Part One: Piranesi

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, 1720-1788

As a scientist and an explorer I have a duty to bear witness to the Splendours of the World…— Piranesi, Susanna Clarke

Hello, friends. I’ve been counting down the days to the commencement of our summer book club on Piranesi by Susannah Clarke… and it’s finally here! I’ve hosted an online bookclub each summer for the last four years, and every year I enjoy it more than the last. I’m excited to invite you into the world of this strange and beautiful book. You can read more about why I chose Piranesi in last week’s post, and catch all the details for how the book club will run at the bottom of this page. In this first episode I talk with my brother Joel Clarkson about our experience reading it out loud together last autumn, and give a literary and thematic introduction to the book. In this post, I want to offer some of thoughts, and draw your attention to two important themes in the book:

Alienation and Kindness.In his essay “The Rediscovery of Meaning,” Owen Barfield tries to account for the “pure cussedness” of the fact that “the more able man becomes to manipulate the world to his advantage, the less he can perceive any meaning in it.” Barfield argues that when the scientific method hardened into an epistemological outlook, the horizons of scientific knowledge exponentially expanded, while the vistas of meaning began to contract. Ingrained to a “habit of inattention,” we began to treat the world as an object quite separate from ourselves, and thus quite alien. We are alienated from the natural world. We speak of the “environment” as if it is something quite separate from ourselves, and not that from which these bodies of ours draw their very substance.

What would it be like if we weren’t alienated from the natural world?This is one of the questions that Clarke imaginatively explores in Piranesi. She writes:

Ancient peoples did not feel alienated from their surroundings the way in which we sometimes do. They did not see the world as meaningless; they saw it as a great and sacred drama in which they took part. Barfield called this idea “original participation” and I tried to describe this sort of relationship in Piranesi’s attitude to the House.— Susanna Clarke, an interview in the Hindustan Times

This endeavour is tied up with another notion: disenchantment. The sociological historian Max Weber (1864-1920) famously argued that modernity was characterised by a movement toward rationality, which he describes as a process of “disenchantment.” Weber suggests that the pre-modern individual existed in an “enchanted garden,” a place full of mystery and meaning where the natural world was a book which revealed aspects of the nature of God, and everything oozed with a significance beyond its mere material existence. This notion has been picked up by authors like Charles Taylor who argues that the secular self perceives the world through an “imminent frame,” where God may exist, but nothing in the material world shares divine meaning or life. Taylor observes the perceived loss in the way that the modern person experiences the world. We live, as Alison Milbank writes in “the Kantian world of dead objects.”

So there is a sense of loss, of hauntedness. But what is the solution?

If you read very long you’ll bump into another notion: re-enchantment. If Piranesi embodies the “premodern man” who exists in a state of “original participation,” I think the Other, to whom we have been indirectly introduced in this first chapter, embodies a lonely modernist. He is convinced that there is some “Great and Secret Knowledge” hidden somewhere in the world. Something the modern world has forgotten. Something he must find and master. In this, however, he seems to demonstrate the very mindset Barfield argues destroyed “original participation” to begin with: the ability to “manipulate the world to his advantage.” This presents an interesting conundrum: nature is as ever it was, but we have lost touch with her, and the world seems drained of its vitality and beauty as a result. This loss of meaning is mirrored in the actual destruction of nature. We are less and less able to name nature, to feel its significance, and so perhaps unsurprisingly, the natural world is under threat. It is no tragedy to kill a “Kantian world of dead objects,” if it is, after all, already dead.

Perhaps providentially, as I prepared for this week’s discussion, I happened also to be reading Pope Francis’ encyclical on the environment (Laudato Si — Praise be to you, my Lord). After an introduction cataloging the manifold and potential disastrous effects of the destruction of creation, and an affirmation of the important and central role of scientific research in addressing these issues, the Pope turns to more poetic considerations. He begins to describe his own namesake: Saint Francis.

