STUDYING WITH ANNE AND WEBSTER. Extract from “Sweethearts of Song (Volume 2) Chapter 7”.

On 17 October 1960 an article appeared in the StoepTalk column of The Star about an unknown singer called Charlie Eastwood who turned up late at a talent show in Bloemfontein. He begged the compère of the show to give him a chance to sing. The compère said firmly that he was too late to enter the competition, but the audience cajoled him into letting Charlie have his chance on stage. They were not disappointed by the beautiful singing. Charlie was obviously the clear winner of the contest. Charlie turned out to be Webster Booth, who was in Bloemfontein for a production of The Mikado. It was at that time that I wrote to them to enquire whether I could have lessons with them when I finished school at the end of the year. I was too shy and unsure of myself to ask about singing lessons so suggested that I could study “stagecraft” instead.

Extract from my 1960 diary:

4 December. Come home with Wendy Scott-Hayward, feeling rather sad about leaving school. When I arrive, Mum phones and tells me she phoned Anne Ziegler! Says that Anne was charming and I have to go to see her on Thursday evening. I am thrilled. Mum says Anne Ziegler was very friendly and conversation went more or less like this:

M. I understand, you run a school of Singing and Stagecraft. My daughter is interested in doing drama.

A. Oh yes, speech training. How old is she?

M. 17.

A. Oh lovely. What’s her name?

M. Jean Campbell.

A. Oh, what a lovely Scots name!

They go on to make an appointment. I have to go at 5.30 to the studio on Thursday. I’m so nervous!

8 December.

I meet Mum in the Capinero restaurant and we have something to eat which I can hardly digest owing to extreme excitement, and then we proceed to Polliacks building and go up to the eighth floor on a horrifying lift. When we arrive outside the studio we can hear a girl singing so we wait till the singing stops before we knock. Anne comes to the door herself and is very bright with gingery-blonde hair, big blue-green eyes with lots of eye make-up on, wearing a striped dress. She is taller than I imagined her to be and she says, “Oh, please take a seat in there,” pointing to a kitchenette with a washbasin. “I”ll be with you in a minute.” We sit in the kitchenette and listen to her teaching the girl to sing. Anne has a strong, purposeful voice with a touch of English accent. She’s from Liverpool originally but it doesn’t sound as though she has any traces of a Liverpool accent.

Studio in Pritchard Street, eighth flooir of building on the right.

Studio in Pritchard Street, eighth flooir of building on the right.After fifteen minutes the girl leaves and Anne takes us into her large studio which has a grand piano at one end, a big mirror at the other and a divan (converted into a studio couch) against the wall. On the wall behind the studio couch are photographs of her and Webster in different shows, featured with various celebrities, and an excellent cartoon of him.

She apologises for keeping us and says that her husband is in Port Elizabeth at the moment, so she has to cope alone. She says, “He’s singing Messiah tonight and it will be broadcast on the English programme”.

She asks what I want to do and I tell her “Drama,” and she asks, “Will I have to get rid of a dreadful South African accent?” I say that I am from Scotland and she says, “Yes, I think you have more of a Scottish accent than a South African one. You have a really good Scottish background.”

We discuss suitable times for lessons and she says, “Next week I”ll be rehearsing like mad for my play at the Playhouse and I don’t want to mess you around, so can you start the week before Christmas?”

I say yes, any time, then she looks up her appointment book and asks if Thursday 22nd would suit. “Yes, certainly.” She says that she finds it difficult to get S Africans to sound “h” as in hark and that vowel sounds are difficult. She tells me that singing is merely an advanced form of talking – merely!

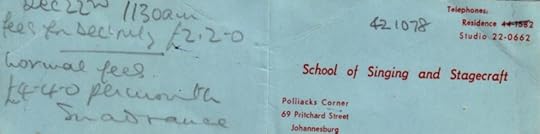

] Anne Ziegler studio fees

Anne Ziegler studio fees

We get up to depart and she says to me suddenly, “You’ve got a lovely face.” I nearly faint on the spot. Mum says archly, “She doesn’t think so.” Anne stares at me and says, “0h, but she has, and a lovely smile too. Make the most of it!” Oh, brother! She apologises again for keeping us waiting and wishes us goodbye. She’s a honey!

