Rethinking running records

In the past I was a strong proponent of running records. I used them every day as a first and second grade classroom teacher, and as an online educator I’ve often promoted their use.

I felt that a running record – a visual representation of a child’s reading – was a wonderful tool to see exactly where readers were struggling and to know where to take them next.

A traditional running record

A traditional running recordBut now that I’ve adopted a more structured approach to early literacy (after my research into how the brain learns to read), I believe we must reconsider running records.

Running records are still popular todayMany teachers are required to administer running records, and many choose them all on their own (I did!).

They use the results to group children for reading instruction and to guide students to a particular level when they read independently.

Should we still be using running records?

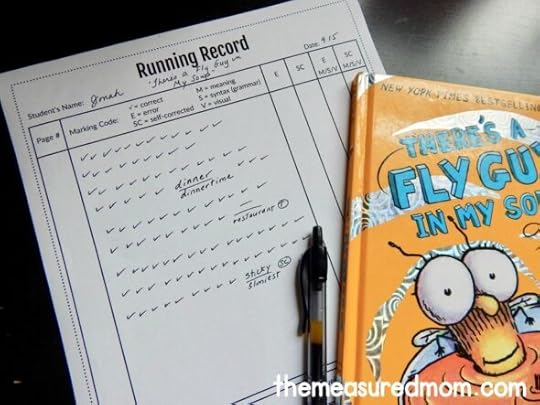

Why I didn’t want to let go of running recordsAs a teacher, my favorite thing about running records is that they were quick and efficient. I could do them anywhere!And I did! I used them daily during conferences when I listened to individual readers. I used these informal running records to get a quick visual of my students’ errors.

I could also get a quick picture of how fluently my students were reading. And when they answered questions about the text, I could jot down notes about their comprehension on the back of the page.

Why we should reconsider running recordsIt does not give me pleasure to reconsider running records. I LOVED them.

However.

The biggest issue that I see is the way that running records require us to analyze “miscues” (errors) using the three-cueing system: meaning, syntax, and visual cues.

The idea with running records is that we are to note whether students made a meaning, grammar, or phonics error when reading.

The problem with this is that we now know that the brain learns to read by connecting phonemes (sounds) to graphemes (letters), not by using meaning or grammar cues to solve words.

(See podcast episode 37: How the brain learns to read)

If we are giving kids text with words whose sound-spelling patterns we’ve taught them, they won’t need to use pictures or context to solve words.

And we shouldn’t want them to.

Novice readers need to focus on matching sounds to letters and sequences of letters so that they can literally identify words and begin to store then in their brain for instantaneous retrieval, i.e. “map” them orthographically.

Breaking the Code

Do you see the issue? If you are teaching kids to sound out words using the phonics patterns you’ve explicitly taught, then that is what you should be measuring … not whether they are using context or other clues to solve words.

Traditional running records don’t tell us what we truly need to knowIf your school teaches reading using a phonics program, measuring progress with this tool is a total mismatch.

Jocelyn Seamer Education

What you really need to know is how proficient your readers are with phonemic awareness. A running record can’t tell you that. (Try the free PAST Test instead.)

What you really need to know is how solid your students’ phonics skills are. A traditional running record only has columns for meaning, syntax, and visual cues … not a place to analyze specific decoding errors. Use an assessment that comes with your phonics program, or this free one.

What you really need to know is whether or not your learner is reading at an appropriate rate. While reading rate doesn’t determine whether or not a child is a strong reader, a low rate can be an indicator of other issues. Many teachers use DIBELS.

Should we throw running records away?Even if that were my recommendation, you may not have a choice. Let’s discuss how to make running records into a useful tool.

First, make sure that the text you use matches what would be used in a solid instructional approach.

Instead of assessing student reading on leveled text that requires the use of pictures and context clues, assess the reading of a quality decodable text that features sound-spelling correspondences you’ve taught.

Instead of marking whether students attended to meaning, syntax, or visual cues, note specifically what decoding errors were made.

Is the reader solving CVC words fluently? Or is s/he mixing up short o and short u?

Is the reader struggling with specific high frequency words that could use extra attention?

Is the reader using what you’ve taught about solving multi-syllable words?

Make other helpful notes in the margin.

Is the reader jumping to the pictures first when solving words? This is valuable information, because you’ll want to correct it. Make a note.

Is the reader sounding out words incorrectly and not self-correcting, even when it doesn’t make sense? Make a note.

Is the reader neglecting to read with attention to punctuation marks? Make a note.

Can the reader answer your questions after the reading? Make a note.

Final thoughtsIf you have the time, I believe that sitting and listening to a child read one-on-one is invaluable.

While I no longer believe that the traditional running record is a good assessment tool, an adjusted running record form could be useful.

You just need to know what text to use, what to listen for, and how to use your observations to address concerns.

Quotes in this post

Jocelyn Seamer Education – Time to Break up with Running RecordsBreaking the Code – Why Running Records and Leveled Readers Don’t Mix with PhonicsThe post Rethinking running records appeared first on The Measured Mom.

Anna Geiger's Blog

- Anna Geiger's profile

- 1 follower