishop of Canterbury, Arthur had written to Pope Marinus to describe Gwent’s tribulations, and to Arthur’s surprise the great man responded with a small fortune of gold and kind words, and they’d kept up an occasional correspondence. All the more surprising, when Lord Arthur politely invited Pope Marinus to a St. David’s Day feast and celebration in 880, the Pope accepted. The court had never seen such festivities, nor so many Italians. Marinus was an honest, patient man, but had a bawdy side Arthur found as surprising as their friendship. After years of lessons from Hywel, Arthur even noticed subtle signs that maybe the supreme pontiff was not entirely unlike him. The man complimented boy servants just as quickly as the young women of the court. Arthur caught him admiring the prat of Sir Cadfan, one of his knights, as the other man bent over the side of a post in the training yard. The last thing he expected was to catch the Pope’s eye, and have the bishop of Rome wink at him playfully. At the St. David’s Day feast, the Pope was seated at the place of honour in Caerllion’s hall. As the dancing began, he and Arthur were discussing cowardly Prince Hywel of Deheubarth’s retreat into the hills of Aberhonddu, displacing Lord Elisedd and his family. Marinus said, given the right sway among the clergy, he could make inquiries and transfer the Principality to Arthur, and the lord could claim Deheubarth.

“The Holy See is always prepared to assist the righteous,” Marinus said with a knowing smile, reaching over and patting Arthur’s thigh. The touch lingered, the man’s fingers inched upward slightly. He was a man of 61 years, but healthy, and of healthy appetites, clearly. Arthur was genuinely flattered, and not the least bit intrigued. Did the fucking Pope really want to lay with him?

The hand was retracted, although not the offer of aid. A few years later the man did indeed grant Arthur a claim on the Principality of Deheubarth.

The cowardly prince was injured in the fighting and promptly died, leaving the castle of Aberhondu to his grandson. After taking Caerfyrddin from his rival Prince of Gwynedd, the Lord Hyfaidd of Dyfed to the west presented himself as a vassal of Prince Arthur of Deheubarth. The young warrior now controlled a small principality; hard fought and hard won, but it was his.

Princess Cecily, Prince Arthur and the late Uther ab Arthur on Arthur’s ascent to the Principality of Deheubarth.

Princess Cecily, Prince Arthur and the late Uther ab Arthur on Arthur’s ascent to the Principality of Deheubarth.Not without sacrifice. War was terrible, to see men stagger, bloody, practically cloven in half, tripping and slipping over the viscera of their fallen comrades and enemies, blood pooling dark and baleful in the mud. Arthur counted every loss as a personal failure, and was most anxious about his brave knights, anxious to see them stumble or ride across the charnel landscapes of victory. Loyal Sir Gerallt, an unlanded young knight and exceptional warrior, lost a leg and was disfigured so badly he no longer showed his face; big, kindly Murchad had been maimed so badly in the fighting he succumbed to his wounds despite the best treatment; Hywel lost his eye.

Arthur turned to Hywel, who dozed even as the cool sea air became cooler in the evening. “Does your eye still bother you much?”

Hywel stirred, smiling sleepily, “Only when handsome princes ask about it.”

Arthur smiled. He loved Hywel, more than he had ever been able to say. He’d tried to confess his feelings on a couple of occasion, wanted to dedicate himself to his steward, and have Hywel do the same. He’d been rebuffed not once, but twice. Hywel was happy with the… physical nature of their assignations, but did not seek more for his own reasons. Arthur had accepted this now, but wondered what he would do when elderly Hywel passed.

Despite all the loss, all the destruction, all the death, crops were sown, harvests were reaped, weddings were celebrated, babies were born, boys were trained at swords and now Hywel and Arthur had their port.

They dressed and mounted, Arthur riding a little gingerly after their rutting, he wasn’t a young man any more. Arthur’s heart sank as they left their sunrise behind and rode towards the distant glow of Caerllion, still clad in black pennants of mourning at his son and heir’s death. Hywel glanced nervously at his liege before bidding him good evening. A quick clasp of their hands and Arthur spurred his mount on up the hill, dreading finding his home as quiet as a tomb.

