Rebecca Lochlann on Flawed Heroines

I cannot identify with Lara Croft, (at all) Elektra, Yu Shu-lien, or the myriad other superwomen gracing many books and movies today. To me they are enticing but unrealistic, unattainable. They are almost as bad, in their way, as the Catholic Mary. What mortal woman-of-faith can live up to such spotless virtue (as defined by men?)

I cannot identify with Lara Croft, (at all) Elektra, Yu Shu-lien, or the myriad other superwomen gracing many books and movies today. To me they are enticing but unrealistic, unattainable. They are almost as bad, in their way, as the Catholic Mary. What mortal woman-of-faith can live up to such spotless virtue (as defined by men?)

Let's take Lara Croft. Not only is she completely pure of heart, she is stronger, bolder, more courageous and wiser than any man, anywhere. To top things off, (ha ha) she has gigantic (Freudian) boobs. In the first Tomb Raider movie, Lara uses a familiar karate move (one outstretched leg and foot) to strike a statue that comes to life and attacks her. Any normal human attempting this would find him or herself with a broken leg. The statue is made of solid rock, after all. Not Lara. She actually hurts the statue. The solid rock statue. Then she outruns a four-legged beast-like stone statue without even getting breathless. Later, faced with a choice between doing the "right" thing and doing what she longs to do, she weeps but does the right thing. Of course. There really are no surprises in the Tomb Raider movies. Lara does exactly what you would expect, all the time. Yawn.

In the second Tomb Raider movie, Lara makes a huge issue about how she "needs" Terry Sheridan. She "cannot" accomplish her mission without him. She gets him released from a high-security prison, then, the very first time he is required to make a decision, she refuses to listen to his advice. "We're going to do it this way," she states, and takes off on her motor scooter. Why was he even in this movie? She obviously did not need him so badly, after all. (She was "bold" while he was cautious. Poor, weak, man.)

Another movie that bothered me, although not so blatantly, was King Arthur. Here we have Guinevere, (Keira Knightley), a "warrior babe in face-paint," to quote the Amazon.com editorial review. It's like they tried to make her believable then at some point forgot their goal. The historical Guinevere might have actually been a warrior. Her fighting skills were not a problem for me, neither was her courage. Where I got lost? When she goes into battle in a tiny leather bikini, while her male compatriots are in full body armor. Really?

Now I love fantasy. I love Return of the King, Pan's Labyrinth, V for Vendetta, Ever After, 300, and Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within, all of which contain strong, intelligent, courageous women.

One of my all time favorite movie lines is "I am no man," coldly uttered by Eowyn just before she kills the Nazgul witch-king. This character is allowed to feel and act like a woman, and also fight like a real warrior, trained from childhood, would fight. She is completely believable.

I love strong, intelligent, courageous female characters, and I know for a fact that women, real and fictional, can be believable and strong, intelligent and courageous. They cannot be both believable and invincible. Besides the fact that such a concept is boring.

Ancient Great Britain offers up three women who, though foggy, have managed to not disappear completely from history:

Aife: Queen of Alba, said to be the most famous woman warrior of the Celtic heroic age.

Scathach: One of the greatest warriors and teacher of warriors. Some believe her legend proves there were women's military academies among the Celts.

The renowned Boudica, a historical figure if ever there was one.

More can be read about these women in several books, one of which is: The Encyclopedia of Amazons: Women Warriors from Antiquity to the Modern Era, by Jessica Amanda Salmonson.

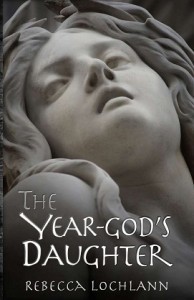

Current stories seem inclined to portray women as flawless, lacking even the perfectly normal "flaw" of not having as much physical strength as males. For Aridela, I wanted to create a protagonist who is strong, yes, but real and believable. I wanted to show how she acquires her strength, rather than simply shoving her out there already formed, as if by magic.

Child of privilege, daughter to the Queen of Crete, she has never known want or suffering. She has never experienced betrayal, humiliation, subterfuge or fear. Ten years old at the book's outset, Aridela is an indulged, sheltered princess. Adventurous, bold, and charismatic, Aridela is inherently ready, yet profoundly unprepared, to take the throne of Crete. The people adore her, her mother dotes on her; she impresses even the hard-nosed royal counselors. Like many of Crete's citizens, Aridela reveres beauty and beautiful things. She doesn't realize how shallow she is, because most around her are the same. The reader might be excused for thinking this child will grow up to be a spoiled, unlikeable woman, emphasis on "spoiled." Naturally, I wanted more for her.

Child of privilege, daughter to the Queen of Crete, she has never known want or suffering. She has never experienced betrayal, humiliation, subterfuge or fear. Ten years old at the book's outset, Aridela is an indulged, sheltered princess. Adventurous, bold, and charismatic, Aridela is inherently ready, yet profoundly unprepared, to take the throne of Crete. The people adore her, her mother dotes on her; she impresses even the hard-nosed royal counselors. Like many of Crete's citizens, Aridela reveres beauty and beautiful things. She doesn't realize how shallow she is, because most around her are the same. The reader might be excused for thinking this child will grow up to be a spoiled, unlikeable woman, emphasis on "spoiled." Naturally, I wanted more for her.