I’ve never met or spoken to anyone as famous as that before and I thought I should be frightfully nervous and that she would be snooty and standoffish, but truly, I felt at home with her. My heart didn’t jump wildly in my mouth as it has done for lesser people. I’m sure I shall get on very well with her. She tells me to bring a Shakespeare and poetry, so here’s hoping. Perhaps this is the start of something new. All I can say is, that Anne Ziegler is a regular honey.

22 December. Go into town in the morning and get Gill Mc D on the tram and it feels like old times – drama groups etc. We talk of the theatre. She tells me that Percy Tucker says that people with clean minds book for Jack and the Beanstalk whereas the dirty-minded book for Lock Up Your Daughters!

Go up to Polliacks eighth floor (trying to tell this impartially) – knock at the door about a dozen, times but there is no answer: Begin to feel furious and ready to scream with wrath when suddenly Webster appears, armed with briefcase and wearing a white light-weight sports jacket.

He looks at me quizzically and I say that I am meant to be having a lesson. He is still completely mystified but quite charming. He takes me in and apologises for being late – traffic was so bad. He then goes into the little office and looks up his appointment book and comes out looking rather frustrated and tells me that my lesson is down with his wife and she didn’t come in this morning.

I look at him rather coldly and he tells me that she’s in a play, you know. Yes, I do. “Well, last night it went very badly and she is in a real fandangle about it and has to go to an extra rehearsal in the afternoon and is most upset. She did mean to come into the studio in the morning but because of the rehearsal in the afternoon she didn’t.”

He will phone her. I hear him talking to the maid, “Hilda, is the madam in?”

Evidently the madam is not in so after great confusion over finding telephone numbers, he phones Heather MacDonald-Rouse and says, “Oh, Heather, is Anne there?”

Apparently Anne is there for they have a conversation and he does not seem exactly pleased with her. He comes out and says, “Anne just doesn’t know what to say, she’s so ashamed!” He asks if I could come next week and says, “I’ll make a big cross next to your name for next time.” Naturally, I have to agree and he asks if I came from far.

I say, “Not particularly far,” rather dryly. He apologises once again – more apologetically than ever – and says that he would take me himself but he is frightened that Anne would not approve of what he might give me. He is, on the whole, quite charming and genuinely upset about his wife’s behaviour, but I am very disappointed. I can’t help it – I just never thought that she would forget about the lesson!

However, I have met Webster so that’s something. He is very nice, with rather a red face, and his speaking voice is beautiful – just as it is when he speaks over the radio.

I eventually began my lessons with them the following week. At the time, Webster was fifty-eight, Anne fifty, while I had recently turned seventeen.

Webster was tall and dark, still with a good head of hair which was going slightly grey at the temples. He sported a small moustache and had a disproportionately large nose.

“Hatchet faced, like all my relations,” he once growled, referring to his “conk”, as he always termed his nose.

He was quiet and reserved, not really the temperament one might have expected of an entertainer. Many times I saw him literally pull himself together to put a good face on it when he had to meet new people or do something he was not keen on doing.

At fifty, Anne seemed youthful in comparison to Webster. She was tall and regal with a good figure, classical bone structure, aquamarine eyes, and a rose and white English complexion.

When she was in a good humour, she made everyone feel wonderful, but her moods occasionally blew from hot to cold. When one thinks of the tremendous upheaval they had both suffered in coming to South Africa, one could hardly blame her for occasionally feeling less than cheerful.

Anne had more energy and aptitude for teaching singing than Webster. She had worked hard to cultivate her voice, while he had a God-given voice, even as a child chorister at Lincoln Cathedral. He could not understand why lesser mortals who were not blessed with his perfectly placed instrument, needed to sweat blood to achieve a modicum of success. Anne always said that things had come far too easily to Webster. They had a number of good singing students, but there were others with lesser talent, who were there because they were curious about their celebrity.

While I was studying with them they continued their theatrical and radio work. Anne was playing Mrs Squeezum in the musical play, Lock up your daughters at the end of 1960, with the incongruous song, When Does the Ravishing Begin? to sing – a sea change from We’ll Gather Lilacs or Only a Rose. The show was not a success. Johannesburg was not yet ready for a bawdy Restoration musical.

The Johannesburg Eisteddfod was held around Easter each year. On Easter Monday of 1961 my father and I went in to the Duncan Hall where I bought a season ticket to the Eisteddfod, hoping to benefit from hearing the singing of other students. We stayed for an hour or two to listen to some of the competitions. As we were leaving, we discovered Anne and Webster, sitting further back in the auditorium.

