Book Review: The Gulag Archipelago by Aleksandr I. Solzhenitsyn: Part Two: “Perpetual Motion,” Chapter Four, “From Island to Island”

And so we’re here, at the end of Part Two of Russian intellectual Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s most known work. Befitting his status as a total legend, Solzhenitsyn has taken us through, in these first two parts, a historical and sometimes circuitous route to answering the burning question most people have upon cracking open his story: What’s it like in the camps?

We’ve talked about the Soviet secret police’s arrest tactics and interrogation methods. We’ve learned about what it’s like in jail. We’ve been given a rather extensive survey of the history of the Soviet legal system, including the infamous Article 58. We’ve been given an overview of many, many landmark Soviet legal cases. We’ve delved into the psychology of prisoners waiting to be transported to the Gulag. And that was just in Part One.

In Part Two, Solzhenitsyn has taken us maddeningly, excruciatingly, through all the ways that prisoners were transported and stored on the way to the camps, explaining the usage of his term “Gulag Archipelago” with the metaphor of ships (modes of transportation) and ports (temporary transit prisons) Perhaps he went into too much detail. Perhaps he does not go into enough. But if merely getting there is this torturous, this laborious, this coldly and blandly sadistic, then what’s it like in the camps?

Here, at the end of Part Two of Five, and the last part in this particular volume based upon how the publisher decided to divide it up, we . . . still don’t really get a peek into life in the camps. No, Solzhenitsyn instead illuminates for us one final mode of prisoner transportation, one that he himself experienced:

And zeks [prisoners] are also moved from island to island of the Archipelago simply in solitary skiffs. This is called special convoy. It is the most unconstrained mode of transport. It can hardly be distinguished from free travel. Only a few prisoners are delivered in this way. I, in my own career as a prisoner, made three such journeys.

The special convoy is assigned on orders from high officials.

To prisoners used to the abuse and inhumane treatment of the Stolypin cars or Black Marias or red cattle cars, the special convoy is a godsend, though a cruel one. Traveling with one, maybe two or three guards, the prisoner is not bound, not beaten, not even verbally abused, though he knows if he makes a break for it he will be shot on sight. Instead, the prisoner may actually travel by normal train like a normal person and told to act as naturally as possible. This is harder than it sounds, for the prisoner knows that the ruse is up once they reach their final destination. Such is the strange vagary of totalitarianism: the appearance of normalcy must be presented even though everyone knows there is no recourse for the most barbaric cruelties inflicted upon its subjects.

Solzhenitsyn’s life changed when, in camp (though he doesn’t give any more details about the camp) he was told he was to be transported by direct order of Minister of Internal Affairs Sergei Kruglov himself.

But why?

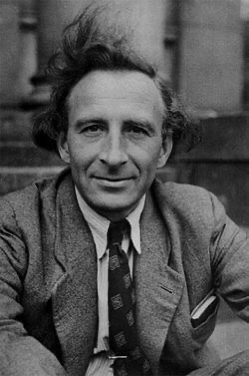

Soviet Minister of Internal Affairs Sergei Nikiforovich Kruglov (1946-1956)

Soviet Minister of Internal Affairs Sergei Nikiforovich Kruglov (1946-1956)Solzhenitsyn posits his theory. When given his customary Gulag registration card, upon which, among other vital information, the zeks were to write their occupation, Solzhenitsyn “frowned and filled in ‘nuclear physicist.'”

He was not, nor had he ever been, a nuclear physicist.

As an aside: why are we, those of us alive and still relatively free in the twenty-first century, so interested in what it’s like in prison and labor camps? Is it because all we hear about in 20th century history classes and books and documentaries is the horror of prison camps? Is it because many of us expect to be in one someday soon?

This point is this, though: The Gulag is more than just the camps.

Solzhenitsyn says he soon forgot about the card, until he was pulled aside on Kruglov’s direct order some time later. Prisoners knew that there were only a few possible meanings of this: a new stretch of prison . . . or being released. But one thing they all knew is that once Kruglov had his eye on you, there was no escape.

He then recounts a mysterious, unconfirmed rumor among prisoners at the camps:

There was a vague, unverified legend, unconfirmed by anybody, that you might nevertheless hear in camp: that somewhere in this Archipelago were tiny paradise islands. No one had seen them. No one had been there. Whoever had, kept silent about them and never let on. On those islands, they said, flowed rivers of milk and honey, and eggs and sour cream were the least of what they fed you; things were neat and clean, they said, and it was always warm, and the only work was mental work–and all of it super-supersecret.

And so it was that i got to those paradise islands myself (in convict lingo they are called “sharashkas”) and spent half my sentence on them. It’s to them i owe my survival, for I would never have lived out my whole term in the camps. And it’s to them i owe the fact that I am writing this investigation, even though I have not allowed them any place in this book. (I have already written a novel about them.) And it was from one to another of those islands, from the first to the second, and from the second to the third, that I was transported on a special-convoy basis: two jailers and I.

The experience was surreal. Solzhenitsyn likens it to being a would of the dead hovering above the living and just observing but not participating. “Act naturally . . .” How could anyone act naturally in such a circumstance? Solzhenitsyn shares a humorous anecdote of sitting in a separate car from his guards, though they kept their eye on him, and speaking with another traveler who joined him–Solzhenitsyn even drinks a proffered beer (he was told to “act naturally,” after all) . . . only to deduce later that his companion, too, was a member of the secret police. The Gulag was truly a small world after all.

