Where in the World is the Big Empty?

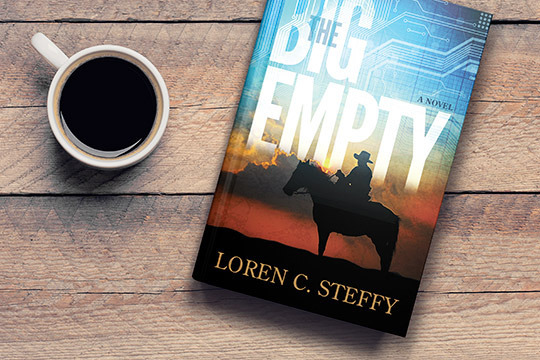

One of the lingering effects of the COVID-19 pandemic is that the printing business has been disrupted significantly. As a result, the release of my novel, The Big Empty, keeps getting delayed. The latest setback was because the printer wasn’t able to get either of the two colors of cloth I’d selected for the binding. So it goes. The good news is that The Big Empty is being printed, it is available for pre-order, and for those who do decide to order it, we will get it in your hands as quickly as possible. In the meantime, here’s an excerpt.

The Big Empty — Prologue (Part I)

A frozen wall of fear hit Trace Malloy seconds before the oncoming truck. The grille covering the big diesel engine filled his windshield. The horn blew a pneumatic wail that plied his thoughts reluctantly, coaxing him out of his reverie too late to turn away. His right hand shot out instinctively to steady his coffee in the cup holder as he pulled hard with his left on the wheel. Both were futile gestures.

The impact snapped him forward, then back again, as his pickup seemed to hop off the ground and bounce into the bar ditch beside the road. The seat belt snapped hard against his sternum. He heard the big truck’s tires lock up behind him as it skidded to a stop. The sound of rubber grinding on asphalt lingered for a moment. Malloy felt his one hundred-sixty-five-pound frame compress into the unforgiving seat, forcing the last bit of air from his lungs. The pickup was suddenly still.

Coffee burned through the leg of his jeans, and his chest felt as if he’d been hit with a two-by-four. He moved hesitantly and was relieved when his body responded with only dull aches. No shooting pains probably meant nothing was broken. He’d likely saved himself the humiliation of explaining what had just happened to Doc Lambeau.

He cursed himself for not paying attention. Looking through the windshield, already cracked before the collision, he tried to orient himself. He felt like a child caught daydreaming in school, his mind racing to catch up with what he’d missed. The bar ditch rolled out in front of him, a partner to the long black line of asphalt on the left, both pulled taut toward the horizon.

He found himself hoping the pickup would still be drivable. He’d managed to swerve enough that the impact must have been a glancing blow. The fact that he was still conscious, still in one piece, seemed to prove that. He’d have to explain how he’d busted up a truck on the open road. The embarrassing truth was he’d just been thinking. Not about anything in particular, he was just letting his mind wander. He’d rolled through his days in Kansas — why they were suddenly in his mind so much he didn’t know — and about Colt’s accident last summer. By the time the truck hit him, his mind had meandered back to its favorite worry — would he and Darla be better off selling out and moving to town or trying to make it through one more year. And if they made it through that one, what about the next one?

His brain had a way of sidestepping when something was bothering him. Instead of obsessing over a problem as some people’s do, his mind tried to distract him by conjuring images from the past. Still, as always, there was a common thread to these random thoughts — Colt’s injury, the family farm, his days in Kansas, Luke’s death. They all led back to the same problem, one that he couldn’t solve. That didn’t stop his mind from revisiting it, even if he was driving down the road and should have been thinking about work. His mother, who never believed in stewing over intractable concerns, would have scolded him if she’d seen how distracted he’d been. “Make your peace with the Lord, and you don’t have to worry,” she’d say. He never found it that easy, peace or no peace. Besides, his mother was usually referring to death. These days she didn’t speak of it anymore, of course. Not now that it was almost upon her, now that it had, for all practical purposes, already claimed her. For that matter, she didn’t speak of much of anything. And if she did, Malloy wasn’t around to hear it.

He tugged on the door handle of the pickup and it opened with its usual hesitation. As he stepped out, he could see the crumpled fender. The headlight was gone, and part of the wheel cover had been pressed down into the tire, puncturing it. He cursed again. Changing it wasn’t going to be easy in the ditch.

“Are you okay?” The question came from over his shoulder. He turned around and looked up from under the red brim of his cap. Years of grime and dirt had obscured the hat’s patch that said “Possum Kingdom Lake.” More than a decade of use had bent the brim of the fishing-trip souvenir into a gentle crescent that cupped his sunglasses. The trip now seemed a lifetime ago, one of the last times he and his brother, Matt, had enjoyed each other’s company, pulling up 30-pound catfish from the depths of the lake itself and later plucking small-mouthed bass from the river below the dam.

“I’m fine,” Malloy said.

The other man stood on the roadside, hands at his waist with the palms turned upward, as if he couldn’t decide whether to shrug or fight. Either way, Malloy wasn’t worried. The man wore jeans and a green shirt with a pale plaid pattern and buttons through the collar points. Underneath, a t-shirt was plainly visible. Both shirts — faded cotton — were tucked neatly into the jeans and secured with a webbed belt. He had on wire-rimmed glasses and his swept-back hair made it look as if he had something stored in his cheeks.

“You swerved right into me,” the man said, his voice rising sharply in the middle of the sentence and falling at the end. “I couldn’t stop. I’m driving that big truck; I couldn’t turn fast enough. I was afraid it’d flip over.”

“My fault. Sorry,” Malloy said, walking up out of the ditch.

He knew he wasn’t supposed to say that. Insurance companies said to never admit wrongdoing. More importantly, he knew company policy forbade it. He glanced back at the damaged fender. If he could pull the metal free of the airless tire, he could probably change the flat and get the truck down to Terry Garrison without having to involve the adjuster that the company inevitably would send out. It seemed pointless to argue over something he knew was his fault. “You mess up, you fess up,” his mother used to say.

The man stared at him for a moment then went on talking as if he didn’t believe Malloy had said anything.

“You were just driving in the middle of the road. I thought you were turning, and as I got closer, you just kept drifting over into my lane. There was nothing I could do.”

“It’s okay. I was just turning into this road here,” Malloy said, pointing to the dirt stretch on the other side of the highway that led to a gate on the Main Ranch. “There’s usually not much other traffic out here.”

“Well, that’s not an excuse…”

“Said I was sorry. Is your truck okay?”

It wasn’t his own truck, of course. Malloy could tell just from looking that the man had never driven a truck before in his life. His claim that he couldn’t swerve belied his inexperience behind the wheel. The big yellow-and-black markings of the Ryder label clinched the theory.

The truck was idling on the east-bound lane, a few feet from the point of impact. Malloy was no traffic inspector, but he could decipher the tell-tale black skid markings that shot out from the back wheels of the vehicle straight as exclamation marks. The truck hadn’t veered from its lane.

For more information on this and my other books, check out stoneycreekpublishing.com