Anne was there to play for one of their students and looked very pretty in a bright floral dress. Her face lit up when she saw me and she said, “Why hello, Jean, how are you?”

Webster turned round to greet me and I introduced them to my father, who said, “It’s a privilege to meet you,” when he shook hands with them.

At the time I thought my father was a bit over the top in his response to them, but he had heard their singing in the UK when they were at the pinnacle of their careers and knew their true worth.

During 1961 Webster presented a programme of oratorio, opera and operetta on the English Service called On Wings of Song and I listened to this without fail every week. During the programme he told the story of his own career and interspersed the tale with appropriate music, including many of his own recordings.

Eventually they heard my singing voice and were happy to change my lessons from drama to singing. Despite my diffident nature, my singing lessons were going well and I worked very hard to please them.

At the time I was singing various Schubert songs in German. Webster said at one lesson, “Honestly, Jean, you’ve got a wonderful memory – of German too. If I had a memory like yours I could really do wonders!”

I smiled at his remark and he added, “But Jean, I wish you’d smile like that when you sing: you’ve got such a lovely smile.”

In the middle of the year Webster went up to the (then) Salisbury in the (then) Rhodesia to adjudicate at the eisteddfod there. Anne joined him at the end of the eisteddfod to give a concert, but they both caught ‘flu. Anne spent most of her time in Salisbury in bed, but she still managed to sing at the planned concert.

Webster appeared as the eponymous prawn in The Amorous Prawn with Joan Blake and Simon Swindell in the latter part of 1961. The distinguished critic at The Star, Oliver Walker, said of Webster, “Playing a straight role with no top notes to sing, Webster Booth shows a suave sense of timing that accords well with his monocle”.

The play opened in Johannesburg and later transferred to Durban. It was very popular. We enjoyed the show although we had to wait until the Third Act for Webster’s appearance.

I was in the middle of my lesson one afternoon when Lucille Ackerman and her family arrived for her audition with Anne and Webster. She was nineteen years old, a year older than me, with a remarkably mature and pleasing soprano. I felt vocally inadequate when I heard her voice. She had spent the previous year at home recuperating after an illness, on the family farm near Piet Retief. Hendrik Susann, the well-known Afrikaans bandleader and violinist lived on a neighbouring farm, and had already featured her as a singer in some of his band’s broadcasts on the SABC.

I had been learning with Anne and Webster for nearly a year when they suggested that I should audition for the newly resurrected SABC choir. Three hundred people auditioned, but only a hundred were accepted. So with some trepidation, not fancying my chances, I went to Broadcasting House in Commissioner Street one Saturday morning to audition for Johan van der Merwe, the choir master. He was an affable dapper young man, only seven or eight years older than me. He took me into one of the smaller studios, where I sang for him and did some rather tentative sight singing tests. I was delighted when he told me he would be pleased to have me in the choir as an alto.

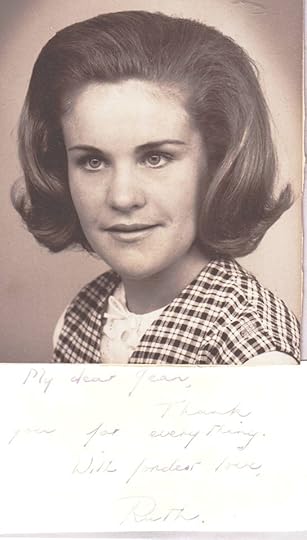

Anne and Webster told me to look out for another of their young students, a girl called Ruth Ormond, who was already singing soprano in the choir. I would recognise her by her piercing blue eyes and honey coloured hair. Anne said she was a hard worker and very intense about her singing. When I met Ruth at the interval of my first rehearsal, she said that Anne and Webster had told her that I was tall, dark and serious looking, and they were very fond of me.

From then on we sat together during the choir break and regaled one another with tales about our lessons with Anne and Webster. We were both originally from Glasgow; we loved singing; and we adored Anne and Webster, the way the majority of our friends adored the latest pop singers like Tommy Steele, Cliff Richard and Elvis Presley. But we were in the lucky position to interact with our idols when we went to the studio for our lessons.

