Gev Sweeney on Flawed Heroines

from The Scattered Proud

by Gev Sweeney

We like to joke about obsession and blame obsessive-compulsive disorder for everything as destructive as drinking too much to the less damaging, if mildly annoying, twisting of a lock of hair around a finger (my trademark stress reliever). But while obsession is a flaw, it can also be a catalyst for hope, if not outright salvation. Janet Watters, the young heroine of The Scattered Proud, is as messy as a character can get without being addicted to alcohol or any other misuse-able medicinal in vogue in America at the end of the 18th century. Though her obsession can't be seen and is something she hides from others, it governs her life and the lives of those around her.

We like to joke about obsession and blame obsessive-compulsive disorder for everything as destructive as drinking too much to the less damaging, if mildly annoying, twisting of a lock of hair around a finger (my trademark stress reliever). But while obsession is a flaw, it can also be a catalyst for hope, if not outright salvation. Janet Watters, the young heroine of The Scattered Proud, is as messy as a character can get without being addicted to alcohol or any other misuse-able medicinal in vogue in America at the end of the 18th century. Though her obsession can't be seen and is something she hides from others, it governs her life and the lives of those around her.

Janet has been born into a time when people live close to the notion and reality of death and regard it as a necessary, if disquieting, fact of life that compels them to think about their purpose on earth and what will become of them after they die. Their solace – and, often, the foundation of their life's purpose – is religion, in this case the Episcopal Church. Janet's widowed father, a successful and respected lawyer, is on the vestry of St. Peter's Church in Philadelphia, and has cultivated a circle of influential friends that include the church's rector and his family. Though Janet is 13 when the story opens, she's still a very much a little girl, subject to the dictates of her parent and the adults around her. But she has no child's sense of fun or desire to explore the world. She magnifies what should be a child's ordinary lot in life into a continuous exercise in dread. She can't do anything or go anywhere without thinking something dreadful is going to happen to her. And, in an age when girls are raised to become wives and mothers, she disparages herself as unwanted, and foresees a future as a lonely spinster.

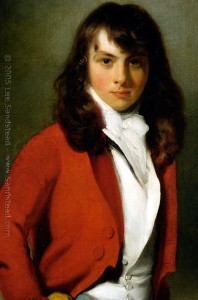

Instead of turning to religion for solace or security, she gleans comfort from the presence of Kit DeWaere, the rector's kindly, understated son who is sometimes the victim of his father's self-importance. Kit believes that doing little or nothing to help people would be an abuse of God's trust in humanity. Incited by a sense of servicehood that wavers between humility and hubris, he surrounds himself with people who, like Janet, are flawed: the beautiful but self-absorbed escapee from the French Revolution who becomes his wife; the mentally handicapped toddlers of the orphanage that houses the secret Episcopal mission he leads in late Revolutionary Paris; the victimized wife and son of a former political prisoner, whose attempts to survive have an unlikely connection to Bonaparte's coup d'etat of November 1799.

Kit himself is flawed. He doesn't know his own limits. He acts expecting the best because he's doing his best, as he thinks God intended, but his good intentions go awry. As the vicar of the church's mission in Paris, he tells Janet, who's been brought against her will to work at the mission: "We all have only one destination, just as we all have only one journey. Everything that befalls us on the road is another blow from the Great Sculptor's metaphysical mallet. It's not a matter of how the blow shapes us, but how we choose to interpret and withstand the blow. Do we allow ourselves to be shattered in pieces, like the proverbial earthen vessel, or do we embrace our circumstances, taking heart from knowing their true source?"

Kit himself is flawed. He doesn't know his own limits. He acts expecting the best because he's doing his best, as he thinks God intended, but his good intentions go awry. As the vicar of the church's mission in Paris, he tells Janet, who's been brought against her will to work at the mission: "We all have only one destination, just as we all have only one journey. Everything that befalls us on the road is another blow from the Great Sculptor's metaphysical mallet. It's not a matter of how the blow shapes us, but how we choose to interpret and withstand the blow. Do we allow ourselves to be shattered in pieces, like the proverbial earthen vessel, or do we embrace our circumstances, taking heart from knowing their true source?"

But when Kit's pregnant wife leaves him, he shows none of the strength his words imply and becomes warped by unspoken despondency. It's not his counsel that resonates with Janet. What resounds is her disappointment in him, and her eventual guilt at that disappointment:

I conceded to myself that I was glad to leave Kit behind [in Paris]. He had exposed himself as one of those people who spout great thoughts and noble acts when all is well, yet crumble under difficulties that demand them to exemplify their own teaching. I conceded but could not believe. I was equally certain that Kit's decline was no mere deficiency of character. It was the creeping decay of self that comes from knowing one has not merely made a mistake, but has lived for a long time thinking all was well. I remembered how, so many years before, he had spoken to me about man's responsibility to use his intellect. Somehow, since then, his own intellect had failed to discern anything about his wife to foretell a withered marriage. He did not know how to live with either himself or the consequences of his error. I should have taken him aside and reminded him what he had said about the Great Sculptor's metaphysical mallet. (…) But I said nothing. And because I said nothing, I fall asleep at night wondering how different everything could be.

Kit's decline is a turning point for Janet. Though she says, "I could do no more than await the further lessening of Kit DeWaere, a collapse I never could have imagined, not even in a fevered dream," she does indeed do more. She continues to dwell upon him. His name and image pervade her interactions with the family who, on Kit's behest, took her in after her father died, and with George Frederick Cunliffe, the haughty, handsome priest sent to Paris as Kit's assistant. From obsession comes strength. When Janet and Kit become trapped in political machinations that never should have been their concern, Kit's fate gives Janet a fresh reason for being. The once-scared, self-castigating child becomes something she never could have imagined of herself: a woman in love with life and the world.

Gev Sweeney has been telling tales since sixth grade, when she was caught daydreaming about a failed jungle expedition. She grew up to become a journalist who did everything from getting caught in a riot to shooting a Brown Bess (not during the riot). She advocates historic authenticity in fiction, but forgives Shakespeare for all those horrid anachronisms in Julius Caesar. She lives at the Jersey Shore with her guinea pigs, Auden and Philip Baby-Boar.

Gev Sweeney has been telling tales since sixth grade, when she was caught daydreaming about a failed jungle expedition. She grew up to become a journalist who did everything from getting caught in a riot to shooting a Brown Bess (not during the riot). She advocates historic authenticity in fiction, but forgives Shakespeare for all those horrid anachronisms in Julius Caesar. She lives at the Jersey Shore with her guinea pigs, Auden and Philip Baby-Boar.

The Scattered Proud is published by PfoxChase Publishing. To find out more about Gev Sweeey, please visit her website.