His response to the world around him was so much more than intellectual appreciation or economic calculus, for to him each and every creature was a sister united to him by the bonds of affection… such a conviction cannot be written off as naive romanticism, for it affects the choices which determine our behaviour. If we approach nature and the environment without this openness to awe and wonder, if we no longer speak the language of fraternity and beauty in our relationship with the world, our attitude will be that of masters, consumers, ruthless exploiters unable to set limits on their immediate needs. By contrast, if we feel intimately united with all that exists, then sobriety and care will well up spontaneously. The poverty and austerity of Saint Francis were no mere veneer of asceticism, but something much more radical: a refusal to turn reality into an object simply to be used and controlled— Pope Francis, Laudato Si'

I think the point Pope Francis is making is an important one. It is not merely about what we know about nature— what it is made up of, how we can use it, how rapidly we are destroying it. It is how we relate to nature, how we imagine it. The poetic shapes the practical. Saint Francis spoke of the sun as a brother and the moon as a sister. Saint Francis’ view of the world was, in a manner of speaking “enchanted,” and the Pope reminds us that “such a conviction cannot be written off as naive romanticism, for it affects the choices which determine our behaviour.” Nature is as ever she was. Our language to describer her has changed, and along with it our relationship to nature itself. Is there a way of out alienation that doesn’t simply fall back on wilful ignorance of (exciting and useful!) scientific discovery or nostalgia for a past we can never reclaim?

This leads to the second theme I want you to notice in this book: kindness.

Kindness has sometimes been relegated to the realm of kitsch “Practice Random Acts of Kindness” bumper stickers used to command (and it’s not a bad suggestion). The Merriam Webster dictionary defines kind as “of a sympathetic or helpful nature; of a forbearing nature; arising from or characterized by sympathy or forbearance.” We tend to think of kindness according to its actions. But the etymological origin of kindness is not action, but relationship. Online Etymology Dictionary writes that the word kind originally meant “‘class, sort, variety,’ from Old English gecynd ‘kind, nature, race,’ related to cynn ‘family’ (see kin), from Proto-Germanic *kundjaz ‘family, race,’ from PIE root *gene- ‘give birth, beget,’ with derivatives referring to procreation and familial and tribal group.” Janet Soskice picks up on this in her beautiful little book The Kindness of God.

In Middle English the words ‘kind’ and ‘kin’ were the same— to say that Chris is ‘our kind Lord’ is not to say that Chris is tender and gentle, although that may be implied, but to say that he is kin—our kind. This fact, and not emotional disposition, is the rock which is our salvation.— Janet Martin Soskice, Kindness of God

God is kind to us because, through Christ, he became one of our kind. God is involved in the business of human affairs. Christ’s disposition of kindness is prefigured in the Hebrew word “hesed,” often translated as “loving-kindness,” a word which, itself, was made up to account for the capaciousness of this little word. The Psalmist writes “The LORD is compassionate and gracious, Slow to anger and abounding in lovingkindness” (103:8). Bound up in this image is a God who is gentle, loyal, generous. Hesed implies a personal love and energetic responsiveness. God responds to us, is in relationship with us. God is not alienated from us.

I think kindness is the opposite, or perhaps more appropriately, the antidote to alienation. To be alienated is to be left outside, to be strange and unknown and to experience others as strange and unknown. Barfield describes this alienation with creation, but we see it in our society too, lonely, angry, and incomprehensible. And in ourselves. We feel trapped outside each other, desperately wanting to be known. We want inside.

In this first chapter, after a dangerous experience which nearly kills him, Piranesi writes in his journal: “The Beauty of the House is immeasurable; its Kindness infinite.” An experience which could have been alienating reveals kindness to him. Why does he interpret this experience, and the house more generally, through a lens of kindness and not alienation? It is something to ponder. Is it possible to recover kindness? To see the world, as Saint Francis did, and as Piranesi does, as our sister? Can we ever escape the “pure cussedness” of modernity? These are all questions worth exploring. But of course, Piranesi is a story not an essay. So you’ll have to read on to find out what insights, or rather what sights (perspectives on the world) it might offer.

I can’t wait to hear what you think!