She was a year and a half younger than me, still at Parktown Girls’ High, a short plump girl with deep-set blue eyes. She was outwardly confident, brave and full of fun, with two older sisters, while I, an only child of elderly parents, was shy and diffident, taking a while to warm to strangers. Although we had contrasting personalities, we immediately became the greatest friends.

Ruth Ormond.

Ruth Ormond.In 1962, her family fortunes changed for the better when her mother won ₤40 000 on the Rhodesian Sweep. It doesn’t sound like a fortune today, but in 1962 it seemed like untold riches. Her parents celebrated the win with a trip back to Scotland, the purchase of an imposing black Rover car, and the installation of a kidney-shaped swimming pool in the back garden of their Parkwood home.

I went to her house in Torquay Road to swim in the new pool and she visited me in Juno Street, Kensington where we spent our time singing solos and duets to my piano accompaniment, reading aloud extracts from plays, and sometimes recording our efforts on the Philips reel-to-reel tape recorder my parents had bought me to help with my singing studies. Although we lived a fair distance apart, we made up for the distance by speaking on the telephone for hours on end, in the days when a call, no matter how long, cost no more than a tickey (threepence) a time.

At the beginning of 1962, when the copyright on W S Gilbert’s words ended, Webster presented a Gilbert and Sullivan programme on the English Service. He reminisced about his days in the D’Oyly Carte Company, and played the operettas in chronological order. Up to that time it had not been possible to play any recordings with Gilbert’s words on the radio, so although I recognised some of the music, I found it interesting to be taken through the operettas each week and get to know and like them.

Anne and Webster were producing The Vagabond King at Springs and held auditions for the show on April 26. Earlier in the year Webster took the small part of the doctor in The Andersonville Trial where he had to sit on the stage for over two hours watching proceedings, with only a few lines to say. On the day I went to the matinée he caught sight of me in the audience and amused himself by giving me secret glances from the stage. My piano teacher, Sylvia Sullivan, saw the show and remarked to me, “Such an insignificant part for such a great man.”

After The Andersonville Trial finished – “I’m out of jail at last,” said Webster – he presented another radio series on the English Service called Drawing Room. The idea was to create the atmosphere of a polite middle-class Victorian or Edwardian drawing room concert, where singers and instrumentalists performed their party pieces like In a Monastery Garden, The Maiden’s Prayer, O Dry Those Tears and the like. Sounds of polite conversation and laughter between the items, with restrained applause for the musical offerings were required, so a studio audience was invited to provide these “noises off”.

For the first recording, Webster invited pupils and friends to form part of the Drawing Room in one of the recording studios at Broadcasting House. Ruth and I were there with our parents and we noticed Lucille, accompanied by a large family contingent.

Anne and Webster looked particularly glamorous for the occasion. Anne was wearing a beautiful evening gown, her fair hair in a chignon, while Webster was in full evening dress, to act as compère for the evening and to sing some drawing room ballads into the bargain. The accompanist for the series was Anna Bender, the official accompanist for the SABC. Anne and Webster received their guests graciously. Anne told Ruth and me to save her a seat in the front row, where she sat between us and played her full part in chatting to us between the items on the programme to evoke the atmosphere of a drawing room at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Over forty years later I still remember Miss Rita Roberts (soprano) singing Christina’s Lament to the tune of Dvorak’s Humoresque, Mr Walter Mony (violin), Miss Anna Bender (accompanist) and finally Webster himself, aged sixty, but still in fine voice singing The Kashmiri Song, The Sweetest flower that blows, Parted, O Dry Those Tears and finally Had you but known with violin obbligato by the excellent Mr Mony, a French Canadian, who became a professor and head of the music department at the University of the Witwatersrand.

Ruth and I were entranced to have spent such a happy evening. As we were leaving I told Anne breathlessly that Webster’s singing was wonderful and she replied, “Yes, we’re both very proud of him, aren’t we, darling?” which made me feel rather naïve and childish although I was all of eighteen.

The Drawing Room series was recorded over a number of weeks and we attended another recording when Anne, in a sleeveless black evening dress, sang If No One Ever Marries Me, The Little Damozel and the Handel aria, He’ll Say That For My Love. Later in the programme she and Webster sang duets together: Drink to Me Only with Thine Eyes and The Second Minuet.