When Aridela meets and crushes on Menoetius, it's easy to understand why. He's a gorgeous, charming, seventeen year old foreigner with a delightful accent. What ten-year-old girl wouldn't fall for a guy like that? But he goes home and Aridela grows up. Now she hankers after another youth—no surprise that the object of her affection is a dazzling, celebrated bull leaper. It's when the warriors of the mainland converge upon Crete, determined to win the Games and become the next bull-king, that real challenges begin chewing away her comfort zone. Chrysaleon, the arrogant prince of Mycenae, introduces Aridela to passion. Again, it's easy to see what draws her: he's good looking and a prince. It takes her awhile to realize the guard he's brought with him is none other than her first love, Menoetius, but a profoundly different Menoetius than the boy she knew. No longer beautiful, he is the first challenge Divine Athene sets in her path. How will she deal with this angry, wounded man? She has no experience with the kind of pain he's suffered. Harpalycus, another mainland prince, introduces her to cruelty and shame. Harpalycus is Aridela's first exposure to humiliation, to fear, to a sense of weakness. He and the other mainland competitors lay bare the encroaching danger of the world outside her safe island paradise.

Aridela, a coddled princess, faces challenges that will either destroy her or incorporate the necessary components needed by all rulers from antiquity to the present: humility, caution, empathy, and compassion. Immortal Athene takes her child into the blackest, deepest pit where life no longer holds value. From that place, Aridela will survive and recover, honed by adversity, or she will become what her oppressors want. Either way, she will be very different from the child who brazenly entered the ring and joyously danced with a wild bull.

I often wonder why is there this need to portray women in the current fashion: invincible, superhuman strength, wise beyond logic, bold beyond reason, unassailable in mental purity? Perhaps because there is a sense that women want to break free of their past, where they have been so openly subjugated. I am only guessing. But if that is the case, is this attempt any more helpful to women than the previous notion (or expectation) that they were chaste, virtuous, pure, untouched, innocent, flighty, silly, and weak? "Creatures," (as they have often been labeled, as in not quite human) who must be protected, guided, and controlled?

For myself, I feel that portraying women as "superwomen" is just another manipulation, the same as when we were expected to be pure, selfless, and silly. Why can't we just be human, real, appreciated for all the wonderful qualities we offer, that have from the beginning made this world a better place?

I want the women in my books to achieve great things under their own mind-power, as real women must do.

Rebecca fell in love with the stories and myths of the ancient Greeks and wrote her first story at a very early age, due in part to the wonderful children's book, "D'Aulaires' Book of Greek Myths." She honed the craft of writing alongside formal education, marriage, and child rearing. Concurrent with building the series, she owned and operated a successful writing/editing company, helping authors prepare their work for publication and providing hundreds of articles on demand for marketing use and teaching seminars.

Rebecca fell in love with the stories and myths of the ancient Greeks and wrote her first story at a very early age, due in part to the wonderful children's book, "D'Aulaires' Book of Greek Myths." She honed the craft of writing alongside formal education, marriage, and child rearing. Concurrent with building the series, she owned and operated a successful writing/editing company, helping authors prepare their work for publication and providing hundreds of articles on demand for marketing use and teaching seminars.

"The Child of the Erinyes" is mythic historical fiction that begins in the Bronze Age and winds up in the near future.

Writing Influences? Patricia A. McKillip, Margaret Atwood, Anita Diamant, Peter S. Beagle, Anne Rice, and Yevgeny Zamyatin, to name a few.

It took about fifteen years to research the Bronze Age segments of the series, and encompassed rare historical documents, mythology, archaeology, ancient writing, ancient religions, and volcanology. For Rebecca, a rather obsessed historian, the research, the struggle for perfection, never ends.

"The Year-god's Daughter" is her first novel: Book One of "The Child of the Erinyes" Series. "The Thinara King" is scheduled for release in April, 2012. All of Rebecca's books will be published in paperback and eBook forms.

Though she cannot remember actually living in the Bronze Age, the Middle Ages, the Victorian era, and so on, she believes in the ability to find a way through the labyrinth of time, and that deities will sometimes speak to us in dreams and visions, gently prompting us to tell their forgotten stories.

Who knows? It could make a difference.

The Year-god's Daughter is available in paperback and eBook formats. The sequel, The Thenara King, is set for release in April 2012. (I'm very excited about this.) Ms. Lochlann is a member of Historical Fiction eBook and Past Times Books, both excellent sources for Historical Fiction of the highest quality. Check them out! You can also follow her on Twitter and Facebook. Visit Rebecca's website to learn more about her and her work.

newest »

newest »

Ha ha ha. I am trying...

Ha ha ha. I am trying...