His third son and squire, Mordred, almost a man himself, was waiting in the stable yard along with his other squire, Lord Hywel, a boy of twelve winters. Arthur had taken young Hywel under his wing after the boy was unceremoniously pronounced Lord of Brycheiniog and vassal to the new Prince of Deheubarth… the man who had cut away at his family until there was little left. Arthur hoped they would develop a friendship over a shared love of martial training, and the boy was already showing a Christian bravery that bordered on zealotry, a religious worship of the Crusades. Mordred, tall and bright with Arthur’s good looks and his mother’s dark hair and dark eyes, had taken more to the tenets of chivalry than his fellow squire. He was brash and impatient, sure, but his bravery and sense of honour reminded Arthur of himself at that age, ready to forge a kingdom.

“Father,” Mordred gave a curt bow.

“My liege,” Lord Hywel followed the gesture.

Arthur smiled to himself as he climbed off his mount. He clasped his squires on their shoulders affectionately. “You two didn’t need to wait up, the stable boy could have seen to this old nag.”

The two boys went about leading the palfrey into the stables and began removing the old, cracked saddle, Hywel with a horse brush in hand. He’d trained them well, a lord who was not afraid to do the work of a stable boy was not too proud to care for his people.

Mordred looked grim, “Mother was worrying after you. Arthwr is with her in her chambers.”

Arthur patted his son’s shoulder affectionately and promised they would go field riding the next day.

Up the steps of the keep, through the hall and into the family’s quarters, Arthur found his wife dressed in mourning black, smiling serenely at her beloved son, Arthur’s now heir. The moon glimmered and shivered in the reflection of the distant river. Even at 43, Lady Cecily was a beautiful woman, intelligent eyes and a calm, soothing soul. But a quiet reserve of strength. Little Arthwr, first born to Arthur and Cecily, had inherited her beauty, though had his father’s gold-spun hair and sea-blue eyes. Since the death of Uther, he’d taken his brother’s seat as chancellor at the council table. While less of a student of statecraft than his late half-brother, he still exceeded him in intelligence and cunning. Arthur was intensely proud of his sons.

The late Uther, Arthwr, Mordred, Hywel and the twins Morgan and Owain.

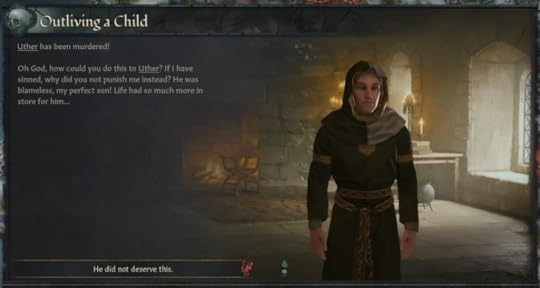

The late Uther, Arthwr, Mordred, Hywel and the twins Morgan and Owain.“Husband,” Cecily stood and ran into Arthur’s arms, sniffling. While he wasn’t her trueborn child, she had taken Uther’s death hard. He’d been murdered in cold blood, found stabbed to death in his chambers, like his mother. The first time since Lady Gormlaith’s death such violent tragedy had infiltrated their humble court. Athur knew Cecily doted on her children, and worried herself sick the same fate could be theirs. His spymaster was currently investigating the murder quietly, but until they had any answer an air of fear and suspicion chilled the court. Arthur, as always, feared Ealdgyth might be involved. If it was an assassination, if it was planned, either she was a poor spymaster or she was complicit.

“Any news, my lord?”

“None,” Arthur admitted. He would meet with Ealdgyth soon to see if she had discovered anything suspicious, but until then they were all fumbling in the dark. He walked over and clapped his hand on Arthwr’s shoulder, who patted it affectionately.

“How’s Hywel?” Arthur asked, “the twins?”

Arthwr rolled his eyes, “Hywell’s skulking about like usual, scaring the servants, playing spymaster.”

“The twins and I had the most wonderful game of pick-up-sticks today,” Cecily smiled warmly. “They were hoping you’d take them riding tomorrow.”

“I will, wife,” he kissed her, a simple peck. She looked at him with a mournful longing.

“Shall I join you in your chambers tonight,” she whispered, although Arthur had to believe their poor son could hear.

“I had a long day, I don’t think I’m long from sleep,” she nodded, smiling through her disappointment. “Why don’t you go and see the twins get to bed, I’ll come and say goodnight to them presently.”

“Yes, my lord.”

