CMP#37 Reading into the Silence

Clutching My Pearls

is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Many modern Austen fans are eager to acquit her of being a woman of the long 18th century. Further, for some people, reinventing Jane Austen appears to be part of a larger effort to jettison and disavow the past.

Click here

for the first in the series. "Why bring the slave trade into the novel at all? And then why, having done so, leave the topic hanging without resolution?

Clutching My Pearls

is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Many modern Austen fans are eager to acquit her of being a woman of the long 18th century. Further, for some people, reinventing Jane Austen appears to be part of a larger effort to jettison and disavow the past.

Click here

for the first in the series. "Why bring the slave trade into the novel at all? And then why, having done so, leave the topic hanging without resolution? -- Tom Keymer, Jane Austen: Writing, Society, Politics (2020) Reading into the Silence: The Trip to Antigua

A West Indian planter In the previous post, we reviewed the “dead silence” passage in Mansfield Park, discussed the conversation it described, and listed numerous examples from scholars and writers who have described the conversation incorrectly.

A West Indian planter In the previous post, we reviewed the “dead silence” passage in Mansfield Park, discussed the conversation it described, and listed numerous examples from scholars and writers who have described the conversation incorrectly.Whether the critics (correctly) refer to the “dead silence” that falls after Fanny asks a question about the slave trade and her uncle replies, or whether they incorrectly relate that Fanny asked a question which her uncle didn’t answer, the conclusions vary wildly. The “dead silence” passage is used to prove that Austen didn’t care about slavery, or didn’t care enough about slavery, or cared passionately about slavery.

Today, we are more apt to read analyses of Mansfield Park which claim that far from ignoring slavery, the book is entirely about slavery, colonialism and empire. As Claire Harmon wrote in Jane's Fame, a history of Austen’s rise from moderately successful author to world icon, “Elements in the novel that hardly seemed to be noticed before by critics... have subsequently become, as Rajeswari Sunder Rajan has pointed out, the ‘locus of the novel’s meanings.’" And as Tom Keymer writes in Jane Austen: Writing, Society, Politics, “It has become a novel about offstage episodes and unspoken themes; global rather than domestic.”

Creepy Sir Thomas and defiant Fanny in the 1999 movie adaptation What are we to read into the "dead silence"? What do you read into the silence when you're hoping for an answer to an important message? You try out various hypotheses, some technical, some benign, some ominous, depending on your turn of mind. Perhaps they didn't get the message. Perhaps they missed it. Perhaps you offended them somehow. Perhaps they're busy. Perhaps they're ill. Perhaps…. the thing is, you don’t know. But we all read into the silence.

Creepy Sir Thomas and defiant Fanny in the 1999 movie adaptation What are we to read into the "dead silence"? What do you read into the silence when you're hoping for an answer to an important message? You try out various hypotheses, some technical, some benign, some ominous, depending on your turn of mind. Perhaps they didn't get the message. Perhaps they missed it. Perhaps you offended them somehow. Perhaps they're busy. Perhaps they're ill. Perhaps…. the thing is, you don’t know. But we all read into the silence. Some scholars possess the ability to interpret the emotional colouring of the "dead silence" passage, yet they arrive at different interpretations. For one author, it’s “Fanny's timid question in Mansfield Park,” for another, it’s “Fanny Price's outburst about the treatment of slaves,” for another, Fanny "bravely makes her abolitionist sympathies clear."

Others have explained the Bertrams' silence as “ambivalence,” “guilt,” or resentment that Fanny would pick such as “ill-chosen topic” that is “too close to the bone.” Some examples: “the “dead silence” of Fanny’s Bertram cousins at her question about the slave trade illuminates the Bertrams’ familial ambivalence to the domestic implications of abolition.”“[T]he Bertrams, acutely aware that they owe their elegant lifestyle in England to the exploitation of slaves in the sugar plantations of the West Indies, reveal their collective guilt in the ‘‘dead silence’’ that follows Fanny Price’s awkward question about the slave trade.”“An ill-chosen topic; she is not yet quite brash enough to pursue it: “there was such a dead silence!”’The "dead silence" that follows Fanny's question about slavery on Sir Thomas's return from Antigua is, for Southam, full of meaning: in "the autumn of 1812, the 'slave trade' was still a topic too close to the bone for a plantation-owning family [such as the Bertrams] to discuss freely and openly."

