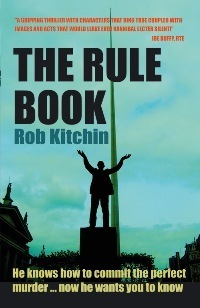

Review of Rob Kitchin's THE RULE BOOK

The Rule Book is an intricately plotted police procedural set in and around Dublin, in the atmosphere of impending social and political failure that eventually led to the Celtic Tiger having its head unceremoniously expelled from its ass by the 2008 banking crisis.

The book was published in 2009, but Kitchin's 'Acknowledgements' on the final page are dated August 2008. Thus, he was probably writing the story in 2007 and the beginning of 2008. The novel shows how contemporary crime fiction, as opposed to historical crime fiction--which has the benefit of hindsight--can, in the hands of a prescient writer, capture the most salient elements of a corrupt state, although at the time of writing the writer doesn't know what is going to happen in a few months' or a few years' time.

Detective Superintendent Colm McEvoy is put in charge of the hunt for a serial killer who, after every murder, leaves behind a deliberate set of clues, but in never enough detail--until it is too late. McEvoy is a decent man, a person whose human failings are numerous, and whose grieving for his dead wife, prevents him from functioning effectively, either as father or policeman. These traits reminded me of the police officers to be found in the crime novels of Henning Mankell and Arnaldur Indridason. A big difference between Kitchin and Mankell or Indridason is that Kitchin refuses to tie everything up neatly with a pink bow at the end of the book.

You want Colm McEvoy to succeed but, at every turn of Kitchin's cruel handling of him, he screws up even worse than the time before, and the reader becomes more and more convinced of what McEvoy admits himself, that if the killer is ever unmasked it will only be by accident. Kitchin invites you to to witness McEvoy being used as a convenient scape-goat by his superior, a commanding officer who says he is there to protect him but who is, in reality, a cynical placeholder. Time and again, McEvoy is taken off the case, only to be put straight back on it, as his commanding officers (his boss and his boss's boss, right up to the Minister for Justice) realize that, if they no longer have a fall-guy, they will have to take the responsibility for failure themselves. Colm McEvoy is also undermined throughout the book by a Detective Inspector named Charlie Deegan, who brought to mind the way in which another self-serving Charlie, who went under the surname of Haughey, undermined the then solid underpinnings of the Irish State with which he was entrusted. Deegan's conduct, undermining Colm McEvoy at every opportunity, gets him taken off the case, once, but people in positions of power are ready to pull strings to reinstate him, and he too is kept on until it is too late.

Kitchin's descriptions of the hounding of Colm McEvoy and his family, by journalists from the Sun, and the influence the press had on figures of power in Ireland (terrified of having people from abroad scrutinize their incompetence) foreshadows the well-deserved wave of public disgust in the U.K. that was soon to hit News International and all who sail in her.

Kitchin dissects an Ireland where men who get into positions of power--shown here in the shape of the country's police force, but not limited to them--suffer from a lack of expertise in a field they are supposed to master; spend an inordinate amount of time trying to please the media; and pay more attention to form than substance. Colm McEvoy's boss is more interested in the state of his clothes, and how he will appear to the television cameras at the frequent press briefings, than he is in the details of the murders McEvoy has to investigate. People in authority refuse to shoulder the responsibility that should be the corollary of their well-paying jobs; push important decisions down the chain of command until they find the guy who will take the fall; plan every action in the way that will best cover their asses, and, most tellingly of all, have no idea of what needs to be done to thwart sophisticated enemies, whether they be serial killers, (or, by extension), financial whizz-kids, who are left free to run rings around the stately, plump, prevaricating authorities.

Through the prism of the Irish police force, the novel depicts a whole country that doesn't have the smarts to understand any of the challenges it has brought on itself by moving away from a rustic set of values towards items of interest dear to the gutter press: sensationalism, human weakness, the wreckage resulting from the availability of cheap and plentiful booze and drugs and the rivers of teenage vomit and drunken violence running through Dublin's O'Connell Street late on a Saturday night.

The novel points out that there has never been a serial killer in Ireland. Until four years ago, the Republic of Ireland had also not had a banking crisis that beggared belief when it happened, but for which all the signs and clues had been there for perspicacious economists like Morgan Kelly. Morgan Kelly, a man who specialized in the economics of Medieval Iceland, realized what was about to hit Ireland when he discovered, nearly by accident, that neither the Banks nor the Government were following their own basic economic rule book.

Colm McEvoy, in some ways, brought to mind the tragic figure of Brian Lenihan junior, the Irish Minister for Finance, and especially the night he was left alone to fend for himself, a distraught figure wandering the back roads of Ireland, charged by his political, banking and property-developer masters and colleagues to find a silver-bullet solution to the Irish banking crisis, a fall guy who was immediately blamed for the only remedy he could find, the disastrous state guarantee of the Irish Banks.

At the time of the novel, McEvoy is shown as a symbol of the decent people who were trying to hold Ireland together in face of an unprecedented assault on its identity. Too busy at work to get a regular wash, in dire lack of sleep, wearing a disheveled suit, now two sizes too large for him since he began to grieve for his late wife, he is obviously not up to the job he eagerly takes on. All he has going for him is a basic level of competence and a streak of honesty, but he is no match for the evil mind of the sophisticated killer, who spies on him and taunts him with clues which will eventually show that the center of everything rotten lies in what has constituted a pillar of the Irish State, ever since its founding: Maynooth.

Rob Kitchin leaves the reader with the feeling that what he or she has understood is pretty bad, but worse is still to come. Any other mind like the serial killer's--determined, sophisticated and evil--will also be free to run rings around the plodders to whom it arrogantly gives all the clues. The authorities will be incapable of catching the most powerful criminals in their midst, even when the wrongdoers disregard their own rules and make basic mistakes or, as the serial killer does at one moment, hold the door open for them while wearing a ridiculous disguise.

The book is a page-turner and will give any discerning reader of crime fiction extremely good value for his or her money.

Published on February 20, 2012 09:09

No comments have been added yet.