Cabin Fever in Covid Times – What Can We Learn from Canadian Settlers?

Days are getting shorter, temperature is falling, as winter creeps towards us.

We are a Northern people. Danes have their Hygge, Norwegians their Koselig and Canadians, old and new, have a rich, diverse heritage to draw from. We can take heart, from the ‘lessons learned’ by our Canadian Settlers, draw principles to overcome challenges, and face a long winter, temporarily apart in an imposed COVID-19 isolation.

“…my love for Canada was feeling very allied to that which the condemned criminal entertains for his cell—his only hope of escape being through the portals of the grave. The fall rains had commenced. In a few days the cold wintery showers swept…and a bleak and desolate waste presented itself…”(1).Susanna Moodie’s lament of her first winters in Ontario, 1837, illustrates the struggle of English settlers facing a harsh Canadian winter. They had yet to learn from the Indigenous people, as had French settlers.

During their first winter on American Shores, in 1604, more than half of the French settlement died of scurvy. Another winter loomed. In Spring, their leader, Samuel de Champlain moved the settlers across the Bay of Fundy to the northern shores of Nova Scotia to what was hoped a better site. And he came up with a plan to endure the brutal winter. Believing the fatal illness was the result of ‘idleness’, he established the ‘Order of Good Cheer’.(2)

Modeled loosely on European Chivalry, the Order mandated fellowship and good cheer through weekly feasting and entertainment, from November to March. Through festivities, decorations, competitive hunting and fishing, he hoped to keep spirits up. Each week was hosted by a different member of the more than 30 men in the company, who prepared and planned activities and food. Local Mi’kmaq people were invited who graciously supplied most of the fresh food. The regular feasting fortified settlers’ bodies and minds throughout the long winter. Inclusion of the Native diet greatly helped.

Cedar tea had already been introduced by the Iroquois to an earlier French explorer Jacques Cartier in the winter of 1535-36. Icebound, on the St. Lawrence River, at an Iroquois Village of Stadacona (present day Quebec City), his men slowly succumbed to scurvy.(3) As an offering of peace, the Iroquois Leader, Donnacona, prepared and offered them a tea made from the leaves of a white cedar tree. Preferring to die quickly from poison rather than slowly through scurvy, Cartier drank it and soon felt better. Within 8 days the men were restored.

In the spirit of adventure, however, these later adventurers consumed unfamiliar foods, and participated in outdoor activity with good humor. Adaptation to their New World rather than imposition of expectation contributed to their survival. Mental health improved and bodies strengthened.

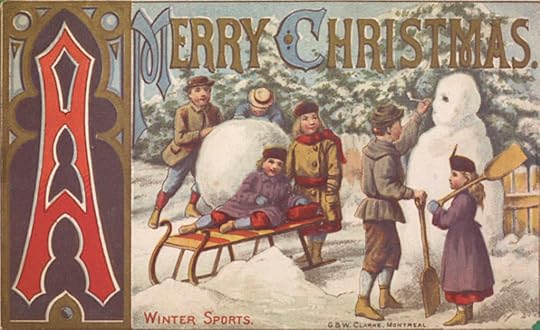

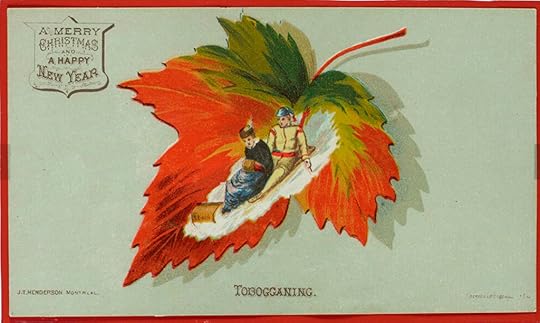

Four winter activities they learned from the Indigenous Peoples are still enjoyed in Canadian Winter.

Hockey: Mi’kmaq skated on animal bones tied to their feet, shooting pucks of frozen apples and sturdy sticks.Tobogganing; Although used to travel and transport across deep snow, toboggans converted to fun on snowy hills.Snowshoeing; design of shoes varied with terrain and First Nation, but allowed freedom amid heavy snowfall.Ice Fishing; First Nation people fished year-round, chipping holes in the ice and dropping down a lure-on-line.

The population of the early French Catholic settlement quickly grew helped by the influx of 500 Filles de Roys (daughters of the King). These were single women of good character, sponsored by the King of France, to marry decommissioned French soldiers and Habitants of the new colony.

The Canadian climate was vastly different from the milder France, but the open-minded settlers adapted clothing and lifestyle to that of the Indigenous people, dressing warmly in mukluks, furs and warm knitted tuques, mitts and scarfs. Colour was vibrant, if only to prevent being mistaken for game in the bush.

Warmly dressed, snowshoed and with toboggans Canadiens moved freely throughout the long winter season. They also retained the Joie de Vie (Joy of Life) attitude of the Order of Good Cheer in both daily life and their faith. French Canadian chapels are a celebration of drama and colour. Icons, relics and stained glass can be gruesome, but rich woods, smells of candles and incense, and hues of blues and shining gold trims warm the soul. While mass was said in foreign Latin, these objects translated faith’s intangibles into the sensory.

Christmas was primarily a religious celebration, in the French colony. Beginning with mass on Christmas Eve, it culminated January 6th, with mass on the Feast of Epiphany commemorating La Fête des Rois—the visit of the Three Wise Men to the Baby Jesus. Within these 12 days, the spirited Canadiens packed a grand season of good cheer.