Bernard Hepton as Sir Thomas in the 1983 adaptation The “dead silence” of the cousins could be indifference, inattention, or guilt. But as previously mentioned, the idea that the "dead silence" means the topic of slavery was too sensitive for the Bertrams to discuss is simply not historically accurate. Sir Thomas had been a Member of Parliament, where the topic had been debated during the proceeding decades. There was abundant public commentary and published writings on the slave trade, slavery, sugar, and the West Indies at this time, all presenting different aspects of the issue and different opinions. More on that later.

Bernard Hepton as Sir Thomas in the 1983 adaptation The “dead silence” of the cousins could be indifference, inattention, or guilt. But as previously mentioned, the idea that the "dead silence" means the topic of slavery was too sensitive for the Bertrams to discuss is simply not historically accurate. Sir Thomas had been a Member of Parliament, where the topic had been debated during the proceeding decades. There was abundant public commentary and published writings on the slave trade, slavery, sugar, and the West Indies at this time, all presenting different aspects of the issue and different opinions. More on that later. Therefore, Austen could have been more explicit -- if she had chosen to be.

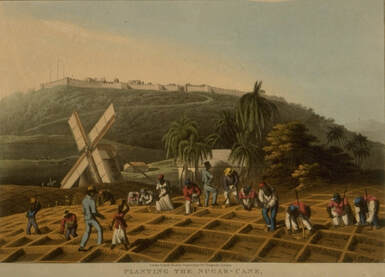

Planting Sugar Cane, Antigua It is rather remarkable, but undeniable, that none of the references to Sir Thomas's trip to Antigua mention slaves or betray any kind of self-consciousness about slavery. The references are focused on Sir Thomas -- his finances, his health, his safety and well-being. After his return, the few final references focus on the modes of living of the planter class, what Austen would call the "manners" of the West Indies.

Planting Sugar Cane, Antigua It is rather remarkable, but undeniable, that none of the references to Sir Thomas's trip to Antigua mention slaves or betray any kind of self-consciousness about slavery. The references are focused on Sir Thomas -- his finances, his health, his safety and well-being. After his return, the few final references focus on the modes of living of the planter class, what Austen would call the "manners" of the West Indies. Mrs. Norris talks about the "Antigua estate" making "poor returns." Sir Thomas's activities in the West Indies are only ever described as “his business” or “his affairs." Austen describes the length of his absence and reminds us of the danger of the voyage there and back again. When he does return, we are told he regales the family with tales of the West Indies. But apart from a mention of balls and dancing, there are no details.

His oldest son Tom had nothing to say on the subject of Antigua, except for suggesting that the dangerous return sea voyage their father must make, was a good excuse for putting on a play to ease their mother's supposed anxiety -- a suggestion that comically backfires when Edmund and Tom turn to see her dozing on the sofa.

We are told that when Sir Thomas returns, Fanny looks at him with tender sympathy, because he is haggard and has obviously suffered under the West Indian climate.

The focus throughout is the dangers and sacrifices that Sir Thomas undergoes, not the sufferings of the enslaved persons who, unlike their master, made the Atlantic Crossing stowed below decks in chains.

Overall, Austen gives us just enough detail to usher Sir Thomas off the stage when his absence is necessary for the plot, and to bring him back again when his presence is necessary for the plot. The word "sugar" does not appear in the book and "plantations" refers to the cultivated ground in Mansfield, not Antigua. Apart from worry over Sir Thomas, the other emotion expressed in relation to Antigua is pleasure. Sir Thomas’s answer to the slave-trade question gave Fanny “pleasure,” while he would have been pleased if she'd asked him more questions. As well, Fanny says, “I love to hear my uncle talk of the West Indies, I could listen to him for an hour together.” Sir Thomas "is disposed to be pleased with [her] in every respect."

How to reconcile Austen's emphasis on pleasure with the assertion that there is a daring but long-overlooked anti-slavery message in the novel? There is no hint that Fanny is accusing or badgering her uncle when she asks him about the slave-trade, though modern critics have inserted that inference. She is not the Regency equivalent of the vegan granddaughter lecturing everybody at Thanksgiving. Clearly Fanny is not listening to his information with horror or disapproval. How to reconcile this with the idea that Fanny challenges Sir Thomas?

One interpretation that I find very plausible, neither condemns Austen as indifferent to slavery nor builds her up into an abolitionist Total Badass. It is a more nuanced interpretation based on the slavery debate as it was waged in Austen's time.

To be continued. James Stephen (1758 - 1832), a lawyer, legislator, and abolitionist with a pretty amazing personal backstory, makes an appearance in My Mansfield Trilogy. Click here for more about my books.

Published on April 11, 2021 00:00

No comments have been added yet.