Book Review: The Gulag Archipelago by Aleksandr I. Solzhenitsyn: Part Two: “Perpetual Motion,” Chapter Three, “The Slave Caravans”

It was painful to travel in a Stolypin, unbearable in a Black Maria, and the transit prison would soon wear you down–and it might just be better to skip the whole lot and go straight to camp in the red cattle cars.

Reading The Gulag Archipelago can be an exhausting experience. There are only so many ways one can describe the brutality with which the Soviet state transported prisoners and how they were treated on various modes of transportation en route to the Gulag. One can only read so much about the abuse heaped upon this wretched lot without wanting to put the book down. This is not because Solzhenitsyn is a bad writer, or the information he conveys is not important. Far from it! Solzhenitsyn is such a good writer, in fact, that one wants to keep reading despite the grim subject matter. It’s a catch-22 if there ever was one.

It also got me thinking, as I read about this last and most torturous way of transporting actual human beings whom the baleful eye of the Soviet government had fallen upon, packed into these red carts like human cattle, what I would do in this situation. Would I have the guts to stand up to my oppressors and risk a beating, or worse? Or would I meekly accept my lot and surrender to the jackboots and the billy clubs, the privation and the cold, the slop that passes for foot, the shit and piss flooding the train car floor from the overflowing privy bucket as I lay on the cold wooden planks amidst the human waste, packed tightly with other forms of human waste?

I don’t know. God willing, I will never know, though with the way things are going in the Land of the Free here, I may just get my chance.

As an aside, from this excellent article about Soviet deportations, I learned that many of the freight cars Stalin used to ship prisoners to the Gulag were acquired from the Lend-Lease program with the United States. Freedom and democracy!

In this chapter, Solzhenitsyn pieces together what the experience in one of these cattle cars was like–all too vividly, in fact–and what it was like at some of the preliminary work camps. Carts left for the Kolyma–Siberia–nearly every day, populating the Gulag with its unfortunate settlers. Entire populations were moved this way–Volga Germans to Kazakhstan, for example. The thing was, while Stolypin cars had to go to actual campsites, the red cattle cars might deposit prisoners into the middle of nowhere and expect them to build their own camp or start work on some construction project immediately

Of course, these cars had to be prepared . . . “[b]ut not in the sense some readers might expect”:

[T]hat the coal or lime it carried before it carried people had to be swept out and the car cleaned–that isn’t always done. Nor in the sense that it needs to be calked and have a stove installed if it is winter.

Sounds lovely.

The interiors were bare-boned. Sometimes prisoners had to lay on the freezing cold floor while entire sections of new railroad were being build to these God-forsaken parts of the wilderness: In one instance, “[i]n winter the zeks [prisoners] lay on the icy, snowy floor and weren’t even given any hot food, because the train could make it all the way through this section in less than a day.”

Could you survive eighteen to twenty hours of this without going mad or having your spirit broken? I don’t know if I could.

Loading the prisoners presented another challenge for the Soviet authorities. As we saw in the first two chapters in this part of the book, there were two overriding considerations: (1) “to conceal the loading from ordinary citizens,” and (2) “to terrorize the prisoners.”

The loading of this human cattle was therefore done at night. But the women, wives and mothers and lovers of the prisoners, somehow found out and milled about, trying to provide some succor to their loved ones–political prisoners, mind you, and not the hardened criminals (the “thieves”) given free reign by the prison wardens as a part of this campaign of terror. They were marched at night in the cold at gunpoint, sometimes in the blaze of searchlights, their possessions stripped and given to their jailers. After all, it was “simple justice to take all the good things they [the prisoners] possess . . . [as] enemies of the people for the use of its sons.”

Asset forfeiture! Does this sound familiar?

Again, these were political prisoners. Better to be a murderer or a robber or a rapist in Soviet Russia. As long as you were a member of the correct class and not a class traitor, you were still a true member of the Soviet state, not these disgusting 58s.

I know I belabor the point, but this sounds far too familiar for comfort.

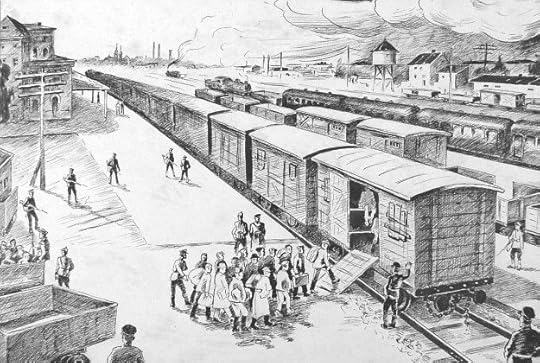

A depiction of the Estonian deportation.

A depiction of the Estonian deportation.The conditions in the train were abhorrent, of course: cold, packed tightly, limited rations, thieves who had already taken the best spots and who were allowed to forcibly steal what possessions hadn’t been taken by the so-called trustees as booty (Solzhenitsyn recounts one instance where a hated Estonian’s gold teeth were extracted by the thieves with a poker).

Food distribution was another form of terror: sometimes the gruel was slopped into the same pails used to transport coal. Often there weren’t enough spoons or bowls for everyone. And scariest of all, even more frightening than these physical privations, was the psychological terror of not knowing your final destination. At least in the Stolypins, you had an idea of which transit prison you were going to and a rough idea of how long it would ideally take to get there. Prisoners in the cattle cars were afforded no such luxury. This led to the crazed idea that things would be better at the camp, if the train would only get there!

The ride was not necessarily over once the train stopped. Sometimes prisoners had to make an overland trek through the snowy wilderness to their final destination because there was no other way. So with dogs barking and guards shouting and beating stragglers, prisoners marched to where they prayed things would be easier.

Sometimes there wasn’t even a camp.

Solzhenitsyn goes on. Sometimes these journeys on foot lasted days, weeks. Other times prisoners had to take steamships, which presented their own horrors. And then you got to camp, where at least the promise of hot food and maybe a bath, or even a little space, presented itself.

Shut your eyes, reader. Do you hear the thundering of wheels? Those are the Stolypin cars rolling on and on. Those are the red cows rolling. Every minute of the day. And every day of the year. And can you hear the water gurgling–those are the prisoners’ barges moving on and on. And the motors of the Black Marias roar. They are arresting someone all the time, cramming him in somewhere, moving him about. And what is that hum you hear? The overcrowded cells of the transit prisons. And that cry? The complaints of those who have been plundered, raped, beaten to within an inch of their lives.

We have reviewed and considered all the methods of delivering prisoners, and we have found that they are all . . . worse. We have examined the transit prisons, but we have not found any that were good. And even the last human hope that there is something better ahead, that it will be better in camp, is a false hope.

In camp it will be . . . worse.

Takeaways:

Political enemies of the state are treated far worse than actual criminals.If the state deems you an enemy, you are no longer considered human and will no longer be treated as such. The only distinction that matters is friend/enemy.The terror is the point.Entire ethnic groups were considered political enemies. Sound familiar?How anyone can retain a fondness for the Soviet Union can only be explained by demonic influence.Things can always get worse.