The Drawing Room. SABC (1962)

The Drawing Room. SABC (1962)One evening Ruth and I were at choir practice and she decided that during our interval, we should go to the Drawing Room studio to say hello to Webster during the break in his recording session. He appeared delighted to see us and kissed us both. He asked what we were doing there, and then said, “Oh, of course, you’re working aren’t you? It’s a pity you can’t stay for the next recording to hear the wonderful trumpeter.”

Ruth was so excited at meeting Webster that she walked into the men’s cloakroom instead of the women’s, only to have him politely point her in the right direction. We were both blood red with embarrassment by the time we got back to our seats at our now rather tame choir practice.

1962 was an exciting year for the SABC choir. Igor Stravinsky, aged eighty-two, came out to the country with his wife and his amanuensis, Robert Craft. The choir was singing Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms. Professional singers were invited to take part to boost the choir, and my piano teacher, Sylvia Sullivan, and her friend, Jossie Boshoff, the wife of the SABC conductor Anton Hartman, joined the choir for the occasion. Webster had also been asked to sing, but he was insulted that they expected him to do this without a fee and refused. He had also been invited to sing in the choir at the Coronation of Elizabeth II in 1953, but had turned down this invitation too, for the same reason.

At the time of Stravinsky’s visit Webster was having a bad time with toothache. He thought a few whiskies and soda would sort it out, but the pain persisted so he had to have the offending tooth removed. By this time an abscess had developed and this caused him a lot of discomfort. He was given a penicillin injection, but he felt too weak to come into the studio so Anne had to cope with all the students on her own.

The Stravinsky concert was memorable. Robert Craft conducted the first half of the concert, including the Symphony of Psalms. In the second half Stravinsky conducted Fireworks and Petrouchka without a baton, but with a score in front of him. At one point he lost his place in the score and had to search for it again, but the orchestra continued regardless. There was a huge ovation for him at the end of the concert. As we were leaving the hall we noticed Percy Tucker, the director of Show Service, the ticket agency, with the famous British actress Flora Robson and a party. Anne had listened to the concert at home, and while she thought the choir did very well, she admitted that she preferred music with more melody.

During that year I met another of their students, an Afrikaans girl called Roselle Deavall, who lived quite close to me. I had heard her singing during her lesson before mine. At fourteen she had a remarkably mature voice. She was at Queen’s High School and visited me several times. Unlike Ruth and me she was very confident of her vocal ability. I still have a recording of her singing The Mountains of Mourne, complete with Irish accent. She stopped lessons with Anne and Webster until she finished school. After school she went back to them but did not remain with them for very long. In 1965 Webster told me that she had left because she did not think they could teach her anything more. When I returned from England in 1968 I heard that she was singing with the Performing Arts Company of the Free State (PACOFS).

Towards the end of June Webster was booked to go to Bulawayo to adjudicate at the music festival there. The day after Anne’s fifty-second birthday, 23 June, he caught a bad dose of ‘flu and had a temperature of 102 degrees and had difficulty in breathing.

Ruth went to their house on Sunday evening to return some records they had lent her. She had been singing in the choir at St Francis’ Church, Parkview, and was still in her choir robes. She persuaded Anne to let her see Webster, who was still in bed with the ‘flu. She was shocked at his unkempt and pale appearance. He was very ill indeed, with numerous pills and potions on his bedside table, looking quite different from his usual well-groomed self.

Despite his illness he insisted on leaving for Bulawayo the next day as planned. Four days later he collapsed with further breathing difficulties and a temperature of 103 degrees. He had to be flown back to Johannesburg prematurely and was seen by a specialist, who ordered various blood tests to be done. The blood tests revealed that there was too much sediment in his blood. The medics thought he might have contracted a rare tropical disease so he was admitted to an isolation ward in the Fever Hospital in Braamfontein. Anne was not allowed to visit for fear of contracting a disease. All she could do was wave at him through a glass partition.

Much later, after he had undergone many medical tests and suffered some indignities in the process, it was discovered that he had contracted a virus which had led to myocarditis, which caused severe damage to the membranes of his heart. He was in a very bad way and we all feared that he might die.

He seemed to improve and was discharged from hospital for a week or so, but the virus flared up all over again, and so he was once again readmitted to the Fever Hospital. Thankfully he eventually recovered from the debilitating illness, although he was very weak and was away from the studio for several months.