Upon return from Christmas Eve mass, they held a Réveillons—an all-night “awakening” party—with feasting, toasting, dancing, story-telling and merry-making until dawn.(4) Food was important: Tourtière (meat pie made with pork, beef and veal), Ragout des Pattes de Couchons (tender pigs feet stew), Cretons (spiced pork and lard), roasted root vegetables, Tartes aux Sucre (maple syrup pie), along with generous cups of wines, spirits and beer. This was high-fat feasting that met winter’s demands.

Throughout these 12 days, they visited and gave modest gifts. New Year’s Day was more popular that Christmas, with gift-giving from Baby Jesus (not Santa) and the Head of the household praying a Blessing of Favor over the household for the coming year.

Winter carnivals followed after Christmas, continuing throughout the pre-Lenten season. With hunting and ice fishing competitions, canoe racing across icy rivers (a mix of paddling and foot races over icy hazards), snowshoe races, snow sculpturing the cold and isolation of winter was tamed. Come Spring’s warming, ‘sugaring’ season began, with harvesting of maple sap to be boiled down to rich syrup. Hot syrup, hardened over snow into taffy or poured over grill cakes with beans, was celebrated in winter’s snows.

At Lent, frivolity shut down for 40 days in observance of Jesus’s atonement for sins at Easter. Even that somber week was filled with dramatic rituals, such as ashes worn on foreheads, candlelight church overnight silent vigils and religious parades.

After the fall of French Canada, in 1759, English settlers poured into the now British colony, primarily in the west. Slowly they accepted clothes, diets and customs more suitable, to their new circumstances.

The Scots brought with them Hogmanay(5) traditions to welcome in the New Year. Celebration involved cleaning the house, top to bottom, to ritually relieve its inhabitants of unwanted burdens. At midnight of New Year’s Eve, the first to enter the house—the ‘First Footer’–was welcomed with drink of whiskey. He brought a foodstuff gift, a symbol of blessing to come. Fire (a residue from the pagan pre-Christian origin of the festivity) played a significant part, with either a torch procession, or a grand bonfire.

The English also had their traditions. With the French, they shared an observance of the Twelfth Night. It was not a religious tradition, for them, but a peculiar role-reversal rite.(6) A cake was the center of celebration, with a bean baked in. Everyone partook, with the one receiving the piece with bean was declared royalty for the evening. This role reversal could sometimes play out on grander scale, with cross-dressing and class-lines between servants and masters ignored for the night. The tradition of ‘Servant’s Ball’ was embraced, with masters welcoming the servants into their home for the evening.

The Christmas tree was not yet a part of Canadian culture, only arriving with upper classes during the Victorian Era. But greenery was brought in to cheerfully decorate cabins, filling air with scent. From the end of January until Maudy Tuesday (and the Pancake supper) before Lent, settlers warmed their heart and hearth with festivity, light, and good food. Expectation adapted to their circumstances, as they enjoyed what was readily available—the snows of winter. Old was not thrown away, but retained along with that which bettered their world. They did not just survive, but thrived.

In this time of Covid we also face an uncertain dark winter with isolating physical-distancing and limits on social gatherings. So too, we must adapt, as did these settlers. For urban dwellers this presents a greater challenge than those of spacious suburbia and rural communities. Economics also are a factor, but overcoming principles from the past remain the same: Mental and physical wellbeing are essential.

Food feeds not just the body, but the senses. Use of light to combat seasonal depression is well-documented.(7) Spirituality and faith also contribute positively to mental health.(8) Colour and scent, also. This blog is no substitute for sound medical treatment.

Canadian settlers lived actively, under the winter sun. They enjoyed a simple faith, in good doses, interspersed with festivity and fed the sensory. With an open mind, they changed up roles, schedules, and embraced new clothes, foods and traditions.

Whilst our world is not so simple, we do as those of the Order of Good Cheer, choose our reality and adapt.

Although socially-distanced and masked we can enjoy the outdoors, window-shop under street lights, picnic in the snow, play frozen Frisbee-golf, and ‘toboggan’ on green garbage bags in the winter sun. Ice skating at city parks with second-hand skates, in vibrantly colored Value Village outfits, opens up a new world. Greenery grown in cardboard egg cups on window sills, from tomato sandwich bits, or avocado pits brings unanticipated life. Christmas lights or indoor Fairy lights can stay lit up all winter long.

Sipping maple syrup sweetened coffee, we can write physical letters, phone home, DM comments or Zoom group meals. Though travel is restricted, we can try international take-out foods, learn a few phrases from You-Tube and self-study their history and politics. We can learn to crochet a throw for a care-home, and have a pet guppy or two (same sex), in a fish bowl, join an on-line book club, or passively observe a religious service. We must be open-minded to the possibilities.

Most importantly, we can be kind, not just to others, but to ourselves. These challenging circumstances can be overcome, as others learned before us. We are Canadians.

(1) Susanna Moodie, Roughing It in the Bush; Life in Canada, New Canadian Library@1989, McClelland & Stewart Inc.

(2) The Lieutenant Governor Nova Scotia, FAQ (it.gov.ns.ca) Order of the Good Time. @2015 Province of Nova Scotia.

(3) Nancy J. Turner Indigenous Peoples’ Medicine in Canada, The Canadian Encyclopedia, May 1, 2019

(4) tvo.org, Daniel Kitts, Why French-Canadians kick off Christmas with an All Night Feast, Dec 23, 2016

(5) Barbara Greenwood, A Pioneer Story, @1994, Kids Can Press

(6) Tessa Boase.com, The Strange Ritual of the Servant’s Christmas Ball

(7) Light Therapy, Mayo Clinic, mayoclinic.org

(8) Dr. Deborah Cornah, The Impact of Spirituality on Mental Health: A review of the Literature, mentalhealth.org.uk