Reading list:

Owen Barfield, Rediscovery of Meaning and Other Essays (Middleton: Wesleyan University Press, 1985)

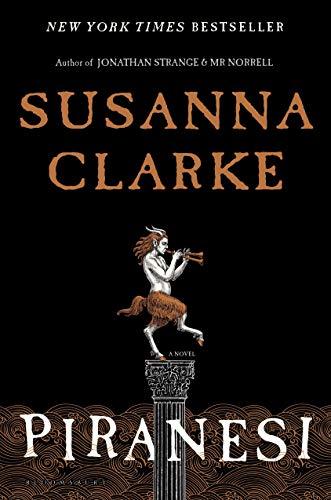

Susannah Clarke, Piranesi, (London: Bloomsbury, 2020)

Pope Francis, Laudato Si’, Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2015, https://www.vatican.va/content/france...

Alison Milbank, Apologetics and the Imagination: Making Strange,” In Imaginative Apologetics: Theology, Philosophy, and the Catholic Tradition, Edited by Andrew Davison (London: SCM Press, 2011).

Janet Soskice, The Kindness of God (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008).

The Book Club — How it WorksI’m excited you’re joining in! This is how it’s going to work: We’ll read one chapter each week. I’ll post a podcast with a friend where we discuss the chapter (this week it’s with my brother Joel!). Then I’ll post discussion questions on Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook, where you can chime in with your ideas, opinions, thoughts and questions. That’s it! That’s all it involves! At least online. I always enjoy the discussions that take place in the comments, but I also strongly encourage you to start a real life bookclub!

Ask a friend to have a coffee and discuss a chapter each week! Have a few friends to your garden! It’s really so much more fun. The other great thing about this book is that it’s only seven chapters (i.e. parts), so it’s a less than two month commitment. Speaking of commitment, the schedule is below.

Book Club Schedule:

June 22nd, Part 1: Piranesi, with Joel Clarkson.

June 29th, Part 2: The Other, with Malcolm Guite

July 6th, Part 3: The Prophet, with Andy, Amy, and Timothy Crouch

July 13th, Part 4,: 16, with Matthew Rothaus Moser

July 20th, Part 5: Valentine Ketterley, with Haley Stewart

July 27th, Part 6: Wave, with Leah Libresco, Caitrin Keiper, and Susannah Black

August 3rd, Part 7: Matthew Rose Sorensen, TBD.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS:

Piranesi has a near death experience with the house, and yet concludes that “the beauty of the House is immeasurable. Its kindness infinite.” Why does he draw this conclusion from such an ambiguous and threatening event? Do you think the house is really kind?

Piranesi thinks he is a scientist. Do you think he is a scientist? In what meaningful ways is he, or is he not a scientist? How does his perspective compare with our own contemporary understanding of the natural world?

Piranesi By Clarke, Susanna Buy on Amazon P.S. additional bookclub!

Piranesi By Clarke, Susanna Buy on Amazon P.S. additional bookclub!As many of you may know, I have a Patreon which has been a great means of support as I’ve finished my Phd. Of course, the Piranesi book club is free and public, but I will also be hosting another, smaller book club on the Patreon which you can join if you fancy also supporting my work with the podcast. In that bookclub we will be reading A Circle of Quiet by Madeleine L’Engle. Last year we read Revelations of Divine Love by Julian of Norwich, One of the reasons that I picked this book in particular is that, even though it was written nearly a millennia later, this book is similar in its motherly, epistolary tone. This book has the feeling of someone writing it exactly to you, to me. And of course Madeleine says that in one of the sections we read this week. That it is personal. Vulnerable. Named. In our present parlance we might even say: authentic.

The book asks: how can we find a circle of quiet? how can we find and keep contact with the essential, the fundamental, the real? how does this nourish our vocation, our writing, our relationships?

I'll do the podcast book club for the $10 tier (podcasts belonging in that tier originally). So if you want to join in (and support beleaguered phd student!) buy the book and make sure you’re in that tier by Monday, June 21st.

Joy Marie Clarkson's Blog

- Joy Marie Clarkson's profile

- 227 followers