Because of his illness he was unable to record the Gilbert and Sullivan programmes for some time. It fell to Paddy O’Byrne, the worthy winner of The Voice of South Africa competition, to read Webster’s scripts. Paddy O’Byrne was a fine broadcaster and had a wide musical knowledge. He continued as a broadcaster with the SABC, and later with Radio Today, until he and his family returned to their native Ireland towards the end of the century.

The broadcaster, Leslie Green, a great friend of Anne and Webster’s had gone to the UK for a holiday and sent recordings of his travels to the SABC to be broadcast on his Tea with Mr Green programmes while he was away. His wife had died in a car accident some years earlier when she was fetching their daughter Penny for the holidays from her boarding school. Penny survived the crash.

I had my singing lesson at 4.30pm after the programme was broadcast so Anne suggested that I should come in early and have tea with her and we could listen to the programmes together. He visited Anne’s great friend, Babs Wilson-Hill (Marie Thompson) and did an interview with her. He said that she had one of the most beautiful gardens in England.

Not long after his illness Anne and Webster (as themselves) shot a short scene in an Afrikaans film called Lord Oom Piet. In the film they sang Ah leave me not to pine from The Pirates of Penzance at a garden party, hosted by the new Afrikaans “lord” of the title, Jamie Uys. During their singing the lord, attired incongruously in a kilt, was attacked by a swarm of bees – or was it mosquitoes? The duet could not be completed as the lord squealed, rudely interrupting the singing, eventually flinging himself into a stream of water to relieve the stings -or the itch. Ruth and I saw the film when it was released at the end of 1962, and we despaired that Anne and Webster, two international stars, had chosen to make such an appearance in the film.

Singing in “Lord Oom Piet” (1962)

Singing in “Lord Oom Piet” (1962)At the end of 1962 Webster sang in Elijah and Messiah at the Port Elizabeth Oratorio Festival. Two older women in the SABC choir were constantly making disparaging remarks about the quality of his singing to Ruth and me, no doubt enjoying our discomfiture and hurt at their comments. Despite the fact that the music critic for the Eastern Province Herald wrote that he had sung “with superb artistry” in Elijah, I was distressed when none of his arias were played in the national SABC broadcast of excerpts from the Festival. The two women triumphantly cited this as proof that he was long past his vocal best.

Sylvia Sullivan and grand daughter.

Sylvia Sullivan and grand daughter.Bottom: Jean Campbell (later Collen) 1965

Jean Campbell later Collen (1965)

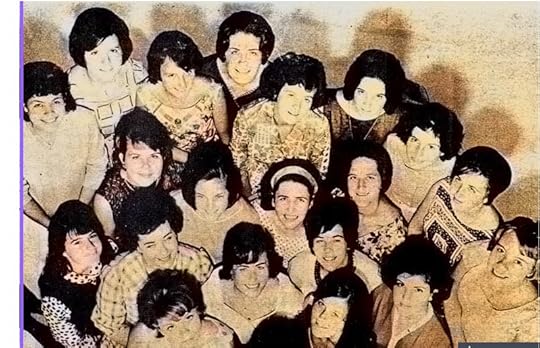

Jean Campbell later Collen (1965)Sylvia Sullivan Choristers. Jean is wearing a hairband. The photo includes the late Margaret Masterton, Gillian Viljoen, the late Belinda Bozzoli, Bridget Anderson, Mary Dreyer, Mary and Gretchen Hofmeyr, Sheila Prior and others.

The Sylvia Sullivan Choristers (1964). __ATA.cmd.push(function() { __ATA.initDynamicSlot({ id: 'atatags-26942-6068ad11105ca', location: 120, formFactor: '001', label: { text: 'Advertisements', }, creative: { reportAd: { text: 'Report this ad', }, privacySettings: { text: 'Privacy', onClick: function() { window.__tcfapi && window.__tcfapi( 'showUi' ); }, } } }); });

The Sylvia Sullivan Choristers (1964). __ATA.cmd.push(function() { __ATA.initDynamicSlot({ id: 'atatags-26942-6068ad11105ca', location: 120, formFactor: '001', label: { text: 'Advertisements', }, creative: { reportAd: { text: 'Report this ad', }, privacySettings: { text: 'Privacy', onClick: function() { window.__tcfapi && window.__tcfapi( 'showUi' ); }, } } }); });