“After spending a few hours among free people,” Solzhenitsyn notes, “here is what I feel: My lips are mute; there is no place for me among them; my hands are tied here. I want free speech! I want to go back to my native land! I want to go home to the Archipelago!” Such is the psychological toll being tormented by the state has wrought.

And where did Solzhenitsyn end up first? Why, back in Butyrki Prison in Moscow!

Butyrki Prison, Moscow

Butyrki Prison, MoscowIt was like coming home. Not only were the conditions far, far better than those in the ships and the ports of the Archipelago, not only was there more food, more warmth, and books, and sleep–oh, precious sleep. Importantly, Solzhenitsyn found some wonderful company among the prisoners–though he had to fudge his knowledge of nuclear physics, he befriended many intelligent people who sparked wonderful discussions about science and philosophy, including the famous biologist Nikolai Timofeyev-Ressovsky, the President of the Scientific and Technical Society of Cell 75. Professor Timofeyev-Ressovsky had the misfortune of studying and conducting research in Germany before the outbreak of the Second World War.

Nikolai Timofeyev-Ressovsky

Nikolai Timofeyev-RessovskyAlong with his colleague Sergei Tsarapkin, Timofeyev-Ressovsky naively thought that Soviet soldiers would let him continue his research in Russia. However, when the soldiers set about ransacking his laboratory, Timofeyev-Ressovsky objected, which naturally made him an enemy. So into the Butyrki he went!

Solzhenitsyn reports these as happy times, proving that there is a silver lining everywhere:

No, even before the war, when I was studying at two higher educational institutions at the same time and earning my way by tutoring, and striving to write too, even then I had not experienced such full, such heart-rending, such completely filled days, as I did in Cell 75 that summer.

It wasn’t all easy, though. Displaying the black humor that has gotten Russians through many a hardship, Solzhenitsyn explains a little in-joke among the zeks:

And on the bowls will be stamped (so we shouldn’t make off with them in the prisoner transport) the mark “Bu-Tyur”–for Butyskraya Tyurma, Butyrki Prison. The “BuTyur ” Health Resort, as we mocked it last time. A health resort, incidentally, very little known to the paunchy bigwigs who want so badly to lose weight. They drag their stomachs to Kislovodsk, and go out for long hikes on prescribed trails, do push-ups, and sweat for a whole month just to lose four to six pounds. And there in the “BuTyur” Health Resort, right near them, anyone of them could lose seventeen or eighteen pounds just like that, in one week, without doing any exercises at all.

This is a tried and true method. It has never failed.

Solzhenitsyn was later moved into the second story of a church that was converted into a prison–the Soviet state never let anything go to waste, after all–waiting to be moved to where Comrade Kruglov would send him. He encounters a Romanian spy and several other interesting folks, but most of all he is struck by the attitude of those prisoners of the younger generation. For starters, they were not immediately dismissive of religion, and more than a few were believers themselves. What these younger prisoners weren’t was believes in the Soviet system. Solzhenitsyn notices that their alienation and lack of hope actually gave them fatalistic clarity. They don’t need to fight for the Motherland and try to build a good life, have it stripped from them, and then see the rot and evil inherent in the system.

These young people thrown into the Gulag meat-grinder never had anything to begin with. They see the system the way it is from the get-go, and realize that what had been taken from them is what they need to return to some semblance of goodness and decency. The parallels between American Millennials–analogies to Solzhenitsyn’s generation–and Zoomers–these young ones Solzhenitsyn encountered in the church cell–is chilling:

Our generation would return [from the war]–having turned in its weapons, jingling its heroes’ medals, proudly telling its combat stories. And our younger brothers would only look at us contemptuously: Oh, you stupid dolts!

***

Though it comes early in the chapter, I find these words of wisdom a good way to close out our survey of The Gulag Archipelago, Vol. 1 (Parts One and Two). It’s taken me a long time to read, digest, analyze, and write-up each chapter of this landmark work, but I’ve found it very educational and thought-provoking. I hope you’ve gotten some sort of value out of it too, and we’ll see you in Volume 2!

Do not pursue what is illusory–property and position: all that is gained at the expense of your nerves decade after decade, and is confiscated in one fell night. Live with a steady superiority over life–don’t be afraid of misfortune, and do not yearn after happiness; it is, after all, the same: the bitter doesn’t last forever, and the sweet never fills the cup to overflowing. It is enough if you don’t freeze in the cold and if thirst and hunger don’t claw at your insides. If your back isn’t broken, if your feet can walk, if both arms can bend, if both eyes see, and if both ears hear, then whom would you envy? And why? Our envy of others devours us most of all. Rub your eyes and purify your heart–and prize above all else in the world those who love you and who wish you well. Do not hurt them or scold them, and never part from any of them in anger; after all, you simply do not know: it might be your last act before your arrest, and that will be how you are imprinted in their memory!

Takeaways:

There is no logic or reason in a dictatorship. There is friend/enemy. That’s it. That’s all that matters. Learn this or go mad.Freedom takes practice, and human beings learn to fit their container. If you’re in jail long enough, that becomes your frame of reference, your normal, after time. Opporessors know this and use this.Oppressive, soulless states will use people like widgets, like tools. This can inure to one’s personal benefit, but it’s illusory.Generations view things differently because they have different life experiences. All generations need to work together and understand one another, and the older must look after the younger or else.