Cecily strode from the room, her black gown fluttering around the corner of the door. Arthwr stood and went to the hearth, throwing another log in to keep the fire going.

“She worries about you, father.”

Arthur sagged down in the chair, and his son came over and crouched beside him, clasping his hand over his father’s.

“We all do.”

Arthur gave his son and heir a sad smile, “It will pass, this dark cloud. We’re all still in mourning.”

Although Arthur didn’t believe that, nor did his perceptive, empathic son. Since Uther’s death a darkness had gripped Athur’s soul. There were moments he didn’t feel like himself, like time dragged out too long and little details became cataclysmic, moments where he felt like ending this whole tragic existence. He carried on for his wife, his children, his lover, his people, but the world seemed greyer, flatter, like all the colour had gone out of it. Happiness came less frequently, and rarely lasted more than a moment.

He had spoken first on the matter with the court physician, Menechem, an aged and wise Ashkenazi Jew who had stumbled into court looking for a home more than a decade ago. The man proclaimed that Arthur’s humours were unbalanced, prescribed a bloodletting, but Arthur didn’t see how that would heal his soul. Next he’d gone to his new bishop, Mraczysław, an odd little Polish man, the second son of an ousted count from the incessantly warring kingdoms across the channel. He was a drunk and a madman, Arthur thought that the captivity that killed his father likely broke him. But he was more intelligent than Rhiwal and a good deal more of a hard worker, so Arthur did not begrudge him a little lunacy.

Slurring, Mraczysław had quoted Revelations: “He will wipe every tear from their eyes. There will be no more death or mourning or crying or pain, for the old order of things has passed away.” Arthur was not the most religious man, but found some comfort in that. The thought of the old order dying away, a good, eternal Christian peace replacing it…

Arthur took his hand and placed it over his son’s. “You’re a good man, Arthwr. You’ll make a good father.”

He kissed his son on the forehead and stood, grunting from his exertions with his lover earlier. Any priest would say he should feel guilt about going to his family, discussing his son’s death, while the issue of his fornicating, sodomitical lover dried between his legs. He’d felt guilty about it at first, but time had a way of working away at things until they were worn smooth, like an old runestone deep in the woods. Maybe the grief and melancholy that gripped him since his son’s death would soften over time… he hoped…

Uther ab Arthur of House Pendragon had been born to Gormlaith, her only child before her untimely death, when Arthur was only 18, still feeling like a child himself. He’d survived that Viking raid, hidden away by the women with some servants in Caerllion’s earth cellar. He’d survived his mother’s disappearance, and her violent death. He had been a hardworking, just boy, virtues marred only by his utter cowardice. Uther had struggled to even pick up a sword, let alone have any desire to wield it, mystifying to his warrior father. Still, a charming, well liked boy who became an intelligent, diligent young man. He left behind a wife, a beautiful, drunken Bavarian no one in Caerllion could understand and who most people avoided. No children, the biggest heartbreak of all. He was dead and would likely pass out of memory long before the rest of his brothers. Eventually there would be no one left to mourn him.

Arthur checked in on Cecily and the twins, gold-haired Morgan and dark-haired Owain. Morgan was splayed out on his bed, head resting in his mother’s lap, chattering away about his studies that day, a bookworm from the moment he learned to read. Arthur wondered if maybe he would do better in the priesthood than a life of heartbreak, pain and dead children.

Fidgety Owain was up on his feet, wooden sword in hand, going through his form, but dropped it and ran over to his father, throwing himself into Arthur’s arms.

“Father! Father! Mother said you’d take us riding with Mordred and Hy tomorrow!”

Arthur ruffled Morgan’s curly mop of dark hair, with a smile and a nod. Owain whooped and ran around the room, collecting all the things he would need tomorrow. Arthur bid the twins a good night and headed to his chambers.

Mercifully, the coal boy had built up a fire, likely sent along by Arthwr or Mordred. Arthur dropped himself into the large, plush chair before the fire, feeling exhausted down to his bones. He would get himself to bed soon, alone. Soon he would receive word from his deceitful spymaster. Tomorrow he would meet with his council to discuss their next move in liberating Wales from the Aberffraw line.

Like his lover, like his family, like the port, maybe reclaiming Wales would distract him from this deep, aching pain.

Maybe.